If you've ever read any of the Parker crime novels by Richard Stark (I've a got piece on him here), then there won't be many surprises waiting for you in the Wyatt novels by Garry Disher. The setting is Australia instead of the US, but in every other regard Wyatt is simply Parker's Down Under cousin. Not that there's anything wrong with that. Most genre writers ride on the coattails of the historical greats in their field, and in the case of crime/mystery fiction there are very few contemporary fictional sleuths/heroes who don't carry some of the DNA of Phillip Marlowe, Sherlock Holmes, Miss Marple, and, yes, Parker.

In Port Vila Blues Wyatt, a career thief every bit as ruthless and efficient as Parker, faces off against a bunch of corrupt cops after his latest burglary unearths a Tiffany brooch that leads to a crooked judge who's masterminding his own team of burglars. There's double-crosses, random acts of violence, and Wyatt has to get himself out of some very tight situations. The writing is good, but if you've read anything by Stark you're left wishing that he had not taken a twenty-five-year hiatus in writing Parker novels.

What's interesting about Parker, Wyatt and Lee Child's Jack Reacher (yet another of Parker's literary cousins) is the appeal these sociopaths have for readers. Yes, they are sociopaths. What distinguishes the firm of Parker, Wyatt & Reacher from other crime fiction heroes and anti-heroes is their utter cold-bloodedness, their disconnect from normal life and emotions, and their casual use of lethal and non-lethal violence. In the real world, people like this are behind bars for lengthy stretches or on death row, and society is happy that that's where they are. In fiction, however, a significant number of readers take a vicarious thrill in the remorseless actions of PW & R. It's rather disturbing and revealing that a great many people have a secret fantasy that involves either being a stone cold killer, or wishing that there was flinty-eyed avenging angel out there (take a bow, Jack Reacher) willing and eager to kill without mercy or hesitation in order to return the social order to its rightful balance. What separates PW & R from more traditional heroes is their thorough disconnect with normal human relationships and behavior. PW & R don't have hobbies, they have no permanent relationships, no living relatives, they have alliances rather than friendships, most quotidian human pleasures are a mystery to them, and the opposite sex only exists for casual sex. James Bond may have been the first hero of this type (here's my piece on Bond), but at least his sociopathy was moderated by rampant sensualism; PW & R are positively monk-like in their tastes--Reacher, for example, makes a fetish of only drinking black coffee.

I'll admit I'm a fan of PW & R, but it's something of a guilty pleasure. Like a lot of other readers, I guess I have a secret, perverse desire for an agent of chaos and violence to be at large in the world to disrupt my safe, predictable middle-class existence. I know that it would be best and safest to live in a Miss Marple world, but every once in a while I'd like to see PW & R blow through town and knock over a bank, gun down a crime lord, and break the arms of some thugs. But please, no casual sex with Miss Marple. Some worlds should never collide.

Showing posts with label Richard Stark. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Richard Stark. Show all posts

Monday, February 3, 2014

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

Book Review: The Prone Gunman (1981) by Jean-Patrick Manchette

The most pleasing thing about The Prone Gunman is how thoroughly Manchette deconstructs and warps the traditional crime thriller. One way he does this is to strip his novel right down to the studs. Characters are described in a sentence or two, the plot rushes forward constantly, there's a minimum of extraneous commentary or description, and the action is brutal, frequent and described in the bluntest terms. This is a thriller with all the window dressing stripped away, and once that's done the absurdities and cliches of the genre become very apparent. A lot of pulp crime novels from the 1950s and '60s were lean and tough (Richard Stark in his Parker novels took this style to a brilliant level), but Manchette adds a dash of existential despair to the mix that makes his novels something special. The previous Manchette novel I read was Fatale (review here), and in that one the deadly heroine eventually seems to crack up under the strain of being exposed to the scheming of the bourgeoisie. In The Prone Gunman the protagonist, Martin Terrier, has a more peculiar breakdown.

The plot is a carefully thought out collection of cliches. Terrier is a professional assassin working for a shadowy company or organization that may or may not be part of the French government. Terrier decides he wants to retire from the business and goes back to his hometown in the south of France where he hopes to reconnect with his teenage sweetheart. Not surprisingly, the company Terrier works for decides it doesn't want him to retire, it wants him dead. Terrier and his girlfriend, Anne, go on the run and the bodies start to pile up along with plot twists by the score. There's really nothing original in the story, except for Terrier's reaction once the twists and betrayals reach epidemic proportions. He becomes a mute. It isn't a ruse, he actually loses the will to speak after one rather painful betrayal. It's a bizarre development, but in a loopy way it makes sense. Heroes in this genre traditionally take a tremendous amount of mental and physical abuse; they're shot at and chased; live in fear of betrayal or discovery; suffer torture; live double lives; and are always looking over their shoulder. Somehow none of this seems to have any lasting effects on the hero. At the end of the novel they pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and walk into the sunset, all ready for their next adventure. Terrier has a nervous breakdown. Who wouldn't? Terrier has been exposed to all kinds of horrors, shocks and violence, and his reaction amounts to a declaration of existential fright at what's been happening to and around him. It's a startling plot twist, but it points out the absurdity of the mentally invulnerable action hero whose psyche can bear up under any amount of pressure.

Another cliche of the crime/spy thriller genre is that the hero must have a romantic or sexual partner. If it's a wife or girlfriend she usually exists in the story to be captured or threatened and thus complicate the hero's mission. Sometimes the female characters are just around for the sex, which gives the story some sexytime fun and confirms the hero's hetero status. But the one thing that's certain is that the hero will always be paired off with an attractive, even gorgeous, woman who will think he's just great in and out of bed. It's almost an ironclad rule for the genre; no chunky or spotty girls need apply. Manchette completely destroys this cliche. Terrier eventually loses his girlfriend because, well, he's a complete dud in the sack. It's a witty riff on one of the most tired conventions of the genre.

Manchette also has time to rubbish one of the sillier aspects of crime novels: the pointless obsession with technical details; in particular, the fascination with name-branding weaponry. Any crime or thriller writer worth his salt likes (insists) on giving his readers the names and specs for every gun that appears in the story. So when a hero or villain produces a weapon we're immediately told it's, say, a Heckler & Koch MP5 with flash suppressor using a 7.62mm round. Who cares? The important thing is that some guy is armed and dangerous. For all I know Heckler & Koch could be an Austrian ventriloquism act. Manchette itemizes every bit of weaponry and extends the cliche to name-branding weapon accessories. Weapon name-branding exists in thrillers to add some verisimilitude, but it seems ludicrous to add a dollop of reality to stories that are, by and large, as far-fetched as any fantasy novel. One example: the uber-successful Jack Reader thrillers (my review of Worth Dying For here) by Lee Child are a feast of tech specs, but the plots are relentlessly improbable.

The subversion of thriller cliches goes on right to the end of The Prone Gunman. Unlike the vast majority of thriller heroes, Terrier isn't allowed to walk off into the sunset or enjoy a warrior's noble death. He ends up brain-damaged, living in his hometown, a figure of fun for the patrons of the bar where he works as a waiter. It's the most inglorious possible finish for the hero of a thriller. At the very end we see that Terrier was nothing more than a tool, like a Heckler & Koch, used by his masters until he was broken, and then tossed away. If you have a deep love for the conventions of modern thrillers you might find this book a mite upsetting, but if you like to see literary tropes given a good kicking...enjoy.

The plot is a carefully thought out collection of cliches. Terrier is a professional assassin working for a shadowy company or organization that may or may not be part of the French government. Terrier decides he wants to retire from the business and goes back to his hometown in the south of France where he hopes to reconnect with his teenage sweetheart. Not surprisingly, the company Terrier works for decides it doesn't want him to retire, it wants him dead. Terrier and his girlfriend, Anne, go on the run and the bodies start to pile up along with plot twists by the score. There's really nothing original in the story, except for Terrier's reaction once the twists and betrayals reach epidemic proportions. He becomes a mute. It isn't a ruse, he actually loses the will to speak after one rather painful betrayal. It's a bizarre development, but in a loopy way it makes sense. Heroes in this genre traditionally take a tremendous amount of mental and physical abuse; they're shot at and chased; live in fear of betrayal or discovery; suffer torture; live double lives; and are always looking over their shoulder. Somehow none of this seems to have any lasting effects on the hero. At the end of the novel they pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and walk into the sunset, all ready for their next adventure. Terrier has a nervous breakdown. Who wouldn't? Terrier has been exposed to all kinds of horrors, shocks and violence, and his reaction amounts to a declaration of existential fright at what's been happening to and around him. It's a startling plot twist, but it points out the absurdity of the mentally invulnerable action hero whose psyche can bear up under any amount of pressure.

Another cliche of the crime/spy thriller genre is that the hero must have a romantic or sexual partner. If it's a wife or girlfriend she usually exists in the story to be captured or threatened and thus complicate the hero's mission. Sometimes the female characters are just around for the sex, which gives the story some sexytime fun and confirms the hero's hetero status. But the one thing that's certain is that the hero will always be paired off with an attractive, even gorgeous, woman who will think he's just great in and out of bed. It's almost an ironclad rule for the genre; no chunky or spotty girls need apply. Manchette completely destroys this cliche. Terrier eventually loses his girlfriend because, well, he's a complete dud in the sack. It's a witty riff on one of the most tired conventions of the genre.

Manchette also has time to rubbish one of the sillier aspects of crime novels: the pointless obsession with technical details; in particular, the fascination with name-branding weaponry. Any crime or thriller writer worth his salt likes (insists) on giving his readers the names and specs for every gun that appears in the story. So when a hero or villain produces a weapon we're immediately told it's, say, a Heckler & Koch MP5 with flash suppressor using a 7.62mm round. Who cares? The important thing is that some guy is armed and dangerous. For all I know Heckler & Koch could be an Austrian ventriloquism act. Manchette itemizes every bit of weaponry and extends the cliche to name-branding weapon accessories. Weapon name-branding exists in thrillers to add some verisimilitude, but it seems ludicrous to add a dollop of reality to stories that are, by and large, as far-fetched as any fantasy novel. One example: the uber-successful Jack Reader thrillers (my review of Worth Dying For here) by Lee Child are a feast of tech specs, but the plots are relentlessly improbable.

The subversion of thriller cliches goes on right to the end of The Prone Gunman. Unlike the vast majority of thriller heroes, Terrier isn't allowed to walk off into the sunset or enjoy a warrior's noble death. He ends up brain-damaged, living in his hometown, a figure of fun for the patrons of the bar where he works as a waiter. It's the most inglorious possible finish for the hero of a thriller. At the very end we see that Terrier was nothing more than a tool, like a Heckler & Koch, used by his masters until he was broken, and then tossed away. If you have a deep love for the conventions of modern thrillers you might find this book a mite upsetting, but if you like to see literary tropes given a good kicking...enjoy.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

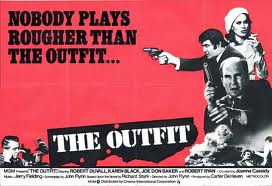

Film Review: The Outfit (1973)

I've written previously about the Parker novels by Richard Stark on this blog (you can read the post here), and this early 1970s adaptation of the novel by the same name comes closest to capturing the flavour of Stark's writing. Point Blank is the best film made from a Parker novel, but it's not really true to the spirit of the books. And although The Outfit feels more like its source material, it still manages to miss the boat. It's entertaining, but there's some wonkiness that's hard to overlook.

The first oddity is that short, balding Robert Duvall is cast in the Parker role. Now Duvall can play tough, but he just doesn't appear tough (why does he hold his gun in that odd way?), and Parker is certainly described as looking rangy and menacing. The second oddity is that his character is called Earl Macklin instead of Parker. I can't even guess why that change was made. Joe Don Baker plays Macklin's sidekick and he would have been a much better choice for the Parker character.

The story is one that Stark would recycle in Butcher's Moon: the Outfit has killed Macklin's brother in retaliation for he and Earl having robbed a bank a few years previously that was controlled by the Outfit. Macklin goes to the Outfit's boss and demands a payment of 250k as a penalty for killing his brother (such brotherly love). The Outfit refuses, and Macklin and his sidekick begin knocking over Outfit properties until they agree to pay the "fine." They try to double-cross Macklin and that turns out to be a bad idea.

And now a word about the Outfit. The Outfit is a feature of the old Parker novels, and it's one that now feels somewhat dated. To a certain degree it plays the role that SPECTRE did in the James Bond novels. Both are highly organized criminal enterprises with interests in all kinds of criminal activity. The Outfit is essentially the Mafia, only it seems to be run entirely run by WASPy types. In Parker's world, every city has a parallel criminal economy, and it's all run by the Outfit.

The scenes of Macklin knocking over Outfit properties are done very well, and a lot of Stark's terse, muscular dialogue makes it to the screen to great effect. The acting is equally fine, which isn't surprising given that cast is stuffed with veteran character actors, everyone from Elisha Cook to Robert Ryan. Some parts are more uneven. Bruce Surtees is the cinematographer (he shot a lot Clint Eastwood's films) and he gives some scenes a nicely gritty look, but a lot of other scenes just look like a made-for-TV movie. Macklin's relationship with his girlfriend, played by Karen Black, is pointless and has an unpleasantly abusive aspect. The ending is the biggest disappointment. It feels hastily assembled and finishes on a jokey note that is very un-Parker.

The Outfit is worth watching, but I wouldn't go out of my way to track it down.

The first oddity is that short, balding Robert Duvall is cast in the Parker role. Now Duvall can play tough, but he just doesn't appear tough (why does he hold his gun in that odd way?), and Parker is certainly described as looking rangy and menacing. The second oddity is that his character is called Earl Macklin instead of Parker. I can't even guess why that change was made. Joe Don Baker plays Macklin's sidekick and he would have been a much better choice for the Parker character.

The story is one that Stark would recycle in Butcher's Moon: the Outfit has killed Macklin's brother in retaliation for he and Earl having robbed a bank a few years previously that was controlled by the Outfit. Macklin goes to the Outfit's boss and demands a payment of 250k as a penalty for killing his brother (such brotherly love). The Outfit refuses, and Macklin and his sidekick begin knocking over Outfit properties until they agree to pay the "fine." They try to double-cross Macklin and that turns out to be a bad idea.

And now a word about the Outfit. The Outfit is a feature of the old Parker novels, and it's one that now feels somewhat dated. To a certain degree it plays the role that SPECTRE did in the James Bond novels. Both are highly organized criminal enterprises with interests in all kinds of criminal activity. The Outfit is essentially the Mafia, only it seems to be run entirely run by WASPy types. In Parker's world, every city has a parallel criminal economy, and it's all run by the Outfit.

The scenes of Macklin knocking over Outfit properties are done very well, and a lot of Stark's terse, muscular dialogue makes it to the screen to great effect. The acting is equally fine, which isn't surprising given that cast is stuffed with veteran character actors, everyone from Elisha Cook to Robert Ryan. Some parts are more uneven. Bruce Surtees is the cinematographer (he shot a lot Clint Eastwood's films) and he gives some scenes a nicely gritty look, but a lot of other scenes just look like a made-for-TV movie. Macklin's relationship with his girlfriend, played by Karen Black, is pointless and has an unpleasantly abusive aspect. The ending is the biggest disappointment. It feels hastily assembled and finishes on a jokey note that is very un-Parker.

The Outfit is worth watching, but I wouldn't go out of my way to track it down.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Book Review: Butcher's Moon (1974) By Richard Stark

In 1962 Donald E. Westlake, writing as Richard Stark, introduced the character of Parker, a professional thief who is as remorseless as he is efficient. This first novel was The Hunter (filmed as Point Blank with Lee Marvin) and it probably marks the beginning of the modern American crime novel. Prior to The Hunter crime novels were largely about detectives and detection, and stories about criminals usually ended with the crooks caught or killed. Stark changed all that. Parker always lives to steal another day, and he usually leaves a high body count in his wake. And Parker's no Robin Hood; he steals for himself, and if his accomplices are caught or killed that's their bad luck. Parker isn't just hardboiled, he's frozen in carbonite.

One of the chief pleasures of the Parker novels is the plotting. The stories begin at a dead run and then rarely pause for a breath. Parker and his confederates always plan their heists to the last detail, but then something usually goes awry, and Parker ends up avoiding pursuers or doing some pursuing himself. Sometimes he's doing both at the same time. Despite the breathlessness of the plotting, Stark takes care to add some depth and shading to even minor characters, and he can also add humour here and there; in Butcher's Moon, in the middle of a casino heist, two thieves and the casino operator they're robbing suddenly have a ridiculously passionate discussion about health food and fitness.

It's easy to see the influence Stark had on Elmore Leonard, who began his crime writing career just as Stark was winding down the Parker series. Leonard's plots are also about criminal plots that go off the rails, his heroes are often Parker-like, and Leonard's novels always feature humorous, parenthetical moments. And Leonard in turn has influenced a host of other writers and filmmakers (step forward Mr Tarantino). The character of Parker has also been reborn in Lee Child's Jack Reacher thrillers. The Reacher character is definitely on the right side of the law, but his ruthlessness, his skill, his matter-of-fact approach to danger is pure Parker.

In Butcher's Moon, Parker and his frequent partner Alan Grofield travel to a small city in Ohio to reclaim a stash of money they'd hidden there years before. The money is missing and the finger of blame points towards the head of the local crime syndicate. Parker wants his money and applies pressure to the crime boss, but that ends with Grofield being wounded and captured. Parker then assembles a gang of thieves he's worked with in previous novels and they begin an all-out assault on the syndicate's men and businesses. Things get very exciting and very bloody.

Butcher's Moon, written in 1974, marks the end of "old" Parker. In 1999 Stark resumed writing Parker novels and these very definitely gave us a "new" Parker. New Parker is even better than old Parker. Old Parker novels occasionally suffer from stilted tough-guy dialogue, and the depiction of women can be summed up by the fact that they're usually referred to as "broads" or "dames." Also, the plots of some of the old Parkers sometimes bordered on the farfetched, straying out of the crime genre and into action/adventure. Butcher's Moon suffers a bit from this last problem, but in other respects it's a bridge to new Parker. The dialogue is free of cliche and there's no blatant sexism.

New Parker began with the aptly-titled Comeback, and in all respects Stark's writing is better. The plots are more unpredictable and believable, the dialogue is leaner and devoid of cliches, and Parker is made more human, but no less implacable and lethal, by the addition of a steady girlfriend. The best of the new Parkers is Breakout, which features both a prison escape and a heist. I suspect Stark brought back Parker because he felt a bit miffed that Leonard, Child, and others were getting rich in a genre that was largely his creation.

Check out the trailer for Point Blank below, but be warned that while it's superb, it makes significant departures from the book.

One of the chief pleasures of the Parker novels is the plotting. The stories begin at a dead run and then rarely pause for a breath. Parker and his confederates always plan their heists to the last detail, but then something usually goes awry, and Parker ends up avoiding pursuers or doing some pursuing himself. Sometimes he's doing both at the same time. Despite the breathlessness of the plotting, Stark takes care to add some depth and shading to even minor characters, and he can also add humour here and there; in Butcher's Moon, in the middle of a casino heist, two thieves and the casino operator they're robbing suddenly have a ridiculously passionate discussion about health food and fitness.

It's easy to see the influence Stark had on Elmore Leonard, who began his crime writing career just as Stark was winding down the Parker series. Leonard's plots are also about criminal plots that go off the rails, his heroes are often Parker-like, and Leonard's novels always feature humorous, parenthetical moments. And Leonard in turn has influenced a host of other writers and filmmakers (step forward Mr Tarantino). The character of Parker has also been reborn in Lee Child's Jack Reacher thrillers. The Reacher character is definitely on the right side of the law, but his ruthlessness, his skill, his matter-of-fact approach to danger is pure Parker.

In Butcher's Moon, Parker and his frequent partner Alan Grofield travel to a small city in Ohio to reclaim a stash of money they'd hidden there years before. The money is missing and the finger of blame points towards the head of the local crime syndicate. Parker wants his money and applies pressure to the crime boss, but that ends with Grofield being wounded and captured. Parker then assembles a gang of thieves he's worked with in previous novels and they begin an all-out assault on the syndicate's men and businesses. Things get very exciting and very bloody.

Butcher's Moon, written in 1974, marks the end of "old" Parker. In 1999 Stark resumed writing Parker novels and these very definitely gave us a "new" Parker. New Parker is even better than old Parker. Old Parker novels occasionally suffer from stilted tough-guy dialogue, and the depiction of women can be summed up by the fact that they're usually referred to as "broads" or "dames." Also, the plots of some of the old Parkers sometimes bordered on the farfetched, straying out of the crime genre and into action/adventure. Butcher's Moon suffers a bit from this last problem, but in other respects it's a bridge to new Parker. The dialogue is free of cliche and there's no blatant sexism.

New Parker began with the aptly-titled Comeback, and in all respects Stark's writing is better. The plots are more unpredictable and believable, the dialogue is leaner and devoid of cliches, and Parker is made more human, but no less implacable and lethal, by the addition of a steady girlfriend. The best of the new Parkers is Breakout, which features both a prison escape and a heist. I suspect Stark brought back Parker because he felt a bit miffed that Leonard, Child, and others were getting rich in a genre that was largely his creation.

Check out the trailer for Point Blank below, but be warned that while it's superb, it makes significant departures from the book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)