Major spoilers ahead, so consider yourself warned. First off, I'll acknowledge that Sicario looks great, has an inventive, tension-inducing musical score, and has some action set pieces that are really, really well choreographed. That's where the good news ends. Sicario is also the most badly-plotted film I've seen in a very long time. Some of the Roger Moore James Bond films have more logical and believable plots. The few reviews I've read of Sicario (all laudatory) have apparently been blind to this titanic flaw, apparently fooled by the film's muscular realism and energy. This is a film that skips merrily from one bit of plot inanity to another without catching its breath. And that's not the worst thing about Sicario.

The first scene in the film has FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) leading a raid on a suburban house in Arizona that we assume is a drug den or something of that ilk. She kills one of the men guarding the house and then finds that the ranch bungalow's walls are stuffed with bodies, victims, presumably, of a Mexican drug cartel. Why the cartel would go to all this bother rather than burying people in the surrounding empty desert isn't explained, nor why a cartel henchman would fire at Kate when it's a clear he has no chance to avoid arrest. I'll give the scriptwriter a pass on this one, as the real purpose of the scene is to show us that Kate isn't reluctant to shoot people and that the cartel does some really bad things. Shortly after this raid, Kate is asked to volunteer for a special task force that's targeting the head of one of the Mexican cartels. The task force is led by Matt (Josh Brolin), who commands a small force of ex-Navy Seals(?), and one scary dude named Alejandro played by Benicio del Toro.

From here on, the plot get worse. The film's main action sequence involves the transfer of a prisoner from a jail in Juarez to the American side of the border just a few miles away. It's great cinema, but it has no internal logic. Why ferry the prisoner out of Juarez in a convoy of SUVs (they're ambushed, naturally) when a chopper ride would be easier? Even more ridiculously, the convoy has a cleared road and Mexican police escorts from the border to the prison, but then when they get back to the border the convoy vehicles have to line up with all the other daytrippers going to the U.S. They couldn't get a special lane to themselves for the return journey? Was U.S. Customs afraid the Seals might bring back some undeclared booze? An ambush takes place that's notable for continuing the cinematic trope of henchman being more than willing to give up their lives in a lost cause.

The film's big plot reveal comes past the halfway mark when Matt tells Kate that the only reason she was asked to volunteer for the group is so the CIA could operate on U.S. soil. Evidently the law dictates that the CIA can't operate domestically unless it's allied with a law enforcement agency. So Kate's role is purely symbolic. And why the CIA, you ask? Because they want to wipe out the Mexican cartels and replace them with the Medellin cartel from Colombia. According to Matt, things were better for everyone when only one cartel was in charge of things. All I can say is that a CIA plot this stupid belongs in a Steven Seagal movie.

And that brings me to the film's biggest problem: Kate isn't just a footnote to the CIA's operation, she's a footnote in the film. Take Kate out of the film and absolutely nothing about the story changes. The CIA operation goes as planned, the same people end up dead, and the same final result is achieved. Kate is entirely superfluous. If that wasn't bad enough, the film also goes whole hog on the sexism and misogyny. Kate might be brave, good with guns, and able to kill ruthlessly when necessary, but that's only the script paying lip service to the idea of gender equality. What the story has her mostly doing is fulfilling the traditional role of women in issue-oriented action films; she acts as the scold and nag, the voice of conscience. Poor Emily Blunt has to spend the entirety of the film whining and complaining about "following procedure", and generally being the finger-wagging schoolmarm/mom/wife while Josh Brolin and Benicio del Toro get to act cool, look cool, and talk cool. The film then doubles down on the sexism with some bonus misogyny; to wit, Kate is held down and choked by a corrupt cop (and rescued by Alejandro); shot in her bulletproof vest by Alejandro; and then knocked to the ground and pinned there like an unruly puppy or disobedient child by Matt. What all three scenes have in common is that she's assaulted by these men after she dares to interfere with or criticize their respective schemes. And the film's penultimate scene has Kate crying when Alejandro forces her to sign an incriminating document, because, well, girls always cry under pressure, don't they?

With a 93% approval rating on RottenTomatoes.com, it's clear that Sicario's technical excellence and sharp action sequences have acted as a smokescreen to a more critical examination of its script. Take away Denis Villeneuve's slick direction and Roger Deakins' wonderful cinematography and you have a film that feels like a sequel to Lone Wolf McQuade, a Chuck Norris vehicle from the 1980s. The plot is an unholy mess, its sexual politics are reprehensible, and the politics of the drug trade are ignored in favour of random scenes that reassure we northerners that Mexico is just as big a hellhole as we imagine it to be.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Friday, October 16, 2015

Book Review: Brodeck (2007) by Philippe Claudel and Eat Him if You Like (2009) by Jean Teule

The French know a thing or two about mobs. In fact, they pretty much invented the modern mob back in 1789, and since then they've stayed in game shape with major mob events in 1830 (the July Revolution), 1870 (the Commune), 1968 (the May riots) and, most recently, the 2005 riots in the country's banlieues. It comes as no surprise, then, that a couple of French authors should write novels that dissect the psychology of mob activity.

Brodeck is set in an alternate reality Europe that mostly resembles Austria or Germany in the 1930s. The title character lives in a small village high in the mountains where he works as a low-level government functionary. As the novel begins, Brodeck is summoned to the town's inn where he learns that almost all the men in the village have murdered a man know only as the Outsider. The men ask Brodeck to write a report on what happened in the town that led to the killing of the Outsider. The narrative now skips back and forth between Brodeck's investigation and flashbacks to his grim and tortured life before arriving in the village.

Claudel's novel is a slightly surreal, fable-like meditation on all the ways people can find to despise and persecute those unlike themselves. The Outsider who ends up being killed is emphatically more symbol (a saint? a holy fool? God?) than a character. He's odd and eccentric, mostly silent, and it feels like he's dropped into the village after an adventure in one of Italo Calvino's fabulist novels. The slightly whimsical nature of the Outsider is offset by Brodeck's back story, which is a litany of some of the 20th century's showcase atrocities--concentrations camps, pogroms, persecution, and total war. Claudel's novel veers towards the didactic from time to time, but he more than makes up for it with some wonderful world-building. His alternative Europe is artfully done, and his detailed descriptions of the village and its citizens are beautifully realized.

Eat Him if You Want is the nasty, brutish and short take on mob behavior. It's actually an almost blow for blow recounting of a true event in French history that took place in 1870. The setting is a small village during a summer fair. Word has come from the north that the war with Prussia, only a few weeks old, is going badly for France, which is simply more bad news on top of the drought which is gripping the region. A local haute bourgeoisie man, Alain de Moneys, comes to the fair to conduct some business and a few members of a semi-drunken crowd think (wrongly) that they hear him say something pro-Prussian. What starts as anger among a few drunks metastasizes into an orgy of violence directed against Moneys. For over two hours he's beaten and tortured in ways only French peasants could dream up, culminating in his being burnt alive and, yes, partially eaten. His death was the definition of senseless, and many of his attackers were later arrested and executed or sent to penal colonies.

No gruesome detail is spared in Teule's novella, but the blood and horror is leavened with black humor and a tone of ironic detachment that makes the savagery and madness on display all the more affecting. Teule doesn't ask us to draw lessons from this historical incident, or even try to understand more than the simplest of motivations behind the attack. He simply shows in clinical detail how a mass of people can turn into not just killers, but brutal architects of pain.The worst thing about the crime is that it reveals how imaginatively cruel the average person can be and how willing they are to put their sickening fantasies into action.

Both novels are in the Premier League of harrowing, and not to be read on a crowded subway train where people are likely to be testy and react badly if you bump into them while your nose is buried in one of these books. And kudos to Gallic Books for bringing out Eat Him if You Like and a raft of other French novels in translation which I'm slowly working my through. Allons-y!

Brodeck is set in an alternate reality Europe that mostly resembles Austria or Germany in the 1930s. The title character lives in a small village high in the mountains where he works as a low-level government functionary. As the novel begins, Brodeck is summoned to the town's inn where he learns that almost all the men in the village have murdered a man know only as the Outsider. The men ask Brodeck to write a report on what happened in the town that led to the killing of the Outsider. The narrative now skips back and forth between Brodeck's investigation and flashbacks to his grim and tortured life before arriving in the village.

Claudel's novel is a slightly surreal, fable-like meditation on all the ways people can find to despise and persecute those unlike themselves. The Outsider who ends up being killed is emphatically more symbol (a saint? a holy fool? God?) than a character. He's odd and eccentric, mostly silent, and it feels like he's dropped into the village after an adventure in one of Italo Calvino's fabulist novels. The slightly whimsical nature of the Outsider is offset by Brodeck's back story, which is a litany of some of the 20th century's showcase atrocities--concentrations camps, pogroms, persecution, and total war. Claudel's novel veers towards the didactic from time to time, but he more than makes up for it with some wonderful world-building. His alternative Europe is artfully done, and his detailed descriptions of the village and its citizens are beautifully realized.

Eat Him if You Want is the nasty, brutish and short take on mob behavior. It's actually an almost blow for blow recounting of a true event in French history that took place in 1870. The setting is a small village during a summer fair. Word has come from the north that the war with Prussia, only a few weeks old, is going badly for France, which is simply more bad news on top of the drought which is gripping the region. A local haute bourgeoisie man, Alain de Moneys, comes to the fair to conduct some business and a few members of a semi-drunken crowd think (wrongly) that they hear him say something pro-Prussian. What starts as anger among a few drunks metastasizes into an orgy of violence directed against Moneys. For over two hours he's beaten and tortured in ways only French peasants could dream up, culminating in his being burnt alive and, yes, partially eaten. His death was the definition of senseless, and many of his attackers were later arrested and executed or sent to penal colonies.

No gruesome detail is spared in Teule's novella, but the blood and horror is leavened with black humor and a tone of ironic detachment that makes the savagery and madness on display all the more affecting. Teule doesn't ask us to draw lessons from this historical incident, or even try to understand more than the simplest of motivations behind the attack. He simply shows in clinical detail how a mass of people can turn into not just killers, but brutal architects of pain.The worst thing about the crime is that it reveals how imaginatively cruel the average person can be and how willing they are to put their sickening fantasies into action.

Both novels are in the Premier League of harrowing, and not to be read on a crowded subway train where people are likely to be testy and react badly if you bump into them while your nose is buried in one of these books. And kudos to Gallic Books for bringing out Eat Him if You Like and a raft of other French novels in translation which I'm slowly working my through. Allons-y!

Tuesday, October 6, 2015

Film Review: Black Mass (2015)

If Black Mass was a pizza it would only have one topping; if it was a car it would be a base model Toyota Corolla; and if it was a day of the week it would be Wednesday. Black Mass is the blandest gangster film that's ever been made. It's not dull, it's not bad, but it leaves absolutely no impression on your cinematic palate. The film tells the true story of Whitey Bulger, a small-time Boston gangster who became a big-time gangster in the 1980s thanks to the tacit support of the FBI, who were relying on Bulger to give them intel on Boston's sole mafia family. Bulger gave them very little real info, but the protection and tips he got from the FBI (and one agent in particular) let him rule Boston's underworld for more than a decade.

Where Black Mass goes wrong is in concentrating on the FBI's involvement with Bulger. It's true that this is what makes the Bulger case of news interest, but it has very little cinematic value. The appeal of gangster films lies in the gangster lifestyle. Goodfellas is a masterpiece because it shows the visceral appeal of life in the mob, especially how that life was for street-level hoods. The Godfather also shows us a gangster lifestyle, albeit one that's built around an operatic plot and an acidic attack on the myth of the American Dream. Black Mass goes through the motions of showing Bulger whacking some people, beating up others, and generally being feral and threatening, but we don't get any clear idea of what his criminal empire was built on. His downfall began with his involvement with jai alai games in Florida. The film does a terrible job of telling us what jai alai is and how Bulger profits from it. And Bulger's underlings are barely developed. We register their presence, but they might as well be nameless extras for all the impact they have. Instead of describing the gangster life, the film gives us scene after scene of guys sitting around tables in homes and offices doing nothing but talk, talk, talk. At the halfway point in the film I began to feel I was watching some kind of dramatic re-enactment show on the History Channel.

The actors all turn in capable performances, but they're held back by a script that lacks wit and energy. All the salient points in Bulger's career are covered, which is fine for an essay, but not so charming in a film. And one odd thing I noticed is that either the actors or the scriptwriter have no ear for swearing. Everyone curses up a storm, but it always sounds awkward and forced. Goodfellas evidently holds the record for sweariest film of all time but in that film the expletives felt natural and almost poetic. In Black Mass the curses are there to enliven otherwise dreary dialogue sequences.

Where Black Mass goes wrong is in concentrating on the FBI's involvement with Bulger. It's true that this is what makes the Bulger case of news interest, but it has very little cinematic value. The appeal of gangster films lies in the gangster lifestyle. Goodfellas is a masterpiece because it shows the visceral appeal of life in the mob, especially how that life was for street-level hoods. The Godfather also shows us a gangster lifestyle, albeit one that's built around an operatic plot and an acidic attack on the myth of the American Dream. Black Mass goes through the motions of showing Bulger whacking some people, beating up others, and generally being feral and threatening, but we don't get any clear idea of what his criminal empire was built on. His downfall began with his involvement with jai alai games in Florida. The film does a terrible job of telling us what jai alai is and how Bulger profits from it. And Bulger's underlings are barely developed. We register their presence, but they might as well be nameless extras for all the impact they have. Instead of describing the gangster life, the film gives us scene after scene of guys sitting around tables in homes and offices doing nothing but talk, talk, talk. At the halfway point in the film I began to feel I was watching some kind of dramatic re-enactment show on the History Channel.

The actors all turn in capable performances, but they're held back by a script that lacks wit and energy. All the salient points in Bulger's career are covered, which is fine for an essay, but not so charming in a film. And one odd thing I noticed is that either the actors or the scriptwriter have no ear for swearing. Everyone curses up a storm, but it always sounds awkward and forced. Goodfellas evidently holds the record for sweariest film of all time but in that film the expletives felt natural and almost poetic. In Black Mass the curses are there to enliven otherwise dreary dialogue sequences.

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

Film Review: Figures in a Landscape (1970)

One of the great things about filmmaking in the late 1960s and early '70s is that no one knew what they were doing. The studio system in Hollywood was collapsing into bankruptcy, formerly reliable film genres such as musicals and westerns were dying on the vine, and laxer censorship meant whole new avenues of creative expression were opened up. All this meant that producers, who were as much in the dark as anyone, were willing to take a chance on projects that were non-traditional; in fact, some producers were probably hunting for oddball films to make in the hope that they'd catch the next wave that would carry them out of the film production wilderness. And that's probably how Figures in a Landscape got made.

Figures is not a good film, but it's eccentric ambitions make it very watchable. The two stars are Robert Shaw and Malcolm McDowell, the director was Joseph Losey, and Shaw also wrote the screenplay, which is based on a novel by Barry England. The minimalist story has two men, Mac and Ansell, on the run from the authorities in an unnamed country. We don't know their crime, their guilt or innocence, or the political character of the country they're in. They're pursued by an ominous black helicopter that seems able to find them at will and direct ground forces against them. The landscape of the title is arid and mountainous (it was shot in Spain), and might be a country in southern Europe or even Latin America. The men's goal is a snowy mountain range that marks the border with another country.

Harold Pinter's name isn't on the credits, but it might as well be. Shaw and Losey had both worked with Pinter on multiple occasions and his influence is very clear. This is an action film that's also a bickering, claustrophobic, absurdist drama, with the helicopter and its faceless pilot becoming a symbol of...well, whatever you want, I guess. Mac and Ansell dislike each other from the beginning and are reluctant allies. They spend most of their time quarreling or telling redundant stories about their lives back in Britain, and like many Pinter characters they attach enormous importance to the most trivial details of their lives. As a Pinter play, it's not a very good one. The dialogue isn't sharp or witty or off-kilter enough, and Mac (Shaw) gets far too much of the dialogue. Ansell (McDowell) spends most of the film looking scared and not much else.

What saves this film are its cinematic elements. The cinematography and use of locations is excellent, as is the musical score by the underrated Richard Rodney Bennett. What's most surprising about the film is its action scenes. Early in the film Mac and Ansell are buzzed by the chopper in a sequence that looks like it was very dangerous to film for both the actors and the pilot. Another sequence set in a cane field is equally dynamic, and, all in all, it's possible to enjoy this film as the most stripped-down action/escape film ever made. I have a feeling that was the intention all along; to try and do an action-adventure film without any of the traditional back story and character development that encumber most films in this genre. The attempt to add some intellectual cachet to the story through the use of stylistic references to Pinter and Samuel Beckett is wholly unsuccessful. Although the producer really missed an opportunity to call the film Running From Godot. Now that's marketing.

Saturday, September 12, 2015

Book Review: Blood Meridian (1985) by Cormac McCarthy

The first Cormac McCarthy novel I read was Cities of the Plain, and it's fair to say that I found it comprehensively bad. "But no!" people said. "That's the wrong one to start with. You should have read Blood Meridian!" There's a small group of writers I've read over the years that have elicited the same sort of response from friends and acquaintances. I tell someone I've read novel x by Ernest Hemingway/Graham Greene/Thomas Pynchon and not been impressed, and I'm then immediately told I read the wrong one--I should have read For Whom the Bell Tolls/Brighton Rock/Gravity's Rainbow. There seems to be a category of authors who are guaranteed to disappoint the reader unless you know how to tiptoe through his or her literary minefield.

Long story short, I gave McCarthy another chance. It was a qualified failure. Blood Meridian is widely regarded as his best novel, and is frequently mentioned as one of the great novels of modern American literature. I'll start with the good. Unlike Cities of the Plain and its dry, tone deaf prose, this novel features some superb descriptive writing. The novel follows a group of rapacious gunslingers called the Glanton gang on an odyssey through Texas, Mexico and the American Southwest as they hunt Apaches for a bounty on their scalps. McCarthy's descriptions of the land, the weather, and the hardscrabble towns the gang pass through are magnificent. His masterful way with metaphors and similes is astounding, and the novel can be enjoyed (partially) as an epic prose poem about the Old West.

Unfortunately, great description does not a novel make. It helps to have compelling characters, and McCarthy can't create characters if his life depended on it. All his cowboys comes from a big bin marked "Western extra type B: laconic." The Glanton crew are an undifferentiated mass of slow-talking cowpokes who sound as though they're in a western film rather than a western novel. The only exception is Judge Holden, who is given paragraph after paragraph of opaque, overripe, rambling dialogue about life and death and fate. It's pretty silly stuff, and feels like a misguided attempt to ape some of William Faulkner's characters, the ones who muse on existence and metaphysics while out on quail hunting trips. Holden is more symbol than man, and just in case the reader doesn't get this, McCarthy makes him exceedingly tall, completely hairless, white as a ghost, and exceptionally cruel. I'm surprised McCarthy stopped short of giving him a tattoo reading "Evil Incarnate." Holden is to be regarded, I'm guessing, as either a cruel god, a playful demon, or Death itself. He's so overdrawn, however, that he ends up in the same camp as cartoon horrors such as Freddy Kruger, Hannibal Lecter, and the better-quality Bond villains.

The plot is somewhere between thin and threadbare. The gang roams across the west killing just about every man, woman, child and animal they encounter. In-between massacres, atrocities and isolated killings, the boys get drunk, shoot up towns, and rob and rape. It's all a bit lather, rinse, repeat. If you were to stop reading it after about a hundred pages the only thing of interest you'd be missing is more prose poetry. The violence is unrelenting and, in the end, tedious. It doesn't add to our understanding of the barely-there characters, and the various bloody events read like scenes culled from McCarthy's favourite western films. In fact, one brief scene feels like a direct steal from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

The farther I got into Blood Meridian, the more I realized that Phillipp Meyer's 2013 novel The Son is a kind of rebuttal to McCarthy's book. Meyer's western novel tackles some of the same themes, even has an ultra-violent Holden-like character, but spreads itself over a much larger canvas with more imagination and skill, and, perhaps most strikingly, features native American and Mexican characters who aren't just cannon fodder for Yankee guns. And as it happens, I wouldn't recommend reading Meyer's first novel, American Rust (2009). It's the wrong one to start with.

Long story short, I gave McCarthy another chance. It was a qualified failure. Blood Meridian is widely regarded as his best novel, and is frequently mentioned as one of the great novels of modern American literature. I'll start with the good. Unlike Cities of the Plain and its dry, tone deaf prose, this novel features some superb descriptive writing. The novel follows a group of rapacious gunslingers called the Glanton gang on an odyssey through Texas, Mexico and the American Southwest as they hunt Apaches for a bounty on their scalps. McCarthy's descriptions of the land, the weather, and the hardscrabble towns the gang pass through are magnificent. His masterful way with metaphors and similes is astounding, and the novel can be enjoyed (partially) as an epic prose poem about the Old West.

Unfortunately, great description does not a novel make. It helps to have compelling characters, and McCarthy can't create characters if his life depended on it. All his cowboys comes from a big bin marked "Western extra type B: laconic." The Glanton crew are an undifferentiated mass of slow-talking cowpokes who sound as though they're in a western film rather than a western novel. The only exception is Judge Holden, who is given paragraph after paragraph of opaque, overripe, rambling dialogue about life and death and fate. It's pretty silly stuff, and feels like a misguided attempt to ape some of William Faulkner's characters, the ones who muse on existence and metaphysics while out on quail hunting trips. Holden is more symbol than man, and just in case the reader doesn't get this, McCarthy makes him exceedingly tall, completely hairless, white as a ghost, and exceptionally cruel. I'm surprised McCarthy stopped short of giving him a tattoo reading "Evil Incarnate." Holden is to be regarded, I'm guessing, as either a cruel god, a playful demon, or Death itself. He's so overdrawn, however, that he ends up in the same camp as cartoon horrors such as Freddy Kruger, Hannibal Lecter, and the better-quality Bond villains.

The plot is somewhere between thin and threadbare. The gang roams across the west killing just about every man, woman, child and animal they encounter. In-between massacres, atrocities and isolated killings, the boys get drunk, shoot up towns, and rob and rape. It's all a bit lather, rinse, repeat. If you were to stop reading it after about a hundred pages the only thing of interest you'd be missing is more prose poetry. The violence is unrelenting and, in the end, tedious. It doesn't add to our understanding of the barely-there characters, and the various bloody events read like scenes culled from McCarthy's favourite western films. In fact, one brief scene feels like a direct steal from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

The farther I got into Blood Meridian, the more I realized that Phillipp Meyer's 2013 novel The Son is a kind of rebuttal to McCarthy's book. Meyer's western novel tackles some of the same themes, even has an ultra-violent Holden-like character, but spreads itself over a much larger canvas with more imagination and skill, and, perhaps most strikingly, features native American and Mexican characters who aren't just cannon fodder for Yankee guns. And as it happens, I wouldn't recommend reading Meyer's first novel, American Rust (2009). It's the wrong one to start with.

Monday, September 7, 2015

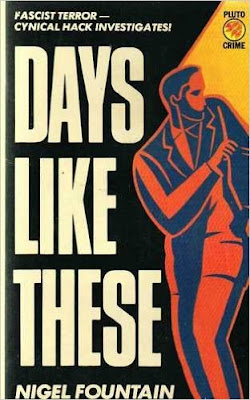

Book Review: Days Like These (1985) by Nigel Fountain

The left-wing thriller has always been a rare animal. Eric Ambler started the sub-genre in the late 1930s with novels like Journey Into Fear. After the war Ambler's enthusiasm for communists in the role of heroes cooled, but not his hatred of fascism and dictators. The vast majority of thrillers, if they have any political content at all, are usually right-wing or, more commonly, take a cynical, all sides are rotten and corrupt view of the world. The few writers who continued the leftist tradition (in English) included Julian Rathbone and John Fullerton. Rathbone eventually gave up thrillers and Fullerton (my review of This Green Land) is almost totally forgotten.

Days Like These is very much from the Ambler school of thriller writing. Ambler's protagonists are almost always middle-class Britons, politically naive, who find themselves caught up in conspiracies and plots that both baffle and frighten them. An Ambler hero has to muddle his way through danger, aided only by luck, pluck, and the timely intervention of a savvy leftist with a gun. The lead character in Days Like These is John Raven, an intermittently employed journalist in London who was once a committed lefty but is now content to drift around the edges of the movement. John is leading a quiet life of floating from odd job to pub to bedsit and back again, until he has the bad luck to buy some odd photographs and also witness the bombing of a politician's house. The two events are connected, and John is soon the focus of thugs and a nascent fascist conspiracy.

If the overall structure of the novel is Ambleresque, the tone and style owes more to Evelyn Waugh. This is as much a bleakly comic novel as it is a thriller, and Fountain takes great delight in describing the petty squabbles and bickering that constantly divides and sub-divides his characters on the left. The comic nature of the novel becomes even more apparent at the end when Raven becomes a hidden witness to a fascist conspiracy crumbling into internecine bloodletting. In fact, Raven ends up not having a much or any effect on the plot. He accidentally becomes aware of a right-wing conspiracy (it's a rather shambolic conspiracy) and spends the rest of the novel evading the bad guys until they eventually self-destruct. It's not a traditional thriller structure, but something about it reminded me of Evelyn Waugh's Scoop. Unlike Waugh, however, Fountain's sympathies are definitely on the left. His leftists may at times be absurdly idealistic, petty, doctrinaire and quick to anger, but they are not bloodthirsty or ignorant.

Fountain is an excellent writer. His descriptions of the demi-monde of left-wing London are richly detailed and quietly comic. Everyone seems to have one eye on the next deviation in political orthodoxy and the other on who's due to stand the next round. And London itself is presented as a seedy, frayed city of drab pubs, ratty apartments, and littered streets. This makes the novel sound bleak, but the vivacity of the characters and Raven's cynical, time-for-another-pint charm more than make up for the tatty surroundings. Days Like These isn't going to fit with most people's idea of a thriller, but excellent writing doesn't need to sit squarely in a genre box. My main problem with the book is that it's the only thriller Fountain wrote. If he does write another I'll gladly stand him several rounds in his favourite questionable pub.

Days Like These is very much from the Ambler school of thriller writing. Ambler's protagonists are almost always middle-class Britons, politically naive, who find themselves caught up in conspiracies and plots that both baffle and frighten them. An Ambler hero has to muddle his way through danger, aided only by luck, pluck, and the timely intervention of a savvy leftist with a gun. The lead character in Days Like These is John Raven, an intermittently employed journalist in London who was once a committed lefty but is now content to drift around the edges of the movement. John is leading a quiet life of floating from odd job to pub to bedsit and back again, until he has the bad luck to buy some odd photographs and also witness the bombing of a politician's house. The two events are connected, and John is soon the focus of thugs and a nascent fascist conspiracy.

If the overall structure of the novel is Ambleresque, the tone and style owes more to Evelyn Waugh. This is as much a bleakly comic novel as it is a thriller, and Fountain takes great delight in describing the petty squabbles and bickering that constantly divides and sub-divides his characters on the left. The comic nature of the novel becomes even more apparent at the end when Raven becomes a hidden witness to a fascist conspiracy crumbling into internecine bloodletting. In fact, Raven ends up not having a much or any effect on the plot. He accidentally becomes aware of a right-wing conspiracy (it's a rather shambolic conspiracy) and spends the rest of the novel evading the bad guys until they eventually self-destruct. It's not a traditional thriller structure, but something about it reminded me of Evelyn Waugh's Scoop. Unlike Waugh, however, Fountain's sympathies are definitely on the left. His leftists may at times be absurdly idealistic, petty, doctrinaire and quick to anger, but they are not bloodthirsty or ignorant.

Fountain is an excellent writer. His descriptions of the demi-monde of left-wing London are richly detailed and quietly comic. Everyone seems to have one eye on the next deviation in political orthodoxy and the other on who's due to stand the next round. And London itself is presented as a seedy, frayed city of drab pubs, ratty apartments, and littered streets. This makes the novel sound bleak, but the vivacity of the characters and Raven's cynical, time-for-another-pint charm more than make up for the tatty surroundings. Days Like These isn't going to fit with most people's idea of a thriller, but excellent writing doesn't need to sit squarely in a genre box. My main problem with the book is that it's the only thriller Fountain wrote. If he does write another I'll gladly stand him several rounds in his favourite questionable pub.

Sunday, September 6, 2015

Stephen Harper's Flock of Odd Birds

Like a harsh light casting long and dark shadows, the combination of a federal election campaign and Mike Duffy's fraud trial has thrown into sharp relief the strange group of characters that flit around PM Stephen Harper and the upper echelons of Conservative politics in Canada. This eccentric crew includes: Nigel Wright, Ray Novak, Guy Giorno, John Baird, James Moore, Jason Kenney, Jenni Byrne, Arthur Hamilton, and Patrick Brown.

Now, bear with me because I'm going to be practicing psychology without a licence for the duration of this blog post. What unites the aforementioned dramatis personae, aside from politics, is their sheer oddness. A kind of weirdness that was best described by Charles Portis in his brilliant comic novel Masters of Atlantis, about a ludicrous only-in-America cult:

Through a friend at the big Chicago marketing firm of Targeted Sales, Inc., he got his hands on a mailing list titled Odd Birds of Illinois and Indiana, which, by no means exhaustive, contained the names of some seven hundred men who ordered strange merchandise through the mail, went to court often, wrote letters to the editor, wore unusual headgear, kept rooms that were filled with rocks or old newspapers. In short, independent thinkers who might be more receptive to the Atlantean lore than the general run of men.

Yes, that pretty much describes the people circling in Harper's orbit, except that they aren't as harmless or humorous as Portis' creations. Reading through the bios and newspaper profiles of these assorted Conservatives leaves one with the clear impression that this bunch (including Harper) is made up entirely of social misfits, loners, psychopaths and religious fanatics. One thing they almost all have in common is that they attached themselves to conservative politics with limpet-like determination as teenagers. While the rest of us were out drinking, partying, chasing the opposite sex, or just goofing around in various nerdy ways, Harper's odd birds were canvassing for rightist candidates, campaigning for student president, and generally marking themselves out as people no one wanted to hang with. Call me a libertine, but there's something scary/sad/suspicious about a teen who embraces politics with steely determination to the exclusion of sex, drugs and rock 'n roll.

Harper's flock are determined loners. With the exception of Hamilton and Giorno, all of them are single. Patrick Brown, the new leader of Ontario's Progressive Conservatives and once an MP in Harper's government, has said that he hasn't "had much time for that". The "that" in question is a relationship. It's telling that Brown can't bring himself to use words like "marriage" or "girlfriend.", and as a Conservative it's too much to expect him to admit to wanting a boyfriend. It's slightly disturbing that so many of Harper's inner circle are unable or unwilling to form long-term relationships, although it's also possible that some of them, as rumor would have it, are deeply-closeted and simply don't want to upset Harper's socially-conservative base. Ray Novak, currently Harper's chief of staff, is the poster boy for social self-denial. He actually moved in with Harper and his family for four years and became a sort of uncle or brother to the Harper family.

As a substitute for personal, intimate relationships, this crew has opted for dog-like devotion to Harper and the cause of conservatism. Their bios are littered with references to their selfless, tireless, continuous efforts to promote and sustain the Conservative party and conservative causes. If they weren't working for the party directly they were laboring for right-wing advocacy groups or think tanks. None of them seem to have taken a breath of air in a non-political environment. The only break some of them take from political fanaticism is to indulge in some religious fanaticism. Wright and Giorno are staunch Catholics, and Hamilton and Harper are from the evangelical side of the spectrum. This religiosity wouldn't be remarkable for a random group of US politicians, but in Canada it gives them "odd bird" status.

Harper is notoriously uncomfortable around other people, even his own children, and this election campaign has seen him fence himself off from any kind of human contact that hasn't been thoroughly vetted. But this kind of anti-social activity pales next to Arthur Hamilton, who in an interview with the Globe and Mail basically said that the only thing that keeps his sociopathy in check are his fundamentalist Christian beliefs. And what's with the all the running? Wright gets up before dawn every morning, every morning, and runs 20km. Novak gets up at 5 a.m. to run, although his jogs are evidently shorter in length. These regimens smack more of self-flagellation than of fitness.

This leads me to the big question: why has Canadian conservatism attracted, or turned to, so many apparent head cases? The answer comes in a study done of incompetent military commanders done by psychologist Norman F. Dixon. He writes:

Incompetent commanders, it has been suggested, are often those who were attracted to the military because it promised gratification of certain neurotic needs. These include a reduction of anxiety regarding real or imagined lack of virility/potency/masculinity; defences against anal tendencies; boosts for sagging self-esteem; the discovering of loving mother-figures and strong father-figures; power, dominance and public acclaim; the finding of relatively powerless out-groups on to whom the individual can project those aspects of himself which he finds distasteful; and legitimate outlets for, and adequate control of, his own aggression.

Dixon is writing about military commanders, but his analysis applies equally well to many right wing politicians (who are almost always militarists as well) and especially to Harper & Co. Stephen and his covey of odd birds use conservatism, of both the political and religious variety, to assuage and hide some aspects of their personalities they'd rather not face. Self-esteem, or the lack of it, is at the root of what attracts this bunch to conservatism. Brown had a painful childhood stutter, Wright was adopted, Hamilton has a dark, violent secret in his past, and several others appear to have spent their lives terrified of coming out. It's an absolute Las Vegas buffet of self-esteem issues.

Over the last several decades conservatism has become more militaristic, xenophobic, intolerant of cultural differences, doctrinaire, religious, scornful of economic underclasses, and hostile to criticism and analysis. These qualities give strength to people whose perceive their own identity as being weak or uncertain. Today's conservatism trades in simplistic certainties backed with macho bluster, religious pieties, martial rhetoric, and facile, pitiless economic logic. It's a movement that gives strength and purpose and confidence to those who can't find these qualities in themselves.

Related post:

What Makes a Conservative Conservative?

Now, bear with me because I'm going to be practicing psychology without a licence for the duration of this blog post. What unites the aforementioned dramatis personae, aside from politics, is their sheer oddness. A kind of weirdness that was best described by Charles Portis in his brilliant comic novel Masters of Atlantis, about a ludicrous only-in-America cult:

Through a friend at the big Chicago marketing firm of Targeted Sales, Inc., he got his hands on a mailing list titled Odd Birds of Illinois and Indiana, which, by no means exhaustive, contained the names of some seven hundred men who ordered strange merchandise through the mail, went to court often, wrote letters to the editor, wore unusual headgear, kept rooms that were filled with rocks or old newspapers. In short, independent thinkers who might be more receptive to the Atlantean lore than the general run of men.

Yes, that pretty much describes the people circling in Harper's orbit, except that they aren't as harmless or humorous as Portis' creations. Reading through the bios and newspaper profiles of these assorted Conservatives leaves one with the clear impression that this bunch (including Harper) is made up entirely of social misfits, loners, psychopaths and religious fanatics. One thing they almost all have in common is that they attached themselves to conservative politics with limpet-like determination as teenagers. While the rest of us were out drinking, partying, chasing the opposite sex, or just goofing around in various nerdy ways, Harper's odd birds were canvassing for rightist candidates, campaigning for student president, and generally marking themselves out as people no one wanted to hang with. Call me a libertine, but there's something scary/sad/suspicious about a teen who embraces politics with steely determination to the exclusion of sex, drugs and rock 'n roll.

Harper's flock are determined loners. With the exception of Hamilton and Giorno, all of them are single. Patrick Brown, the new leader of Ontario's Progressive Conservatives and once an MP in Harper's government, has said that he hasn't "had much time for that". The "that" in question is a relationship. It's telling that Brown can't bring himself to use words like "marriage" or "girlfriend.", and as a Conservative it's too much to expect him to admit to wanting a boyfriend. It's slightly disturbing that so many of Harper's inner circle are unable or unwilling to form long-term relationships, although it's also possible that some of them, as rumor would have it, are deeply-closeted and simply don't want to upset Harper's socially-conservative base. Ray Novak, currently Harper's chief of staff, is the poster boy for social self-denial. He actually moved in with Harper and his family for four years and became a sort of uncle or brother to the Harper family.

As a substitute for personal, intimate relationships, this crew has opted for dog-like devotion to Harper and the cause of conservatism. Their bios are littered with references to their selfless, tireless, continuous efforts to promote and sustain the Conservative party and conservative causes. If they weren't working for the party directly they were laboring for right-wing advocacy groups or think tanks. None of them seem to have taken a breath of air in a non-political environment. The only break some of them take from political fanaticism is to indulge in some religious fanaticism. Wright and Giorno are staunch Catholics, and Hamilton and Harper are from the evangelical side of the spectrum. This religiosity wouldn't be remarkable for a random group of US politicians, but in Canada it gives them "odd bird" status.

Harper is notoriously uncomfortable around other people, even his own children, and this election campaign has seen him fence himself off from any kind of human contact that hasn't been thoroughly vetted. But this kind of anti-social activity pales next to Arthur Hamilton, who in an interview with the Globe and Mail basically said that the only thing that keeps his sociopathy in check are his fundamentalist Christian beliefs. And what's with the all the running? Wright gets up before dawn every morning, every morning, and runs 20km. Novak gets up at 5 a.m. to run, although his jogs are evidently shorter in length. These regimens smack more of self-flagellation than of fitness.

This leads me to the big question: why has Canadian conservatism attracted, or turned to, so many apparent head cases? The answer comes in a study done of incompetent military commanders done by psychologist Norman F. Dixon. He writes:

Incompetent commanders, it has been suggested, are often those who were attracted to the military because it promised gratification of certain neurotic needs. These include a reduction of anxiety regarding real or imagined lack of virility/potency/masculinity; defences against anal tendencies; boosts for sagging self-esteem; the discovering of loving mother-figures and strong father-figures; power, dominance and public acclaim; the finding of relatively powerless out-groups on to whom the individual can project those aspects of himself which he finds distasteful; and legitimate outlets for, and adequate control of, his own aggression.

Dixon is writing about military commanders, but his analysis applies equally well to many right wing politicians (who are almost always militarists as well) and especially to Harper & Co. Stephen and his covey of odd birds use conservatism, of both the political and religious variety, to assuage and hide some aspects of their personalities they'd rather not face. Self-esteem, or the lack of it, is at the root of what attracts this bunch to conservatism. Brown had a painful childhood stutter, Wright was adopted, Hamilton has a dark, violent secret in his past, and several others appear to have spent their lives terrified of coming out. It's an absolute Las Vegas buffet of self-esteem issues.

Over the last several decades conservatism has become more militaristic, xenophobic, intolerant of cultural differences, doctrinaire, religious, scornful of economic underclasses, and hostile to criticism and analysis. These qualities give strength to people whose perceive their own identity as being weak or uncertain. Today's conservatism trades in simplistic certainties backed with macho bluster, religious pieties, martial rhetoric, and facile, pitiless economic logic. It's a movement that gives strength and purpose and confidence to those who can't find these qualities in themselves.

Related post:

What Makes a Conservative Conservative?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)