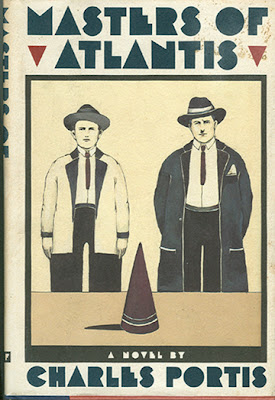

If Masters of Atlantis isn't the Great American Novel, it's surely the Great American Comic Novel. Say the words "great novel" and one instantly thinks of a work of fiction that tackles important moral questions, significant social issues, and moments of historic import; the sort of book one imagines was written by someone with a brow constantly furrowed in thought, living in a room with a single window facing a brick wall, and who only took brief breaks from the Underwood in order to light unfiltered Camels, all the better to furrow his or her brow even more. But does a nation's great novel have to adopt a stern and forbidding mien? By my own definition a great national novel should be one that you could hand to an extraterrestrial and say, "Here's the one book that tells you all about the essential character of the people whose nation you've just landed in/enslaved/vaporized." And by that criteria Masters of Atlantis by Charles Portis (author of True Grit) is, for me, the Great American Novel. And I like to imagine it was written in the summer on a porch shaded by wisteria vines, the author stopping occasionally for a snack of iced tea and red velvet cake.

From the outside looking in, America's personality dial is permanently set to 11 with citizens who are charming, maddening, innocent, foolish, xenophobic, gullible, optimistic, crafty, adventurous, bigoted, energetic, and ignorant, not forgetting all the go-getters, do-gooders and flim-flam men. This crazy quilt of emotions and characters is brilliantly portrayed in Masters, woven into a story that revolves around what might be the core of the American character: belief. More on this later.

The novel opens at the end of World War One with young Lamar Jimmerson, an American soldier, being sold the Codex Pappus, a bundle of papers that's supposed to represent the collected wisdom of the lost city of Atlantis. And from that beginning, Jimmerson, who has an unshakable belief in his Atlantean lore, more or less accidentally founds a cult called Gnomonism with himself at its head. His title is the "Master." The cult's popularity waxes and wanes, reaching its zenith in the 1930s, and ending in that most American of dwellings, a double-wide trailer home. The plot, like so many of the characters in the book, is almost rudderless, but this is far from being a fault, it's simply reflecting the rootless, peripatetic side of American life.

Along the way Jimmerson is aided and hindered by a cavalcade of American archetypes and eccentrics. The most notable of the bunch is Austin Popper and his sidekick Squanto, a talking blue jay. Popper is the distillate that would result from boiling down Elmer Gantry, Bob Hope and Foghorn Leghorn. Jimmerson is a kindly fool whose affability and credulity blinds him to the charlatans and nitwits who are pulled into Gnomonism's weak gravitational field. The female characters, it should be noted, are the only ones who seem to be possessed with an ounce of common sense.

Portis' comic style is best described as deadpan; he tells tall tales in the plainest possible way, and that matter-of-factness, his attention to the niggling details of eccentricity, produces some sublime humor. Portis' comedy is never shouty or jokey; it's like a low frequency vibration that turns solids into liquids, or in this case, turns some of the more self-important aspects of the American character into comic gold. And like the very best comic writers (P.G. Wodehouse springs to mind) you can flip to almost any page of the book and find something delightful:

"Through a friend at the big Chicago marketing firm of Targeted Sales, Inc., he got his hands on a mailing list titled Odd Birds of Illinois and Indiana, which, by no means exhaustive, contained the names of some seven hundred men who ordered strange merchandise through the mail, went to court often, wrote letters to the editor, wore unusual headgear, kept rooms that were filled with rocks or old newspapers. In short, independent thinkers who might be more receptive to the Atlantean lore than the general run of men."

And..

"You think you can treat me this way because I'm poor and have to go to night law school."

"All law schools should be conducted at night."

And...

"He boiled some eggs, a long business at this altitude, and made coffee with the same water. He ate two eggs and left two for Cezar. On one he idly scrawled, Help. Captive. Gypsy caravan."

If there's one grand, unifying theme to the novel it's Portis' identification of the fact that Americans are the most enthusiastic believers on the planet. Their nation was founded, in part, by people looking to follow religious beliefs that Europeans viewed as dangerous or eccentric, and ever since then the US has lead the world in the production of cults and crazes, everything from Mormonism to Scientology to birthers. It's a nation that sometimes seems to be filled with people who think that with just the right formula or mantra or revelation or algorithm, the final, absolute, one-size-fits-all Truth will be revealed to the chosen. And no other country could produce so many social clubs like the Shriners, Moose Lodge, Optimists, and Rotarians, just to name a few. It would seem that if you took three random Americans and locked them in a room, after an hour they would emerge with a new religion, conspiracy theory or service club. Possibly all three. But what Americans believe in most of all is America; it's a cult and a religion, and if you don't believe me just take note of how omnipresent the American flag is in the American landscape. The US is awash in representations of Old Glory, and in that regard it's unique among democracies. Flag worship is the litmus test for any totalitarian state, but in the US of A the common citizens have turned the Stars and Stripes into a red, white and blue Shroud of Turin.

I've read Masters several times, and what motivated me to do this review is The Master, Paul Thomas Anderson's latest film. It's a pretty poor effort (my review) about the leader of a Scientology-like cult. It's really the photographic negative, unfunny version of Masters of Atlantis, but it made me wish someone, preferably the Coen brothers, would take a crack at filming Portis' novel. But until that happens, and you want to experience a fictional look at America's obsession with cults, stick to Portis.

Showing posts with label Coen brothers. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Coen brothers. Show all posts

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Film Review: True Grit (2010) vs. True Grit (1969)

After recently seeing the Coen brothers True Grit for the second time (on DVD), and having seen the John Wayne-starring version on numerous occasions, I can definitely say that...I'm not sure which is better.

After recently seeing the Coen brothers True Grit for the second time (on DVD), and having seen the John Wayne-starring version on numerous occasions, I can definitely say that...I'm not sure which is better.Let's begin with the stars. Jeff Bridges is a masterful actor, better than John Wayne ever was, but in this role he gives a rather predictable performance. He talks in a gruff, growly monotone, and basically tries to let Charles Portis' brilliant dialogue do the work for him. Wayne, to be honest, hammed it up. He set the John Wayne dial at 11. Bridges creates a more believable character, but Wayne extracted more entertainment value out of the role.

Moving down the cast list, Matt Damon and Hailee Stanfield are a quantum improvement over Glen Campbell and Kim Darby. Campbell shouldn't have been allowed in home movies let alone feature films, and Darby I found irritating instead of determined. When it comes to the minor characters, however, the older version wins hands down, with A-list character actors such as Robert Duvall as Ned Pepper, Dennis Hopper as Moon, and Strother Martin as Stonehill, the horse trader unlucky enough to barter with Mattie Ross. For the sake of comparison, check out Martin's scene with Mattie and compare it with the Coen version using an actor named Dakin Matthews. The two sequences are virtually identical, but Martin turns the scene into a small comic gem. Matthews just reads the script.

The 1969 True Grit has a conventionally pretty look to it. The Coens make their True Grit look, well, gritty. And that's a plus. The Portis novel was a de-romanticized version of the Wild West, and the Coens remain true to that idea by showing us buildings and people that almost give off the smell of manure, sweat and tobacco. This tough look also makes Mattie's journey into the wilderness seem that much more daunting and dangerous. The 1969 version made the trip seem like a bit of a holiday.

The backbone of any western is the action sequences, and in this regard the Coens fall flat. Henry Hathaway, the 1969 director, had been directing westerns and action movies since the advent of sound, and it shows. His action sequences are fluid and energetic. The Coens, on the other hand, have a static, unimaginative approach to action. This may be where their committee approach to directing lets them down. The scene in the dugout cabin where Rooster Cogburn questions Moon and Quincy is a good comparison point. Hathaway builds tension in the scene by having Moon become increasngly agitated due to his leg wound. He also parallels this action by having Quincy become more violent as he cleans a turkey carcass (the Coens omit the turkey), while at the same time he's showing us Mattie becoming more distressed by the rising tension and anger. When violence suddenly erupts it's like a hissing boiler suddenly exploding. The Coen version has Moon talking in a flat montone up until he's mortally wounded by Quincy. The whole scene is shot with a minimum of fuss and a minimum of excitement.

The winner? Both. I just wish Glen Campbell hadn't been in the original and that the Coens could have had a coaching session from John Woo.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)