Is American Sniper as morally blind, jingoistic and lacking in political context as a host of commentators and critics have described it? Yes. Yes it is. Most of the critical flak has been aimed at director Clint Eastwood, but I'd say scriptwriter Jason Hall and producer/star Bradley Cooper deserve more of the blame.

Eastwood's direction here ranges from efficient to perfunctory to downright lazy, but I'm calling out Hall and Cooper for a jaw-droppingly bad script that feels as though it was crafted by a committee comprised of PR people for the NRA and the Tea Party. The script does such a thorough job of ducking the hard and nasty truths about Chris Kyle and the war in Iraq that it should qualify as a fantasy film. Kyle's ghostwritten autobiography and subsequent revelations about his post-war life made it clear that he was a racist, a sociopath, and a congenital liar who fantasized about killing civilians. These qualities probably helped make him grade A material for the Navy SEALS, but why would a scriptwriter and producer go so far out of their way to whitewash a character who was, to put it mildly, halfway to being a serial killer? The script also cuts and pastes the historical record in order to suggest that Iraq was behind the 9/11 attacks. I'd say this kind of revisionism, and the film's fawning celebration of good ole boy machismo, is a calculated and cynical strategy to appeal to a specific and considerable American demographic; namely the kind of people who flesh out the ranks of the Tea Party; holiday in Branson, MO; fill the stands at NASCAR races; attend gun shows on Saturdays and pack the pews of megachurches on Sundays. This is the audience this film is tailor-made for. American Sniper glorifies, even beatifies, the values and myths they hold dear and does it with a rigorous disregard for the thorny inconveniences of irony, historical accuracy, psychological insight, and the moral and political consequences of military actions.

American Sniper also continues a tradition of mainstream Hollywood films portraying wars purely in terms of their effect on American soldiers and civilians. Vietnam films, even politically liberal ones such as Coming Home, had nothing to say about the two million Vietnamese killed in the war. The Hurt Locker, another film about the Iraq war, is very similar in tone and subject matter to American Sniper and also shares its lack of interest in the war's impact on Iraqis. If your only knowledge of Iraq came from those two films you'd be left with the idea that Iraq was entirely filled with terrorists and their civilian supporters. The combination of two wars and brutal economic sanctions between those wars have led to the deaths, by some estimates, of a million Iraqis and the displacement of millions more. According to Hollywood's moral accounting, none of that counts for anything compared to the temporary psychological stresses suffered by one soldier, Chris Kyle, and his wife.

Looked at purely from a cinematic perspective, Eastwood's direction is robotic. The plentiful action sequences are visually dull and lack tension, the boot camp section is an afterthought, and the scenes that show Kyle suffering from PTSD make it look like it's a condition akin to having a few too many coffees. I think at some point in pre-production everyone decided this best way to approach this film was to be non-judgmental and let the facts (according to Chris Kyle) speak for themselves. That's translated into a dull, witless, nasty film that might have worked better if it had paraphrased the title of an earlier, better Eastwood film: how does White Sniper, Black Heart sound?

Showing posts with label Clint Eastwood. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Clint Eastwood. Show all posts

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Monday, May 28, 2012

Film Review: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

This isn't going to be a full-on review of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; let's just take it as a given that you've seen it, you love it, and you agree that it fits into any list of the top one hundred films of all time. An aspect of GBU that hasn't had much, or any, recognition is that the plot isn't just about three men hunting for hidden gold. That's just the top layer to the story. On a symbolic level GBU is about Christ and the Devil fighting for Tuco's soul. If you've finished snorting in derision, I'll continue.

Let's begin with the naming of the characters. Only Tuco, the Ugly, is given an actual name. The Bad is called Angel Eyes, and the Good is named Blondie. The last two have been given symbolic names. Angel Eyes is a reference to Satan as a fallen angel, and Blondie, well, who's always presented in religious paintings as being blonde? The good and bad references seem obvious, but why is Tuco identified as ugly? What does ugly mean in this context? Eli Wallach's certainly no oil painting, but what I'm guessing it refers to is that Tuco, like all mankind, is living in original sin; he's made in God's image, but is marred, made ugly, by orginal sin. Sergio Leone pretty much annouces what he's up to off the top with freeze frames on each character that are accompanied by a caption identifying them as good, bad or ugly. Once he's done this then you know this isn't going to be your average western.

Angel Eyes' satanic character is made explicit early in the film when, after killing two people who've each hired him to kill the other, he remarks to the last victim that when he's paid he always sees a job through to the end. According to folklore one must never do a deal with the Devil because he'll always find a way to turn the tables on you, and that's exactly what we see happen when we first meet Angel Eyes.

Blondie's credentials as Christ are even more apparent. In fact, at one point Angel Eyes refers to him as Tuco's guardian angel, and, just on cue, the sound of a heavenly choir rises in the background. When Tuco takes the injured Blondie to a monastery/hospital the room he's put in conveniently has a painting of the cruxifiction just outside it, which Tuco prays in front of for a brief moment. Blondie's holiness becomes more explicit once the action moves to the Civil War battle by the river. Blondie is appalled by the loss of men and tells the dying commanding officer (to whom he administers a kind of last rites by giving him a bottle of booze) to expect "good news" soon. He and Tuco blow up the bridge and thus end the battle. Blondie's Christ-like nature becomes explicit shortly after he and Tuco cross the river. Blondie goes into a ruined church and comforts a dying soldier by giving him a cigarillo and his coat. The way this scene is filmed suggests that this isn't just an act of random kindness, this is to be taken as an act of divine mercy.

Tuco, despite acting in a decidedly unholy way, is quick to use religious imagery. He crosses himself virtually every time he comes across a dead body, and he tells Blondie that when he, Tuco, is hanging at the end of a rope he can feel the Devil "biting his ass." In one of the film's key moments, Tuco is about to hang Blondie in revenge for having abandoned him in the desert. The sound of artillery is rumbling in the background and Tuco comments that there was also thunder heard when Judas hanged himself. Tuco's split nature is shown during a brilliant scene with his brother Pablo, a priest, at the monastery. Tuco greets his brother with warmth, but his brother gives him a very un-Christian cold shoulder. In the same scene Tuco lets his brother know that his choice of a life of crime was not his first choice, and that Pablo's decision to become a priest was a form of cowardice. The scene leaves us knowing that Tuco is, to a degree, morally conflicted.

The fight for Tuco's soul first becomes obvious in the scam Blondie and he run. Blondie turns Tuco in for the reward money and then shoots away the rope when Tuco's about to be hung. Each time Tuco is about to face death a list of his crimes is read out by the local sherriff. It's as though he's facing a roll call of his sins, or, because he's allowed himself to be put in this position, he's confessing his sins. And after each confession he's granted forgiveness by Blondie/Christ who shoots the rope. Blondie ends the relationship, and on a symbolic level it's because he thinks Tuco has received a moral lesson about his life of crime.

The final shootout in the cemetery brings all the religious themes to a head. To begin with we have the gold buried in a grave, a clear warning that worldly wealth equals death. Angel Eyes is killed by Blondie and slides into an open grave. Not content with having killed Angel Eyes, Blondie then shoots his fallen hat and gun into the grave. It looks very much as though Angel Eyes is being cast back down to Hell. Blondie then makes Tuco put a rope around his own neck and stand on a cross marking a grave. Blondie then rides off. Tuco is left perched precariously on a cross, staring down at bags of gold lying on the ground. The message seems obvious: as long as Tuco stays on the Holy Cross he stays alive; if he leaves the cross for the gold, for worldliness, he dies, and not just in this world. The juxtaposition of shots showing Tuco's desperation to stay on the cross and his view of the gold bags couldn't make this any clearer. After Blondie's judged that Tuco has absorbed yet another lesson on the error of his ways, he emerges from hiding and shoots away the rope. Tuco lands directly on the gold and then we get a freeze frame in which each of the three characters is once again identified as good, bad and ugly. Leone certainly knew how to drive a point home.

It's not as though Leone didn't mix symbolism into his other spaghetti westerns. In A Fistful of Dollars the family that's been split apart by Ramon is clearly meant to be the Holy Family. Leone also throws in some mythological elements when he has Joe, Clint Eastwood's character, hidden in a coffin and carried in a wagon driven by a Charon-like figure (a coffin maker) to the Underworld (an abandoned mine shaft). There he finds safety and forges a magical shield (an iron breastplate), which he wears when he returns to the land of the living. Like any god his arrival on Earth is announced with thunder and lightning (several sticks of dynamite), and Ramon is defeated because his hero-like ability to hit a man's heart with every rifle shot can't beat Joe's magical shield.

I don't think Leone meant for any of the religious or mythological references in his westerns to be taken too seriously. He used these themes and symbols to give his stories a subliminal resonance and weight. Without these elements his films would be more stylish versions of standard American westerns. One proof of this is Once Upon a Time in the West, which feels less substantial than Leone's other westerns because it omits religious and mythological motifs. Instead we get a rather muddy plot that contains some anti-capitalist rhetoric and not much else. The anti-capitalist theme was a common element in a lot of Italian films at the time, and I'd guess that Bernardo Bertolucci's involvement in the script probably had a lot to do with that.

I may be deluded or off-base with some of my arguments about the religious content of GBU, but give it another watch and see if my thesis doesn't hold up. The two clips below make up the final shootout from the film and I think it proves my point(s). The second clip has bonus Hebrew sub-titles! Here endeth the lesson.

Related posts:

Film Review: Duck You Sucker

Let's begin with the naming of the characters. Only Tuco, the Ugly, is given an actual name. The Bad is called Angel Eyes, and the Good is named Blondie. The last two have been given symbolic names. Angel Eyes is a reference to Satan as a fallen angel, and Blondie, well, who's always presented in religious paintings as being blonde? The good and bad references seem obvious, but why is Tuco identified as ugly? What does ugly mean in this context? Eli Wallach's certainly no oil painting, but what I'm guessing it refers to is that Tuco, like all mankind, is living in original sin; he's made in God's image, but is marred, made ugly, by orginal sin. Sergio Leone pretty much annouces what he's up to off the top with freeze frames on each character that are accompanied by a caption identifying them as good, bad or ugly. Once he's done this then you know this isn't going to be your average western.

Angel Eyes' satanic character is made explicit early in the film when, after killing two people who've each hired him to kill the other, he remarks to the last victim that when he's paid he always sees a job through to the end. According to folklore one must never do a deal with the Devil because he'll always find a way to turn the tables on you, and that's exactly what we see happen when we first meet Angel Eyes.

Blondie's credentials as Christ are even more apparent. In fact, at one point Angel Eyes refers to him as Tuco's guardian angel, and, just on cue, the sound of a heavenly choir rises in the background. When Tuco takes the injured Blondie to a monastery/hospital the room he's put in conveniently has a painting of the cruxifiction just outside it, which Tuco prays in front of for a brief moment. Blondie's holiness becomes more explicit once the action moves to the Civil War battle by the river. Blondie is appalled by the loss of men and tells the dying commanding officer (to whom he administers a kind of last rites by giving him a bottle of booze) to expect "good news" soon. He and Tuco blow up the bridge and thus end the battle. Blondie's Christ-like nature becomes explicit shortly after he and Tuco cross the river. Blondie goes into a ruined church and comforts a dying soldier by giving him a cigarillo and his coat. The way this scene is filmed suggests that this isn't just an act of random kindness, this is to be taken as an act of divine mercy.

Tuco, despite acting in a decidedly unholy way, is quick to use religious imagery. He crosses himself virtually every time he comes across a dead body, and he tells Blondie that when he, Tuco, is hanging at the end of a rope he can feel the Devil "biting his ass." In one of the film's key moments, Tuco is about to hang Blondie in revenge for having abandoned him in the desert. The sound of artillery is rumbling in the background and Tuco comments that there was also thunder heard when Judas hanged himself. Tuco's split nature is shown during a brilliant scene with his brother Pablo, a priest, at the monastery. Tuco greets his brother with warmth, but his brother gives him a very un-Christian cold shoulder. In the same scene Tuco lets his brother know that his choice of a life of crime was not his first choice, and that Pablo's decision to become a priest was a form of cowardice. The scene leaves us knowing that Tuco is, to a degree, morally conflicted.

The fight for Tuco's soul first becomes obvious in the scam Blondie and he run. Blondie turns Tuco in for the reward money and then shoots away the rope when Tuco's about to be hung. Each time Tuco is about to face death a list of his crimes is read out by the local sherriff. It's as though he's facing a roll call of his sins, or, because he's allowed himself to be put in this position, he's confessing his sins. And after each confession he's granted forgiveness by Blondie/Christ who shoots the rope. Blondie ends the relationship, and on a symbolic level it's because he thinks Tuco has received a moral lesson about his life of crime.

The final shootout in the cemetery brings all the religious themes to a head. To begin with we have the gold buried in a grave, a clear warning that worldly wealth equals death. Angel Eyes is killed by Blondie and slides into an open grave. Not content with having killed Angel Eyes, Blondie then shoots his fallen hat and gun into the grave. It looks very much as though Angel Eyes is being cast back down to Hell. Blondie then makes Tuco put a rope around his own neck and stand on a cross marking a grave. Blondie then rides off. Tuco is left perched precariously on a cross, staring down at bags of gold lying on the ground. The message seems obvious: as long as Tuco stays on the Holy Cross he stays alive; if he leaves the cross for the gold, for worldliness, he dies, and not just in this world. The juxtaposition of shots showing Tuco's desperation to stay on the cross and his view of the gold bags couldn't make this any clearer. After Blondie's judged that Tuco has absorbed yet another lesson on the error of his ways, he emerges from hiding and shoots away the rope. Tuco lands directly on the gold and then we get a freeze frame in which each of the three characters is once again identified as good, bad and ugly. Leone certainly knew how to drive a point home.

It's not as though Leone didn't mix symbolism into his other spaghetti westerns. In A Fistful of Dollars the family that's been split apart by Ramon is clearly meant to be the Holy Family. Leone also throws in some mythological elements when he has Joe, Clint Eastwood's character, hidden in a coffin and carried in a wagon driven by a Charon-like figure (a coffin maker) to the Underworld (an abandoned mine shaft). There he finds safety and forges a magical shield (an iron breastplate), which he wears when he returns to the land of the living. Like any god his arrival on Earth is announced with thunder and lightning (several sticks of dynamite), and Ramon is defeated because his hero-like ability to hit a man's heart with every rifle shot can't beat Joe's magical shield.

I don't think Leone meant for any of the religious or mythological references in his westerns to be taken too seriously. He used these themes and symbols to give his stories a subliminal resonance and weight. Without these elements his films would be more stylish versions of standard American westerns. One proof of this is Once Upon a Time in the West, which feels less substantial than Leone's other westerns because it omits religious and mythological motifs. Instead we get a rather muddy plot that contains some anti-capitalist rhetoric and not much else. The anti-capitalist theme was a common element in a lot of Italian films at the time, and I'd guess that Bernardo Bertolucci's involvement in the script probably had a lot to do with that.

I may be deluded or off-base with some of my arguments about the religious content of GBU, but give it another watch and see if my thesis doesn't hold up. The two clips below make up the final shootout from the film and I think it proves my point(s). The second clip has bonus Hebrew sub-titles! Here endeth the lesson.

Related posts:

Film Review: Duck You Sucker

Wednesday, February 22, 2012

Film Review: Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)

In 1974 I was 17 and only one year away from being legally eligible to see the R-rated Thunderbolt and Lightfoot in the theatre. It was a film I wanted to see very badly because it offered the combination of Clint Eastwood, violence and female nudity. My peers and I all tried to get in to see it, and we all failed. Theatres in Winnipeg took R-ratings very seriously. I finally saw it maybe 5 or 6 years later and thought it was pretty damn cool, just what I was hoping for.

I saw it again this past week and have to revise my opinion somewhat. While in most respects it remains a typical example of 1970s action movies, there are some odd angles to it that are worth a second look. The first is the bromance between Clint Eastwood (Thunderbolt) and the much younger Jeff Bridges (Lightfoot). In 1974 bromance was a term that was twenty years away from being invented, but the relationship between the two leads in this film has to be the template for all the movie bromances that followed. The duo meet cute (in action movie terms), do some bonding over beers and bimbos, and then consummate their relationship with a bank robbery in Montana. What's a bit different about this bromance is that Thunderbolt and Lightfoot are so visibly taken with each other. They do everything but exchange friendship rings. There isn't quite a homoerotic vibe to their relationship, but their enthusiasm for each other is a bit odd for the standards of the '70s. Of course, this bromance shouldn't really be a surprise given that the film was written and directed by Michael Cimino. Cimino later did The Deer Hunter, the grand opera of bromances.

Thunderbolt meets the '70s quota for gratuituous female nudity, but it does so with a leering, hairy-palmed awkwardness that makes it feel like Cimino might have penned the script when he was sixteen. What's odder is that sometimes the standard male heterosexual lustfulness spills over into something gayer. In once scene a brutish character played by George Kennedy insists that Lightfoot describe a naked woman he saw that day. Lightfoot teases him with the description and then gives him a mock kiss a la something Bugs Bunny would do to Elmer Fudd. Also, as part of the heist Lightfoot has to dress in drag and attract the sexual attention of a clerk. Another scene has a minor character telling Thunderbolt about a prank he pulled involving sticking his dick in another man's hand. Sometimes you have to wonder what audience Cimino thought he was writing for. And I won't even mention the plentiful use of phallic symbols.

The last major oddity is the ending, which turns what has been a nasty, rude, tough, fun heist film into something sadder and more serious. The heist, as is often the case in films like this, goes badly awry. George Kennedy double-crosses Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, knocking them both out in the process, and putting Lightfoot down with a particularly vicious kick to the head. Kennedy meets a grisly end shortly thereafter and T & L escape. The next day our two penniless heroes are thumbing a ride and come upon $500,000 stashed from a previous robbery of the same bank (it all makes sense in the context of the story) inside a one-room schoolhouse now being used as museum. This looks like a happy ending, but the kick Lightfoot took has caused serious brain damage, and in the last 6 or 7 minutes of the film we see him go from dazed to dopey to partially paralyzed to dead. It's a shocking and bleak twist to the end and it seems to be an oblique commentary on Vietnam. The Thunderbolt character is described at several points as a Korean War hero, and one of the last things Lightfoot says before he dies is that he now feels like a hero because he's finally accomplished something: he pulled off his role in the robbery. Like the Vietnam War, Thunderbolt ends with nothing really accomplished and a dead young man.

Thunderbolt is mostly well-made, with some nice cinematography, brisk action sequences and a scene-stealing performance from Jeff Bridges in one of his earliest roles.The plot has one or two holes, but otherwise Thunderbolt is an entertaining crime flick, albeit one that's a bit odd and pervy, but that only makes it more interesting.

I saw it again this past week and have to revise my opinion somewhat. While in most respects it remains a typical example of 1970s action movies, there are some odd angles to it that are worth a second look. The first is the bromance between Clint Eastwood (Thunderbolt) and the much younger Jeff Bridges (Lightfoot). In 1974 bromance was a term that was twenty years away from being invented, but the relationship between the two leads in this film has to be the template for all the movie bromances that followed. The duo meet cute (in action movie terms), do some bonding over beers and bimbos, and then consummate their relationship with a bank robbery in Montana. What's a bit different about this bromance is that Thunderbolt and Lightfoot are so visibly taken with each other. They do everything but exchange friendship rings. There isn't quite a homoerotic vibe to their relationship, but their enthusiasm for each other is a bit odd for the standards of the '70s. Of course, this bromance shouldn't really be a surprise given that the film was written and directed by Michael Cimino. Cimino later did The Deer Hunter, the grand opera of bromances.

Thunderbolt meets the '70s quota for gratuituous female nudity, but it does so with a leering, hairy-palmed awkwardness that makes it feel like Cimino might have penned the script when he was sixteen. What's odder is that sometimes the standard male heterosexual lustfulness spills over into something gayer. In once scene a brutish character played by George Kennedy insists that Lightfoot describe a naked woman he saw that day. Lightfoot teases him with the description and then gives him a mock kiss a la something Bugs Bunny would do to Elmer Fudd. Also, as part of the heist Lightfoot has to dress in drag and attract the sexual attention of a clerk. Another scene has a minor character telling Thunderbolt about a prank he pulled involving sticking his dick in another man's hand. Sometimes you have to wonder what audience Cimino thought he was writing for. And I won't even mention the plentiful use of phallic symbols.

The last major oddity is the ending, which turns what has been a nasty, rude, tough, fun heist film into something sadder and more serious. The heist, as is often the case in films like this, goes badly awry. George Kennedy double-crosses Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, knocking them both out in the process, and putting Lightfoot down with a particularly vicious kick to the head. Kennedy meets a grisly end shortly thereafter and T & L escape. The next day our two penniless heroes are thumbing a ride and come upon $500,000 stashed from a previous robbery of the same bank (it all makes sense in the context of the story) inside a one-room schoolhouse now being used as museum. This looks like a happy ending, but the kick Lightfoot took has caused serious brain damage, and in the last 6 or 7 minutes of the film we see him go from dazed to dopey to partially paralyzed to dead. It's a shocking and bleak twist to the end and it seems to be an oblique commentary on Vietnam. The Thunderbolt character is described at several points as a Korean War hero, and one of the last things Lightfoot says before he dies is that he now feels like a hero because he's finally accomplished something: he pulled off his role in the robbery. Like the Vietnam War, Thunderbolt ends with nothing really accomplished and a dead young man.

Thunderbolt is mostly well-made, with some nice cinematography, brisk action sequences and a scene-stealing performance from Jeff Bridges in one of his earliest roles.The plot has one or two holes, but otherwise Thunderbolt is an entertaining crime flick, albeit one that's a bit odd and pervy, but that only makes it more interesting.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

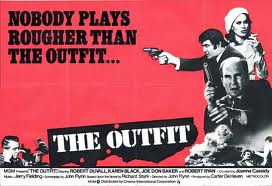

Film Review: The Outfit (1973)

I've written previously about the Parker novels by Richard Stark on this blog (you can read the post here), and this early 1970s adaptation of the novel by the same name comes closest to capturing the flavour of Stark's writing. Point Blank is the best film made from a Parker novel, but it's not really true to the spirit of the books. And although The Outfit feels more like its source material, it still manages to miss the boat. It's entertaining, but there's some wonkiness that's hard to overlook.

The first oddity is that short, balding Robert Duvall is cast in the Parker role. Now Duvall can play tough, but he just doesn't appear tough (why does he hold his gun in that odd way?), and Parker is certainly described as looking rangy and menacing. The second oddity is that his character is called Earl Macklin instead of Parker. I can't even guess why that change was made. Joe Don Baker plays Macklin's sidekick and he would have been a much better choice for the Parker character.

The story is one that Stark would recycle in Butcher's Moon: the Outfit has killed Macklin's brother in retaliation for he and Earl having robbed a bank a few years previously that was controlled by the Outfit. Macklin goes to the Outfit's boss and demands a payment of 250k as a penalty for killing his brother (such brotherly love). The Outfit refuses, and Macklin and his sidekick begin knocking over Outfit properties until they agree to pay the "fine." They try to double-cross Macklin and that turns out to be a bad idea.

And now a word about the Outfit. The Outfit is a feature of the old Parker novels, and it's one that now feels somewhat dated. To a certain degree it plays the role that SPECTRE did in the James Bond novels. Both are highly organized criminal enterprises with interests in all kinds of criminal activity. The Outfit is essentially the Mafia, only it seems to be run entirely run by WASPy types. In Parker's world, every city has a parallel criminal economy, and it's all run by the Outfit.

The scenes of Macklin knocking over Outfit properties are done very well, and a lot of Stark's terse, muscular dialogue makes it to the screen to great effect. The acting is equally fine, which isn't surprising given that cast is stuffed with veteran character actors, everyone from Elisha Cook to Robert Ryan. Some parts are more uneven. Bruce Surtees is the cinematographer (he shot a lot Clint Eastwood's films) and he gives some scenes a nicely gritty look, but a lot of other scenes just look like a made-for-TV movie. Macklin's relationship with his girlfriend, played by Karen Black, is pointless and has an unpleasantly abusive aspect. The ending is the biggest disappointment. It feels hastily assembled and finishes on a jokey note that is very un-Parker.

The Outfit is worth watching, but I wouldn't go out of my way to track it down.

The first oddity is that short, balding Robert Duvall is cast in the Parker role. Now Duvall can play tough, but he just doesn't appear tough (why does he hold his gun in that odd way?), and Parker is certainly described as looking rangy and menacing. The second oddity is that his character is called Earl Macklin instead of Parker. I can't even guess why that change was made. Joe Don Baker plays Macklin's sidekick and he would have been a much better choice for the Parker character.

The story is one that Stark would recycle in Butcher's Moon: the Outfit has killed Macklin's brother in retaliation for he and Earl having robbed a bank a few years previously that was controlled by the Outfit. Macklin goes to the Outfit's boss and demands a payment of 250k as a penalty for killing his brother (such brotherly love). The Outfit refuses, and Macklin and his sidekick begin knocking over Outfit properties until they agree to pay the "fine." They try to double-cross Macklin and that turns out to be a bad idea.

And now a word about the Outfit. The Outfit is a feature of the old Parker novels, and it's one that now feels somewhat dated. To a certain degree it plays the role that SPECTRE did in the James Bond novels. Both are highly organized criminal enterprises with interests in all kinds of criminal activity. The Outfit is essentially the Mafia, only it seems to be run entirely run by WASPy types. In Parker's world, every city has a parallel criminal economy, and it's all run by the Outfit.

The scenes of Macklin knocking over Outfit properties are done very well, and a lot of Stark's terse, muscular dialogue makes it to the screen to great effect. The acting is equally fine, which isn't surprising given that cast is stuffed with veteran character actors, everyone from Elisha Cook to Robert Ryan. Some parts are more uneven. Bruce Surtees is the cinematographer (he shot a lot Clint Eastwood's films) and he gives some scenes a nicely gritty look, but a lot of other scenes just look like a made-for-TV movie. Macklin's relationship with his girlfriend, played by Karen Black, is pointless and has an unpleasantly abusive aspect. The ending is the biggest disappointment. It feels hastily assembled and finishes on a jokey note that is very un-Parker.

The Outfit is worth watching, but I wouldn't go out of my way to track it down.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)