The Great Migration is the term used to describe the movement of black Americans away from the Deep South starting during the First World War and continuing into the 1950s and '60s. The estimated six million blacks who fled the South were leaving behind abject poverty, violent racism and Jim Crow laws. This novel follows three brothers from Kentucky who go north in 1919 to work in the steel mills of Pennsylvania. The Moss brothers, Big Mat, Melody and Chinatown, flee their farm (they're sharecroppers) after Mat is cheated out of receiving a new mule by a white overseer. Mat, who is a walking pillar of anger at the best of times, strikes down the overseer and kills him.

The brothers immediately get work in the mills and find themselves living in a radically different world. Their fellow workers are almost entirely migrants, although from Ireland and eastern Europe, and they're free, mostly, of the racism that was part of the air the brothers breathed in Kentucky. There's even a black supervisor in charge of white workers at the mill. Although the brothers are making more money than they've ever dreamed of, they haven't landed in paradise. The work is difficult and dangerous, and they soon realize that black workers are viewed with suspicion because they're often brought in as strikebreakers. Sure enough, a strike action does take place and the brothers find themselves caught in the middle.

William Attaway, who was black, only wrote two novels, and this one, his last, should be better known. It was probably inspired by The Grapes of Wrath, the story of America's great white migration, but unlike Steinbeck, Attaway takes a harsher look at his main characters. The Moss brothers are not overly sympathetic. Chinatown in feckless and lazy, Mat is a violent brute, and Melody is weak and indecisive. It's clear, however, that their personalities have been forged in the racism and economic structures of the South in the same way that raw material is forged into steel in the North. The brothers are ill-equipped for the relative freedoms of the North. They drag their psychological peonage with them, and when Mat gets a chance to be become a police deputy and strikebreaker, he leaps at the opportunity to be an empowered black man exerting authority over whites. It doesn't turn out well for him.

The novel also has a very clear-eyed view of class politics. The tragedy of the novel is that the workers at the steel mill can't see that the mill owners are using race as a wedge to divide them. Whites see the blacks as scabs, and the blacks are seduced into this role by the lure of unheard of wages (compared to sharecropping) and by their ingrained habit of obeying white authority. None of the workers, white or black, can see the commonality of their struggle.

Attaway has a real flair in describing working-class life. The mill is a place of danger, yet awe-inspiring in its violence and ferocity. The ramshackle town that surrounds the mills is vividly described, with no attempt to avoid showing the brutal nature of some of its inhabitants. Attaway was clearly sympathetic to the suffering of the downtrodden, but never shows any inclination to sanitize their lives; in fact, this is probably why the novel did not do well on its release. It would have been too raw for most of the white, middle-class reading public, and even supporters of the working classes might have been daunted by its portrayal of people on the bottom of the economic ladder. The Grapes of Wrath was a much more palatable option in the field of proletarian literature.

Tuesday, April 25, 2017

Thursday, March 30, 2017

Henchman Politics

In contemporary politics it's the henchmen, underlings, flunkies and idiot sons who are now in charge. Villainous characters have often reached the top in politics, but they at least maintained a facade of sober competence, even respectability. In Thunderball Spectre conducted business behind (literally) an organization to help refugees. In the non-fictional world, Richard Nixon was as bad as they come but he was always composed in his public appearances and utterances. And today? Politicians such as Rodrigo Duterte, Recep Erdogan, and Nigel Farage behave like characters who would be spectacularly killed off in the second act of most action films. And then we have Donald Trump, the Fredo Corleone of U.S. presidents presiding over a posse of henchmen so transparently villainous they belong in a Steven Seagal film.

Political supervillains are still around (Putin being the obvious example), but, as a sign of their cunning, they've mostly left the arena of elected politicians and do their plotting through think tanks, media organizations and PACs. The Koch brothers, Rupert Murdoch, Sheldon Adelson, Robert Mercer and various other multi-billionaires put their assorted henchmen in power and happily watch them emasculate every level of government. Henchmen politicians, through their bombast, bullshit, arrogance, stupidity, cruelty and ignorance are more effective than a death ray in eroding the foundations of good governance and democracy.

Another characteristic of henchmen is psychopathy, and it certainly looks like we've entered the age of the political psychopath. Henchmen politicians can't even pretend to be interested in improving the welfare of the average citizen; in fact, they proudly and consciously expend most of their energy on making things worse for almost everyone. Climate change, income inequality, the rights of minorities, and active and potential military conflicts around the world are the most pressing issues of the day. The Trump administration is actively making things worse in all these areas.

The reason the Murdochs and Kochs of the world have created and funded this situation is that they, like generations of plutocrats before them, realize that democracy is fundamentally inimical to capitalism. A healthy democracy, even one as ramshackle and antiquarian as the U.S., works to better the lives of all its citizens by regulating and limiting the power of capitalists. The hallmark of a non-democratic state is the concentration of wealth and power in a very, very few hands. And such is the goal of today's power brokers. What sets them apart from previous generations of capitalists is that their anti-democratic ambitions are more open, less subtle, and are stage-managed by a supporting cast of smirking fools and pious sadists--henchmen to the core. A socialist James Bond is clearly needed, but I'm not holding my breath.

Monday, March 20, 2017

Film Review: Kong: Skull Island (2017)

This is a poorly-made movie and that immediately makes it the best of the Kong/Godzilla reboots that have bellowed and crashed their way into multiplexes over the last decade and a bit. I include Godzilla in the mix because whether the star monster is covered in scales or fur, the films they're in all follow the same playbook. Where previous iterations have gone wrong is in trying to be conventionally good films--you know, the kind with properly developed characters, plausible dialogue, and believable human relationships. That's not what monster movies (or "kaiju" films if you want to get excessively nerdy) are supposed to be about. The appeal of these films is in watching outsized critters kick ass. That's it. No one wants anything more. The original Toho films stuck to this formula and surrounded the smackdown sequences with preposterous dialogue, barely-there plots, and stock characters. Kong: Skull Island is a return to those roots.

The smashing, the roaring, and the screaming of terrified humans starts early and rarely lets up. The effects are fine, and kids, the real and traditional audience for this kind of film, should have a joyous time at the theatre. The rest of us can marvel at how little in the way of directorial competence and script writing ability one gets for a budget of $200m. There are far too many supporting actors (none of whom are introduced properly), all the dialogue is flat, and most of the actors seem unsure of what tone to adopt. Samuel L. Jackson takes his part very, very seriously, John C. Reilly is looking around for Will Ferrell to riff with, Brie Larson seems distracted, and Tom Hiddleston gives us the poshest ex-SAS mercenary ever--instead of a gun I was expecting him to be armed with a Fortnum & Mason's picnic hamper.

As shambolic as most of the film is, it at least delivers lots of visual thrills in a reasonable running time, something that none of the recent monster megafauna movies have managed to do. Peter Jackson's King Kong was farcical, Pacific Rim was tedious and visually muddy, and, the worst of all, Godzilla (2014) was perversely determined to not show off its titular hero. So let's hope the Kong: Skull Island sequels are all as enthusiastically dumb.

The smashing, the roaring, and the screaming of terrified humans starts early and rarely lets up. The effects are fine, and kids, the real and traditional audience for this kind of film, should have a joyous time at the theatre. The rest of us can marvel at how little in the way of directorial competence and script writing ability one gets for a budget of $200m. There are far too many supporting actors (none of whom are introduced properly), all the dialogue is flat, and most of the actors seem unsure of what tone to adopt. Samuel L. Jackson takes his part very, very seriously, John C. Reilly is looking around for Will Ferrell to riff with, Brie Larson seems distracted, and Tom Hiddleston gives us the poshest ex-SAS mercenary ever--instead of a gun I was expecting him to be armed with a Fortnum & Mason's picnic hamper.

As shambolic as most of the film is, it at least delivers lots of visual thrills in a reasonable running time, something that none of the recent monster megafauna movies have managed to do. Peter Jackson's King Kong was farcical, Pacific Rim was tedious and visually muddy, and, the worst of all, Godzilla (2014) was perversely determined to not show off its titular hero. So let's hope the Kong: Skull Island sequels are all as enthusiastically dumb.

Sunday, March 12, 2017

Bring Back the Red Menace!

|

| If you enjoy paid vacations, free healthcare and a pension, you might want to thank this guy. |

In David Sasson's 1998 book One Hundred Years of Socialism, he makes the case that the presence of communist states and strong communist parties in places like France and Italy effectively emboldened socialist parties in their demands for worker's rights and strong social welfare policies. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the western political world, particularly in Europe, was terrified by the possibility of communist parties coming to power. The fear of communism forced or encouraged parties of the left and centre, and even some on the right, to move their politics further to the left as a strategy to draw the teeth of the red menace. The idea was simple: if the working classes were well, or at least adequately, provided with living wages, legal protection for unions, free healthcare, pensions, low or free university tuition, and unemployment benefits, then they would be less likely to turn to communist parties. Socialist parties in particular benefited from the red menace. The perceived threat of communism allowed them to build strong social welfare policies, nationalize various industries, and establish high tax rates for the wealthy. These policies were palatable to the middle classes and above because the communist alternative was far more alarming.

The appeal of communism and the influence of the USSR began to decline with the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and accelerated with their invasion of Afghanistan eleven years later. The failure of communist economies to provide a consumerist lifestyle equal to that of the west was yet another, and equally important factor, in its decline. With the election of Thatcher in 1979 and Reagan in 1980, the conservative counter-revolution against the social welfare state was underway. When the USSR shifted to a more western and liberal outlook under Gorbachev, and then broke apart, in '91, conservatives were quick to claim that this was the inevitable triumph of capitalism.

The end of communism produced two swift, and parallel, responses. One was the rightward shift of leftist parties, most notably Britain's Labour Party, which morphed into so-called New Labour. These new socialist parties embraced capitalist concepts like globalization, deregulation, lower corporate taxes, and privatization once they no longer had to contend with competing communist parties. The other immediate response came from capitalists and rightists who became solidly triumphalist in their outlook. For them, capitalism had been proven to be the only viable political/economic reality. Parties of the left offered minimal or non-existent resistance to this view, and from '91 onwards voters in the developed world were left with a choice between different flavours of capitalism. Terms like "working class" and "underclass" disappeared from the lexicon of leftist parties to be replaced by the more aspirational "middle class," a group everyone was trying to get in or stay in.

The triumphalism of capitalism since 1991 has led to what I'd call Manichean capitalism--any public policy which adds to a company's bottom line is incontrovertibly good, while one which hinders or reduces profitability is bad in an almost existential sense. We've now reached a stage where being opposed to capitalism is seen in many quarters as being deviant or immoral or criminal. The angry reactions from the right to the Occupy Wall Street protests in 2011 are an illustration of this. More recently, the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the British Labour party produced a vituperative reaction in British right wing circles because Corbyn was, by their definition, an extreme leftist. By the political standards of the 1960s and '70s Corbyn was your average leftist, but in 2015 he was a "loony" lefty, to use the parlance of Brit tabloids. The prospect of someone of that ilk becoming PM was enough to send the capitalist establishment into a fury of denunciations, smear jobs, and dark warnings about the future of Britain.

Now that the major political parties in most developed countries have tacitly agreed that capitalism, preferably the Manichean variety, is the bedrock upon which all public policy is built, how do they differentiate between themselves come election day? Through nationalism, sidebar issues, scandal-mongering and identity politics. Political policy and campaigning built around the concept of national programs that benefit the majority have gone by the wayside, replaced by bickering over local and regional interests, and venomous arguments over people who are supposedly getting more than their fair share. In Britain, the tabloids work tirelessly to demonize migrants, so-called "benefits cheats", and a dozen other fringe and minority groups, all of whom, according to the tabs, are parasitical in one way or another. The last US election was built on scapegoating minority groups.

Whether it's a government of the left or right, the developed world is in a rush to abandon the activist social welfare policies that characterized governments in the post-war era. Ethno-nationalism, the most abstract, meaningless and vicious of political concepts, is what has often replaced it, Communism (in theory if not always in practice) acted as a counterweight to this political philosophy by taking a rational, analytical and critical look at the relationship between labour and capital. And perhaps more importantly, communism kept alive the concept of actions taken for the collective good. What we're left with now is irrational invective, jingoism and hate-mongering. Communism was never a panacea, but it's role in retarding the growth of Manichean capitalism has largely been overlooked.

Monday, November 28, 2016

Trilogies of Terror!

If you're an aspiring novelist who wants to work in the mystery, SF or fantasy field, you'd better roll your up sleeves and get busy because no one's going to take you seriously unless you've got at least a trio of linked novels to your credit. Part of my job at the library consists of selecting books to send to shut-ins, and it's always a nuisance wrangling a trilogy for delivery because volume ones are inevitably checked out for months. Volume threes are always readily available, and that says something about the literary staying power of most writers; writing a gripping volume one is relatively easy, but keeping the quality up for two more outings? Not so easy. So here's the bad and the good of the trilogy business:

Paul Cornell has a CV thick with Doctor Who novelizations, comic books, and scripts for various Brit TV series. His Shadow Police series (London Falling, The Severed Streets, Who Killed Sherlock Holmes?) follows a group of London cops who police the supernatural underworld. So far, so high concept. The first novel, London Falling, was about a murderous witch and was solidly written and quite entertaining. The Severed Streets was dreadful. For one thing, having an actual writer, Neil Gaiman, appear as a secondary character in the novel must violate some kind of literary fourth wall protocol. It's also just silly. In addition to that faux pas, the novel had a murky, sluggish plot, and, worst of all, things got too serious. I can stomach an over-the-top fantasy/SF concept if the author gives me a wink every now and then to let me know he or she's aware of the silliness on offer, but a writer who can't crack a smile at their own bizarre creation? No thanks. Throughout volume two, all the main cop characters are living in various kinds of existential hell, and that made reading it a joyless slog. You must be wondering at this point why I bothered to read the next one. Foolishly, I was intrigued by the concept (someone kills the ghost of Sherlock Holmes) and hoped that an editor might have warned Cornell that his weapons-grade gravitas was misplaced. No such luck. The most recent novel is more of the same gloomy, turgid writing. It should also be pointed out that Cornell is poaching on a genre established by Ben Aaronovitch in his Rivers of London series which features--wait for it--a group of London coppers who police the supernatural. What are the odds? And why was Aaronovitch kind enough to put a blurb on Cornell's book? That's taking English politeness too far. So that's it, Cornell, you're now undead to me.

And then we have Robin Stevens. Her threesome of cozy murder mysteries for young readers are set in the 1930s and feature a pair of teenage sleuths, Mabel Wong and Daisy Wells, who go to a posh all-girls school in England. At first glance this sounds like something a committee made up of the BBC, the National Trust, and Country Life magazine might have cobbled together. Normally I'd run far, far away from something like this, but I'd come across a mention of the series in the Guardian that praised the quality of the writing. It also helped that I was working my way through Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels at the time and I needed some reading material to, as it were, detoxify with. Good choice on my part; although, oddly enough, like Ferrante's novels, Stevens' novels also feature a spiky female friendship. Her mysteries (Murder Most Unladylike, Arsenic for Tea, First Class Murder) distinguish themselves by being as well-written as anything in the cozy field, adult or otherwise. Stevens does not write down to her intended audience; in fact, it feels like she wants to challenge her readers. The characters and plots are far more complex than you'd expect to find in books aimed at early teen readers, there's a nice vein of humor running through all the books, and the mystery elements are really strong. The locked room mystery in First Class Murder is an excellent introduction to this sub-genre for young readers and compares well with adult examples. Stevens is writing more in this series, but I'd really like to see her take a crack at a full-on adult mystery.

I've started a great many trilogies but not finished most of them. The lesson here is that writers, even very good ones, have trouble spinning out a high-concept premise over more than one book. The fault lies with publishers, who are always trying to find ways to hook readers into committing to a series of books (and purchases). It's hard to blame them for trying to maximize profits, but it's counter-productive when you kill a reader's interest in an author by pushing him or her into producing crappy work.

Paul Cornell has a CV thick with Doctor Who novelizations, comic books, and scripts for various Brit TV series. His Shadow Police series (London Falling, The Severed Streets, Who Killed Sherlock Holmes?) follows a group of London cops who police the supernatural underworld. So far, so high concept. The first novel, London Falling, was about a murderous witch and was solidly written and quite entertaining. The Severed Streets was dreadful. For one thing, having an actual writer, Neil Gaiman, appear as a secondary character in the novel must violate some kind of literary fourth wall protocol. It's also just silly. In addition to that faux pas, the novel had a murky, sluggish plot, and, worst of all, things got too serious. I can stomach an over-the-top fantasy/SF concept if the author gives me a wink every now and then to let me know he or she's aware of the silliness on offer, but a writer who can't crack a smile at their own bizarre creation? No thanks. Throughout volume two, all the main cop characters are living in various kinds of existential hell, and that made reading it a joyless slog. You must be wondering at this point why I bothered to read the next one. Foolishly, I was intrigued by the concept (someone kills the ghost of Sherlock Holmes) and hoped that an editor might have warned Cornell that his weapons-grade gravitas was misplaced. No such luck. The most recent novel is more of the same gloomy, turgid writing. It should also be pointed out that Cornell is poaching on a genre established by Ben Aaronovitch in his Rivers of London series which features--wait for it--a group of London coppers who police the supernatural. What are the odds? And why was Aaronovitch kind enough to put a blurb on Cornell's book? That's taking English politeness too far. So that's it, Cornell, you're now undead to me.

And then we have Robin Stevens. Her threesome of cozy murder mysteries for young readers are set in the 1930s and feature a pair of teenage sleuths, Mabel Wong and Daisy Wells, who go to a posh all-girls school in England. At first glance this sounds like something a committee made up of the BBC, the National Trust, and Country Life magazine might have cobbled together. Normally I'd run far, far away from something like this, but I'd come across a mention of the series in the Guardian that praised the quality of the writing. It also helped that I was working my way through Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan novels at the time and I needed some reading material to, as it were, detoxify with. Good choice on my part; although, oddly enough, like Ferrante's novels, Stevens' novels also feature a spiky female friendship. Her mysteries (Murder Most Unladylike, Arsenic for Tea, First Class Murder) distinguish themselves by being as well-written as anything in the cozy field, adult or otherwise. Stevens does not write down to her intended audience; in fact, it feels like she wants to challenge her readers. The characters and plots are far more complex than you'd expect to find in books aimed at early teen readers, there's a nice vein of humor running through all the books, and the mystery elements are really strong. The locked room mystery in First Class Murder is an excellent introduction to this sub-genre for young readers and compares well with adult examples. Stevens is writing more in this series, but I'd really like to see her take a crack at a full-on adult mystery.

I've started a great many trilogies but not finished most of them. The lesson here is that writers, even very good ones, have trouble spinning out a high-concept premise over more than one book. The fault lies with publishers, who are always trying to find ways to hook readers into committing to a series of books (and purchases). It's hard to blame them for trying to maximize profits, but it's counter-productive when you kill a reader's interest in an author by pushing him or her into producing crappy work.

Monday, November 7, 2016

Film Review: Free State of Jones (2016)

The most interesting part of this film is its subject matter, not the filmmaking itself. Matthew McConaughey plays Newton Knight, a medical orderly in the Confederate Army who deserts after learning that a new law allows the sons of the richest slaveholders to be excused military service. Knight returns to his home in Jones County, Mississippi, where he's hunted by the local Confederate militia. After they burn down his home, Knight hides out in a swamp with some runaway slaves. This becomes the nucleus of a guerilla group that eventually numbers in the hundreds and battles the local Confederate forces. Knight and his men end up controlling a significant swath of Mississippi and declare the "free state of Jones", a land dedicated to the principle of egalitarianism for all men, no matter what their colour. The war ends and the Reconstruction period is followed by brutal suppression of black political activism by the KKK and plantation owners. Knight takes a black woman as his wife after the war, and a sub-plot set in the 1950s shows one of his male descendants, who is one-eighth black, fighting Jim Crow laws for the right to marry his white fiance.

The earnest, plodding, clunkiness of this biopic feels, at times, like a throwback to film styles and tropes from the '50s and '60s. 12 Years a Slave and Glory are set in the same era, but they told their stories with subtlety and cinematic flair without diminishing the messages they wanted to get across. Jones has no time for artistry. Dramatic and romantic elements are handled like assignments for a required university course, and the action sequences are staged like pageants. One battle set in a graveyard actually borders on the farcical.

By this point you might think I didn't like this film. Wrong. What sets it apart from a Glory or 12 Years a Slave is that it's eager and willing to tackle issues that don't normally get an airing in American films, specifically the subject of class warfare. At several points in the film it's explicitly stated that the Civil War was primarily about plantation owners, the plutocracy of the South, defending their capital interests with the lives of poor whites. Most films about this period in history might have ended with the conclusion of the war. Jones continues its study of class politics with the Reconstruction period, which, as far as I know, has never been dealt with in any film. The film makes it clear that the efforts of the KKK and their capitalist supporters were directed at denying blacks political power because that kind of power meant a tidal shift in the relationship between capital and labour. All those notions about white Southern notions of "honour" and ''tradition" and fear of black violence were just hogwash. Whites were only interested in instituting a system of legal peonage to replace slavery. In this way Jones emerges as a superior film to Glory and 12 Years a Slave because the latter two films are dealing in honorable platitudes: racism are slavery were bad. This film brings something new to the discussion by showing how racism is so often a screen behind which politicians and capitalists practice their black arts.

Free State of Jones is a flawed film from a purely cinematic point of view, but as an examination of an often poorly understood part of American history it really has no equal. And lest you think that this subject matter isn't worth re-examining in this day and age, check out the interview below with legendary film director William Friedkin. From the 6:23 mark onwards Friedkin defends the birth of the KKK. It's jaw-dropping stuff, and this from someone who's from the allegedly liberal bastion of Hollywood.

The earnest, plodding, clunkiness of this biopic feels, at times, like a throwback to film styles and tropes from the '50s and '60s. 12 Years a Slave and Glory are set in the same era, but they told their stories with subtlety and cinematic flair without diminishing the messages they wanted to get across. Jones has no time for artistry. Dramatic and romantic elements are handled like assignments for a required university course, and the action sequences are staged like pageants. One battle set in a graveyard actually borders on the farcical.

By this point you might think I didn't like this film. Wrong. What sets it apart from a Glory or 12 Years a Slave is that it's eager and willing to tackle issues that don't normally get an airing in American films, specifically the subject of class warfare. At several points in the film it's explicitly stated that the Civil War was primarily about plantation owners, the plutocracy of the South, defending their capital interests with the lives of poor whites. Most films about this period in history might have ended with the conclusion of the war. Jones continues its study of class politics with the Reconstruction period, which, as far as I know, has never been dealt with in any film. The film makes it clear that the efforts of the KKK and their capitalist supporters were directed at denying blacks political power because that kind of power meant a tidal shift in the relationship between capital and labour. All those notions about white Southern notions of "honour" and ''tradition" and fear of black violence were just hogwash. Whites were only interested in instituting a system of legal peonage to replace slavery. In this way Jones emerges as a superior film to Glory and 12 Years a Slave because the latter two films are dealing in honorable platitudes: racism are slavery were bad. This film brings something new to the discussion by showing how racism is so often a screen behind which politicians and capitalists practice their black arts.

Free State of Jones is a flawed film from a purely cinematic point of view, but as an examination of an often poorly understood part of American history it really has no equal. And lest you think that this subject matter isn't worth re-examining in this day and age, check out the interview below with legendary film director William Friedkin. From the 6:23 mark onwards Friedkin defends the birth of the KKK. It's jaw-dropping stuff, and this from someone who's from the allegedly liberal bastion of Hollywood.

Monday, October 31, 2016

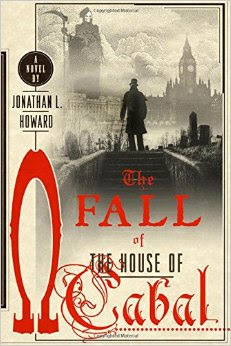

Book Review: The Fall of the House of Cabal (2016) by Jonathan L. Howard

Let's play sports analogies: In the field of fantasy/horror fiction, Jonathan L. Howard is a decathlete who regularly ends up on the podium. He's a 20-game winning pitcher who can paint the corners with the fastball, freeze batters with his curveball, and make them look foolish with the breaking ball. He's a centre in hockey who plays a 200-foot game and can be counted on for some Gordie Howe hat tricks every season. And now I've run out of sports I know anything about. My point, and I do have one, is that Howard is a writer who, within his particular field, is adept at any literary style you care to think of. Depending on what's called for, or as the mood takes him, he can do comedy (high and low), horror, big action set-pieces, mystery, wit, spookiness, and good old-fashioned ripping yarn adventure. His masterful skill as a literary shape-shifter is always most evident in his Cabal books, of which this is the fifth in the series.

This time out Johannes and his brother Horst are on the hunt for the Fountain of Youth. To get there they require the assistance of three women: a spider demon, a witch, and a detective. The Cabal novels take place in a steampunky Europe that looks and sounds roughly like the 1920s. Cabal & Co. journey to several supernatural realms, fight everything from ghouls to vampiric bankers to Satan himself, and it's all done with style and effervescent inventiveness. That description might make it sound like the author has overegged his pudding (a common fault in the steampunk genre), but Howard is disciplined enough to never introduce a new story element without giving it the proper level of development and creative attention.

What might be most striking about this latest entry in the Cabal franchise is that it still holds the reader's attention. The woods are full of fantasy writers who crank out trilogies, quartets, and quintets, but it's rare for any of these shelf-fillers to maintain a high standard beyond the first in the series. The Cabal books are consistently excellent. One reason for this is that Howard dabbles in a different type of story with each outing. The series has included a mystery story, a picaresque adventure set in a carnival, a Lovecraftian epic, and a war story of sorts. The other factor that accounts for the longevity of the series is that Howard brought in Horst to be a foil for Johannes. Horst is a vampire with a heart of gold, and his geniality, humour and humanity act to leaven the sardonic misanthropy of Johannes.

You don't have to be a fantasy/horror fan to enjoy this series. Howard's main aim is to amuse, and what stands out most strongly about the Cabal books is their wit. There are lots of things that go bump, slither, and bite in the night, but the overall tone is comic with a generous side order of rip-roaring adventure. The humour is often acidic, the writing sometimes donnish and orotund (I sense the ghost of mystery writer Michael Innes is present here), and there is absolutely never a dull moment. And here's hoping Horst Cabal gets a standalone novel in the Cabal universe.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)