Here's who I really want to see this film: Quentin Tarantino and Steven Spielberg. The pair should be strapped into chairs, have their eyelids locked open a la Clockwork Orange, and be made to watch it over and over again until they begin screaming, "I get it! I get it!" The former will have learned that the history of American slavery is not a suitable subject for an action-comedy wankfest, and the latter will realize that a historical film about a grave and serious subject doesn't need to be buried under a pyroclastic flow of sentimentality, melodrama, bombastic music, and overripe production design.

12 Years a Slave is a harrowing true story about Solomon Northrup, a free black man living in Saratoga, New York, in 1841 who is kidnapped and sold into slavery in the South. Northup's story (the film is based on the book he wrote about his experiences) is filled with the historical tropes of American slavery--beatings, separation of families, sexual exploitation, rape, lynchings, and backbreaking labour. All of these crimes have been shown before in films about the pre-Civil War South, so don't be expecting to see something new on the subject of slavery. What makes this film so exceptional is its artistry.

Director Steve McQueen has made the brilliant decision to let the facts speak for themselves. The horrors of slavery are presented without undue emphasis or sentimentality. One scene early in the film shows a black mother being sold and thereby permanently separated from her two small children. It would have been easy to go the Spielberg route and turn the scene into something overblown, like an aria from a tragic opera, but McQueen lets the scene play out sans editorial comment, and it becomes all the more ghastly because it's underplayed. The director's restraint is even more evident at the end of the film when a single scene encompasses both Northrup's salvation as his white Northern friends find him and secure his release, and his parting from Patsey, a female slave who's the tormented concubine of her demented owner, played brilliantly by Michael Fassbender. Any other director would have dragged this sequence out for maximum emotional value, but McQueen positively whips through the scene and captures that bolt from the blue feeling Northup must have experienced. McQueen clearly made the decision that the facts of Northrup's enslavement needed no dressing up.

This is also a beautifully shot film. There's no sweeping camerawork, no overuse of filters to create gaudy sunrises and sunsets, there's just one beautifully composed shot after another. Like the script and the direction, the cinematography isn't trying to manipulate our emotions or hammer home plot points. And the same can be said for the music by Hans Zimmer, which sometimes has a jarring, almost science fiction-y sound to it that emphasizes Northrup's transition from freedom to slavery. The actors are all top-notch, although Brad Pitt's cameo felt more like a movie star doing a cameo than an actor tackling a role. And yet more credit for McQueen for his choice of Lupita Nyong'o as Patsey. She's beautiful, but most directors would have chosen a more conventionally attractive actor for the role, and they certainly would have played up her looks to explain why she becomes her owner's sex slave. So, needless to say, this is my choice for best film of the year, and I might have to rate it as one of the best films of the last ten years. That it should have to face off against trash like American Hustle and The Wolf of Wall Street for Oscars is a tragedy of another kind.

Showing posts with label Quentin Tarantino. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Quentin Tarantino. Show all posts

Thursday, February 6, 2014

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Film Review: Drum (1976)

Django Unchained, which I reviewed back in January, is a bad film. Drum, which I caught on Netflix last night, is also a bad film. Both films are about slavery in the Old South but in some significant ways Django stands out as much the worse film. Drum has no pretensions to being anything other than a middling budget exploitation picture. The story revolves around slavery, but what's on sale here are copious amounts of violence and female nudity. The title character, played by boxer Ken Norton with a woodenness that sends splinters shooting off the screen, is a slave raised in a New Orleans whorehouse. His mother Mariana, who is white, owns the bordello, but has never told Drum that he's her son. Drum thinks his mother is Mariana's faithful maid. Drum catches the attention of DeMarigny, a Frenchman who's, well, let's just say he's a triple-coated villain, a man so low he stole his French accent from Pepe Le Pew. DeMarigny wants to use Drum as a fighter against other slaves, but Drum is a reluctant scrapper. After a variety of brawls and murders, Drum must flee New Orleans. Mariana sells him to Hammond, a slave owner who has a plantation on which he does nothing but breed slaves. More nudity and violence ensues, climaxing with a slave rebellion that leaves almost everyone, white and black, dead. Roll credits.

As mentioned, Drum is an exploitation picture and on that basis it earns a blue ribbon. There's nary a scene that doesn't feature sex, violence or nudity. What's rather amazing is that the script manages to pull in all the exploitation elements without interrupting the narrative flow. Everything about Drum is lurid and over-the-top, but the script is a solid, logical piece of writing. The scriptwriter also earns points for the dialogue, which is pulpy to the max and not afraid to sound ridiculous. Some credit also has to go to the cast. Pros like Warren Oates, John Colicos, Yaphet Kotto and Royal Dano tackle their lurid characters with gusto and almost manage to compensate for "actors" like Ken Norton. Lastly, the film deserves credit for an ending that adheres to reality (the blacks are wiped out) and also allows for some ambiguity. Hammond (Warren Oates) is in most respects a thorough villain, but a brief scene earlier in the film involving the beating of a slave shows us that a part of him (a very small part) is conflicted about treating humans as chattel. In the last scene in the film Hammond chooses to let Drum escape rather than gun him down as he would have every reason to do as white slave owner. It's a surprising ending for what's otherwise a pretty conventional film.

The strengths, relatively speaking, of Drum do a good job of highlighting even further the deficiencies of Django Unchaned. Tarantino's script is a mess: uneven in tone, overlong, and stuffed with gratuitous scenes and dialogue. Drum's script isn't going to win any awards, but it's model of efficient storytelling, and when the word "nigger" is used it's done in a natural, honest way. When Tarantino writes "nigger" in his scripts I always get the feeling he does it to prove how naughty he is. An odd thing about Tarantino is that as much as he's a devotee of genre/exploitation pictures, he's also a prude. Quentin is happy to show people being riddled with bullets or saying "nigger" with every breath, but nudity? sex? God forbid! Miscegenation was the primal fear and fantasy of Southern society, but it doesn't exist for Tarantino. The ending of Django stands in stark contrast to that of Drum. In Tarantino's wish-fulfillment fantasy world (see Inglourious Basterds for further evidence) the black hero rides off into the sunset with his white enemies all slain, his girl by his side, and a horse that can dance. Drum runs off into the night with nothing but a look of terror on his face. No prizes for guessing which film is more historically accurate.

I'm not going to say that Drum is a good film, but for the demographic it was intended for it succeeds brilliantly. And if it reminds you in any way of Django Unchained that's because Tarantino seems to havestolen been heavily influenced by elements of Drum. And for optimum viewing pleasure both films should be seen at a drive-in accompanied by your favourite legal/illegal stimulant.

As mentioned, Drum is an exploitation picture and on that basis it earns a blue ribbon. There's nary a scene that doesn't feature sex, violence or nudity. What's rather amazing is that the script manages to pull in all the exploitation elements without interrupting the narrative flow. Everything about Drum is lurid and over-the-top, but the script is a solid, logical piece of writing. The scriptwriter also earns points for the dialogue, which is pulpy to the max and not afraid to sound ridiculous. Some credit also has to go to the cast. Pros like Warren Oates, John Colicos, Yaphet Kotto and Royal Dano tackle their lurid characters with gusto and almost manage to compensate for "actors" like Ken Norton. Lastly, the film deserves credit for an ending that adheres to reality (the blacks are wiped out) and also allows for some ambiguity. Hammond (Warren Oates) is in most respects a thorough villain, but a brief scene earlier in the film involving the beating of a slave shows us that a part of him (a very small part) is conflicted about treating humans as chattel. In the last scene in the film Hammond chooses to let Drum escape rather than gun him down as he would have every reason to do as white slave owner. It's a surprising ending for what's otherwise a pretty conventional film.

The strengths, relatively speaking, of Drum do a good job of highlighting even further the deficiencies of Django Unchaned. Tarantino's script is a mess: uneven in tone, overlong, and stuffed with gratuitous scenes and dialogue. Drum's script isn't going to win any awards, but it's model of efficient storytelling, and when the word "nigger" is used it's done in a natural, honest way. When Tarantino writes "nigger" in his scripts I always get the feeling he does it to prove how naughty he is. An odd thing about Tarantino is that as much as he's a devotee of genre/exploitation pictures, he's also a prude. Quentin is happy to show people being riddled with bullets or saying "nigger" with every breath, but nudity? sex? God forbid! Miscegenation was the primal fear and fantasy of Southern society, but it doesn't exist for Tarantino. The ending of Django stands in stark contrast to that of Drum. In Tarantino's wish-fulfillment fantasy world (see Inglourious Basterds for further evidence) the black hero rides off into the sunset with his white enemies all slain, his girl by his side, and a horse that can dance. Drum runs off into the night with nothing but a look of terror on his face. No prizes for guessing which film is more historically accurate.

I'm not going to say that Drum is a good film, but for the demographic it was intended for it succeeds brilliantly. And if it reminds you in any way of Django Unchained that's because Tarantino seems to have

Friday, January 25, 2013

Film Review: Django Unchained (2012)

Based on Django Unchained, it seems fair to say that Quentin Tarantino isn't interested in making films anymore, or at least not the kind that people have traditionally recognized as films. Django isn't so much a film as it is a loosely stitched together series of moments and bits that are meant to be appreciated by themselves, totally apart from any kind of coherent narrative. The audience for this kind of film? The demographic that delights in discovering and chattering about tropes, meta moments, homages, genre references, and tributes to other films. If that's the kind of film you like Django is an absolute buffet of genre cliches and, dare I say it, tropes. For the rest of us this is a jaw-droppingly bad piece of filmmaking that goes on and on and on. There are so many things wrong with Django it's going to be easier just to narrow it down to a sampling of the things that annoyed me the most:

Talk is way too cheap

Early in his career Tarantino was justifiably praised for his dialogue. If you can be damned with faint praise, it appears that in Quentin's case you can also be damned with too much. He's turned into a scriptwriting windbag. Scene after scene has characters talking at such length it would be more accurate to call this script a Hansard. Not only are most scenes grotesquely overlong, some are completely gratuitous.

It's a western?

Django is supposed to be some kind of tribute/homage to spaghetti westerns, but in truth the story turns out be more of a drawing room comedy of mayhem. The key visual element in any western is the great outdoors. The idea of vast, unpopulated spaces was one of the reasons for the popularity of westerns in small, overpopulated Europe, hence the rise of the spaghetti western. Tarantino has no eye or enthusiasm for shooting outdoors. Just to let us know we're watching a western he has Django and Schultz ride past a herd of buffalo. OK, fine, there's that box ticked. And then several scenes later we see them go past a herd of elk. Oh, right, I almost forgot I was watching a western. That's the extent of the director's enthusiasm for western landscapes. Most of the film takes place in smallish rooms and the tone in the latter half is more blacksploitation than western.

Foghorn Leghorn was a technical advisor on the film

Yes, most of the actors seem to have taken voice lessons from Foghorn Leghorn, especially Leonardo DiCaprio. And Don Johnson gets to play a plantation owner in full Colonel Sanders regalia. This is as subtle as things get in the film.

Guns don't kill people, massive, spectacular blood loss does

If I sit down to watch one of the Saw films or something by Dario Argento I expect and demand buckets of blood. But a western? For no clear reason Tarantino films his shootouts as though they were scenes in a horror movie. When bullets hit flesh in this universe they release a geyser of blood that travels yards. I know, I know, it's a homage to Peckinpah, but he didn't make blood a star in its own right.

Why are there so many empty beds in the Old Actors' Home?

I can answer that: it's because Tarantino dragooned Tom Wopat, Franco Nero, Russ Tamblyn, Lee Horsley, and Bruce Dern into making cameo appearances. Why? So film geeks can play Spot The Former Star. It's a lot like the Where's Waldo books but without the popcorn. These actors don't add anything to the film except a distraction.

A Peculiar Institution

Believe it or not, some critics and Tarantino apologists/fans have been furrowing their brows and saying that Django delivers a strong lesson about the evils of slavery. Well, if you've been living in a cave for the last 100 years or so it might be news that slavery was a bad thing, but for the rest of us it's a yawn-inducing revelation. And Tarantino isn't really interested in any kind of serious look at slavery; his interest in slavery only extends to referencing tawdry exploitation flicks on the subject like Mandingo and Drum.

Miscegenation, please

For someone who worships at the temple of genre films, the nastier and cruder the better, Tarantino proves to be something of a prude. He's happy to show wholesale quantities of graphic violence, but sex and nudity is something he seems uncomfortable with. All of his films are G-rated when it comes to sex. T & A is a big part of all the genres referenced in Django, especially the slave-themed ones, but Tarantino skates right around some obvious opportunities for naked fun. How boring.

Hot Shots: Part Trois

Remember those parody film franchises like Scary Movie and Hot Shots? Tarantino must have decided to honour that genre as well because that's the only explanation for a farcical sequence with Don Johnson and Jonah Hill (yes, Jonah Hill) as members of a Klan-like posse that gets into an argument about headgear. The scene is supposed to be farcical and off-kilter, just like some of the conversations in Pulp Fiction, but it's written and filmed so badly you have to wonder if the Wayans brothers weren't in charge of this part of the film.

White/Star Power

For a film that's supposed to have a strong black power vibe, at the end of the day it's mostly about the white characters. Jamie Foxx as Django gets to shoot a lot of white folks, but it's Christoph Waltz and DiCaprio who get almost all the dialogue, and Waltz's character is very clearly the brains of the outfit.

Draw!

Correct me if I'm wrong, but don't western action sequences have their own particular grammar and tradition? Not in this one. The shootouts owe more to Scarface and John Woo than Sergio Leone. And they're dull. No style, no imagination; Django just draws his gun and mows down scores ofblood bags southerners.

Does Tarantino have a Screen Actors Guild card?

If he does, someone please take it away from him. Quentin makes one of his unfortunate acting appearances towards the end (he gets blowed up real good) and this time he treats us to an Australian accent. Why an Australian accent? Don't ask, because you might also begin to ask what a German bounty hunter is doing in the Old West.

There's one good thing in Django and it's Samuel L. Jackson. He plays an elderly, evil house servant and what little wit and energy the film has is provided by him. But that's always the case with Jackson, isn't it?

Talk is way too cheap

Early in his career Tarantino was justifiably praised for his dialogue. If you can be damned with faint praise, it appears that in Quentin's case you can also be damned with too much. He's turned into a scriptwriting windbag. Scene after scene has characters talking at such length it would be more accurate to call this script a Hansard. Not only are most scenes grotesquely overlong, some are completely gratuitous.

It's a western?

Django is supposed to be some kind of tribute/homage to spaghetti westerns, but in truth the story turns out be more of a drawing room comedy of mayhem. The key visual element in any western is the great outdoors. The idea of vast, unpopulated spaces was one of the reasons for the popularity of westerns in small, overpopulated Europe, hence the rise of the spaghetti western. Tarantino has no eye or enthusiasm for shooting outdoors. Just to let us know we're watching a western he has Django and Schultz ride past a herd of buffalo. OK, fine, there's that box ticked. And then several scenes later we see them go past a herd of elk. Oh, right, I almost forgot I was watching a western. That's the extent of the director's enthusiasm for western landscapes. Most of the film takes place in smallish rooms and the tone in the latter half is more blacksploitation than western.

Foghorn Leghorn was a technical advisor on the film

Yes, most of the actors seem to have taken voice lessons from Foghorn Leghorn, especially Leonardo DiCaprio. And Don Johnson gets to play a plantation owner in full Colonel Sanders regalia. This is as subtle as things get in the film.

Guns don't kill people, massive, spectacular blood loss does

If I sit down to watch one of the Saw films or something by Dario Argento I expect and demand buckets of blood. But a western? For no clear reason Tarantino films his shootouts as though they were scenes in a horror movie. When bullets hit flesh in this universe they release a geyser of blood that travels yards. I know, I know, it's a homage to Peckinpah, but he didn't make blood a star in its own right.

Why are there so many empty beds in the Old Actors' Home?

I can answer that: it's because Tarantino dragooned Tom Wopat, Franco Nero, Russ Tamblyn, Lee Horsley, and Bruce Dern into making cameo appearances. Why? So film geeks can play Spot The Former Star. It's a lot like the Where's Waldo books but without the popcorn. These actors don't add anything to the film except a distraction.

A Peculiar Institution

Believe it or not, some critics and Tarantino apologists/fans have been furrowing their brows and saying that Django delivers a strong lesson about the evils of slavery. Well, if you've been living in a cave for the last 100 years or so it might be news that slavery was a bad thing, but for the rest of us it's a yawn-inducing revelation. And Tarantino isn't really interested in any kind of serious look at slavery; his interest in slavery only extends to referencing tawdry exploitation flicks on the subject like Mandingo and Drum.

Miscegenation, please

For someone who worships at the temple of genre films, the nastier and cruder the better, Tarantino proves to be something of a prude. He's happy to show wholesale quantities of graphic violence, but sex and nudity is something he seems uncomfortable with. All of his films are G-rated when it comes to sex. T & A is a big part of all the genres referenced in Django, especially the slave-themed ones, but Tarantino skates right around some obvious opportunities for naked fun. How boring.

Hot Shots: Part Trois

Remember those parody film franchises like Scary Movie and Hot Shots? Tarantino must have decided to honour that genre as well because that's the only explanation for a farcical sequence with Don Johnson and Jonah Hill (yes, Jonah Hill) as members of a Klan-like posse that gets into an argument about headgear. The scene is supposed to be farcical and off-kilter, just like some of the conversations in Pulp Fiction, but it's written and filmed so badly you have to wonder if the Wayans brothers weren't in charge of this part of the film.

White/Star Power

For a film that's supposed to have a strong black power vibe, at the end of the day it's mostly about the white characters. Jamie Foxx as Django gets to shoot a lot of white folks, but it's Christoph Waltz and DiCaprio who get almost all the dialogue, and Waltz's character is very clearly the brains of the outfit.

Draw!

Correct me if I'm wrong, but don't western action sequences have their own particular grammar and tradition? Not in this one. The shootouts owe more to Scarface and John Woo than Sergio Leone. And they're dull. No style, no imagination; Django just draws his gun and mows down scores of

Does Tarantino have a Screen Actors Guild card?

If he does, someone please take it away from him. Quentin makes one of his unfortunate acting appearances towards the end (he gets blowed up real good) and this time he treats us to an Australian accent. Why an Australian accent? Don't ask, because you might also begin to ask what a German bounty hunter is doing in the Old West.

There's one good thing in Django and it's Samuel L. Jackson. He plays an elderly, evil house servant and what little wit and energy the film has is provided by him. But that's always the case with Jackson, isn't it?

Friday, November 2, 2012

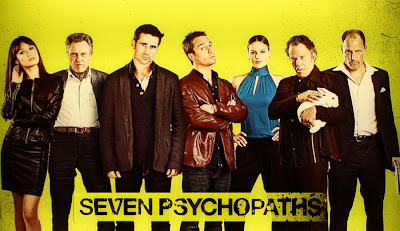

Film Review: Seven Psychopaths (2012)

There's always a danger with rookie film directors that if their first outing is a success, they end up in a creative death spiral of trying to repeat that success. It happened to Quentin Tarantino after Jackie Brown, and it's happened to Martin McDonagh with Seven Psychopaths. His first, and previous, film was In Bruges, which was well-liked by everyone who enjoys dark, quirky, violent films. In Bruges worked because it managed to balance a solid story and excellent acting with some oddball characters and quirky, eccentric moments of violence and humour.

Seven Psychopaths gets the mix all wrong. The first danger signal is that the lead character, played by Colin Farrell, is a scriptwriter in L.A. trying to come up with a story to flesh out the title (Seven Psychopaths) he's dreamed up. With the exception of Fellini's 8 1/2, films about filmmakers struggling with creative problems don't have a great track record, and this one is one of the worst. Farrell's character has a violent title for his script but he doesn't want to write any more stories about evil men with guns doing terrible things. So off the top it looks like this film's going to be a commentary about senseless action movies. If only. Films are made to make money, so of course Seven Psychopaths quickly turns into yet another senseless action movie about evil men blowing holes in people.

McDonagh tries to paper over the ramshackle story (the plot revolves around a fatuous dognapping scheme) with bits and pieces of black comedy, but it all feels half-hearted and poorly imagined. And someone has to declare a moratorium on using Christopher Walken in dark, quirky films. He's now become a parody of himself, and directors trot him out to deliver eccentric dialogue in his own distinctively loopy style as though he's some kind of circus performer. It's like there's a formula for edgy indie films and part of it involves a triple helping of Walken to two parts ironic attitude. Sam Rockwell and Woody Harrelson take the other major roles and they don't do anything we haven't seen from them before. The worst thing about the film, however, is that McDonagh appears to think doubling down on the violence and weirdness represents creativity. The only good thing about the film is that Farrell gets to keep his Irish accent. He always seems to be less of an actor without it.

Seven Psychopaths gets the mix all wrong. The first danger signal is that the lead character, played by Colin Farrell, is a scriptwriter in L.A. trying to come up with a story to flesh out the title (Seven Psychopaths) he's dreamed up. With the exception of Fellini's 8 1/2, films about filmmakers struggling with creative problems don't have a great track record, and this one is one of the worst. Farrell's character has a violent title for his script but he doesn't want to write any more stories about evil men with guns doing terrible things. So off the top it looks like this film's going to be a commentary about senseless action movies. If only. Films are made to make money, so of course Seven Psychopaths quickly turns into yet another senseless action movie about evil men blowing holes in people.

McDonagh tries to paper over the ramshackle story (the plot revolves around a fatuous dognapping scheme) with bits and pieces of black comedy, but it all feels half-hearted and poorly imagined. And someone has to declare a moratorium on using Christopher Walken in dark, quirky films. He's now become a parody of himself, and directors trot him out to deliver eccentric dialogue in his own distinctively loopy style as though he's some kind of circus performer. It's like there's a formula for edgy indie films and part of it involves a triple helping of Walken to two parts ironic attitude. Sam Rockwell and Woody Harrelson take the other major roles and they don't do anything we haven't seen from them before. The worst thing about the film, however, is that McDonagh appears to think doubling down on the violence and weirdness represents creativity. The only good thing about the film is that Farrell gets to keep his Irish accent. He always seems to be less of an actor without it.

Monday, September 26, 2011

Book Review: Butcher's Moon (1974) By Richard Stark

In 1962 Donald E. Westlake, writing as Richard Stark, introduced the character of Parker, a professional thief who is as remorseless as he is efficient. This first novel was The Hunter (filmed as Point Blank with Lee Marvin) and it probably marks the beginning of the modern American crime novel. Prior to The Hunter crime novels were largely about detectives and detection, and stories about criminals usually ended with the crooks caught or killed. Stark changed all that. Parker always lives to steal another day, and he usually leaves a high body count in his wake. And Parker's no Robin Hood; he steals for himself, and if his accomplices are caught or killed that's their bad luck. Parker isn't just hardboiled, he's frozen in carbonite.

One of the chief pleasures of the Parker novels is the plotting. The stories begin at a dead run and then rarely pause for a breath. Parker and his confederates always plan their heists to the last detail, but then something usually goes awry, and Parker ends up avoiding pursuers or doing some pursuing himself. Sometimes he's doing both at the same time. Despite the breathlessness of the plotting, Stark takes care to add some depth and shading to even minor characters, and he can also add humour here and there; in Butcher's Moon, in the middle of a casino heist, two thieves and the casino operator they're robbing suddenly have a ridiculously passionate discussion about health food and fitness.

It's easy to see the influence Stark had on Elmore Leonard, who began his crime writing career just as Stark was winding down the Parker series. Leonard's plots are also about criminal plots that go off the rails, his heroes are often Parker-like, and Leonard's novels always feature humorous, parenthetical moments. And Leonard in turn has influenced a host of other writers and filmmakers (step forward Mr Tarantino). The character of Parker has also been reborn in Lee Child's Jack Reacher thrillers. The Reacher character is definitely on the right side of the law, but his ruthlessness, his skill, his matter-of-fact approach to danger is pure Parker.

In Butcher's Moon, Parker and his frequent partner Alan Grofield travel to a small city in Ohio to reclaim a stash of money they'd hidden there years before. The money is missing and the finger of blame points towards the head of the local crime syndicate. Parker wants his money and applies pressure to the crime boss, but that ends with Grofield being wounded and captured. Parker then assembles a gang of thieves he's worked with in previous novels and they begin an all-out assault on the syndicate's men and businesses. Things get very exciting and very bloody.

Butcher's Moon, written in 1974, marks the end of "old" Parker. In 1999 Stark resumed writing Parker novels and these very definitely gave us a "new" Parker. New Parker is even better than old Parker. Old Parker novels occasionally suffer from stilted tough-guy dialogue, and the depiction of women can be summed up by the fact that they're usually referred to as "broads" or "dames." Also, the plots of some of the old Parkers sometimes bordered on the farfetched, straying out of the crime genre and into action/adventure. Butcher's Moon suffers a bit from this last problem, but in other respects it's a bridge to new Parker. The dialogue is free of cliche and there's no blatant sexism.

New Parker began with the aptly-titled Comeback, and in all respects Stark's writing is better. The plots are more unpredictable and believable, the dialogue is leaner and devoid of cliches, and Parker is made more human, but no less implacable and lethal, by the addition of a steady girlfriend. The best of the new Parkers is Breakout, which features both a prison escape and a heist. I suspect Stark brought back Parker because he felt a bit miffed that Leonard, Child, and others were getting rich in a genre that was largely his creation.

Check out the trailer for Point Blank below, but be warned that while it's superb, it makes significant departures from the book.

One of the chief pleasures of the Parker novels is the plotting. The stories begin at a dead run and then rarely pause for a breath. Parker and his confederates always plan their heists to the last detail, but then something usually goes awry, and Parker ends up avoiding pursuers or doing some pursuing himself. Sometimes he's doing both at the same time. Despite the breathlessness of the plotting, Stark takes care to add some depth and shading to even minor characters, and he can also add humour here and there; in Butcher's Moon, in the middle of a casino heist, two thieves and the casino operator they're robbing suddenly have a ridiculously passionate discussion about health food and fitness.

It's easy to see the influence Stark had on Elmore Leonard, who began his crime writing career just as Stark was winding down the Parker series. Leonard's plots are also about criminal plots that go off the rails, his heroes are often Parker-like, and Leonard's novels always feature humorous, parenthetical moments. And Leonard in turn has influenced a host of other writers and filmmakers (step forward Mr Tarantino). The character of Parker has also been reborn in Lee Child's Jack Reacher thrillers. The Reacher character is definitely on the right side of the law, but his ruthlessness, his skill, his matter-of-fact approach to danger is pure Parker.

In Butcher's Moon, Parker and his frequent partner Alan Grofield travel to a small city in Ohio to reclaim a stash of money they'd hidden there years before. The money is missing and the finger of blame points towards the head of the local crime syndicate. Parker wants his money and applies pressure to the crime boss, but that ends with Grofield being wounded and captured. Parker then assembles a gang of thieves he's worked with in previous novels and they begin an all-out assault on the syndicate's men and businesses. Things get very exciting and very bloody.

Butcher's Moon, written in 1974, marks the end of "old" Parker. In 1999 Stark resumed writing Parker novels and these very definitely gave us a "new" Parker. New Parker is even better than old Parker. Old Parker novels occasionally suffer from stilted tough-guy dialogue, and the depiction of women can be summed up by the fact that they're usually referred to as "broads" or "dames." Also, the plots of some of the old Parkers sometimes bordered on the farfetched, straying out of the crime genre and into action/adventure. Butcher's Moon suffers a bit from this last problem, but in other respects it's a bridge to new Parker. The dialogue is free of cliche and there's no blatant sexism.

New Parker began with the aptly-titled Comeback, and in all respects Stark's writing is better. The plots are more unpredictable and believable, the dialogue is leaner and devoid of cliches, and Parker is made more human, but no less implacable and lethal, by the addition of a steady girlfriend. The best of the new Parkers is Breakout, which features both a prison escape and a heist. I suspect Stark brought back Parker because he felt a bit miffed that Leonard, Child, and others were getting rich in a genre that was largely his creation.

Check out the trailer for Point Blank below, but be warned that while it's superb, it makes significant departures from the book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)