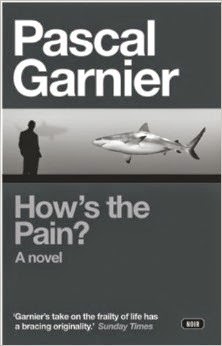

In my experience French crime writers can be divided between the relentlessly quirky (Fred Vargas, Alex Lemaitre, Pierre Magnan) and the relentlessly ferocious (Dominique Manotti, Sebastian Japrisot, Jean Patrick Manchette, Georges Simenon). The first group specializes in oddball characters and wildly improbable plots. Team number two can also craft some truly Byzantine plots, but what really makes them special is their merciless examination of the fears, beliefs and motivations of their characters. A writer who favours quirky characters is usually also a sentimentalist at heart. Sentimentality isn't in the vocabulary of the second group. They have ice in their hearts and take a vivisectionist's approach to the human psyche, showing no mercy when it comes to throwing their characters into harrowing situations and horrible fates. Pascal Garnier is the definitive ferocious writer.

How's the Pain? is about an elderly hitman, Simon, who's dying of cancer and has one last job to finish. He meets a simple-minded young man, Bernard, in a town in southern France andd hires him as a driver. Bernard is a Labrador retriever in human form: loyal, friendly, ready for anything, and eternally optimistic. Simon is a shark. He kills without remorse and for any reason. This sounds like a humorous, odd couple pairing, but it's anything but. Bernard immediately complicates what's left of Simon's life by befriending a slatternly single mother and bringing her along for the ride. The story takes a succession of left turns, usually involving death, and the ending is as bleak and sudden as a car accident. Moon in a Dead Eye strays out of the crime genre into surrealism. The setting is a newly-built trailer park in the south of France that caters to retirees. Two retired couples, a caretaker, and two single women are the only occupants of the park. What happens to them is best described as a series of psychological breakdowns of a surrealist nature that ends with multiple deaths and a forest fire. The novel's title is probably a nod to a famous scene in the film Un Chien Andalou, the surrealist classic by Luis Bunuel.

Both novels take a cold, pitiless look at aging and mortality. The elderly characters in these stories are chased to their graves by dementia, illness, sadness, and regret for things they did or didn't do in their lives. Garnier seems determined to remind his readers that not only is Death waiting for us all, but he's also in a bad mood and wants to take it out on us. As is usual in French crime fiction, the middle classes take a thorough kicking. This is particularly so in Moon in a Dead Eye, which charts the fragile, tenuous nature of bougeois dreams and respectability. In this way it's an interesting companion piece to two other Bunuel films, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Phantom of Liberty. The inhabitants of the Les Conviviales trailer park descend into different kinds of madness, all laced with the blackest of humor. It's this quality that makes Moon in a Dead Eye more of a surrealist novel than a piece of crime fiction, although major crimes do take place.

Garnier's novels are so short they almost qualify as novellas, but his writing is so psychologically acute, his observations so sharp, he seems to pack more intellectual content into his novels than most "serious" writers manage in novels five times as long. Garnier's far from being your average crime fiction author, but if you like Jean Patrick Manchette, or you're just a fan of scorched-earth prose, then Garnier's your man.

Friday, February 13, 2015

Monday, February 9, 2015

Film Review: The Border (1982)

For some people Jack Nicholson is a grandstanding actor who has spent most of his career chewing up the scenery in films like The Shining, Batman and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Nicholson does have that side to his acting personality, but there's also a more buttoned-version, and that's what we get in this unfairly neglected film about corrupt Border Patrol agents in El Paso, Texas.

Nicholson is Charlie Smith, an Immigration and Naturalization agent in L.A. who's pushed into joining the Border Patrol by his wife, Marcy, played by Valerie Perrine. Marcy wants the better things in life, especially a house, and argues that a new job in El Paso with the Border Patrol will give that to them. In parallel with the Smiths move to El Paso, we see Maria, a young Mexican woman, heading across Mexico towards the U.S. border with her infant child and teenage brother. They've been uprooted by an earthquake that's destroyed their village. Charlie hasn't been in the job long before he realizes that his job is essentially pointless; he grabs illegal immigrants as they sneak across the border, processes them, sends them back, and then catches them all over again the next day or the next week. He also learns that some of his fellow agents (Harvey Keitel and Warren Oates) are being bribed by the head of a local smuggling ring. Charlie figures he might as well make some extra money out of this pointless process and he agrees to go on the take. That ends almost immediately when he sees that the smugglers expect the agents to kill their competition. Maria is caught crossing the border and the smugglers steal her baby to sell it on the black market. Charlie befriends Maria and the film becomes a thriller as he tries to find her child and not get killed by smugglers and corrupt Border Patrol agents.

One startling aspect to The Border from a 2015 perspective is its sympathy for illegal immigrants. In these days of Mexican drug cartels and hot button topics like amnesty for illegal immigrants, it's hard to remember that Mexican immigrants were once viewed sympathetically. The film wears its heart on it sleeve by portraying all the American characters, excepting Charlie, as complete bastards. The Border Patrol is corrupt and uncaring, and the wives of Charlie and the character played by Harvey Keitel are shrieking, whining monsters of consumerism. With the exception of one oily smuggler, the Mexican are shown in a rather better light. The director, Tony Richardson, even manages to find a visual metaphor for this divide between the nationalities. Scenes on the Mexican side of the border show water being used to baptize babies, for washing up, and for drinking. On the U.S. side it's akin to a toy; something that only has value when it's used in water beds (Marcy's purchase of an expensive one precipitates Charlie's turn to the dark side) or pools. And then, of course, there's the river that divides the two countries and that features in the final shot of the film.

The Border still works well as a thriller, makes good use of its Texas locations, and reminds you that Jack Nicholson could turn in a subtle, restrained performance when he wanted to. What hasn't aged well is the treatment of the female characters. Maria is saintly and mostly silent, and the American wives are just out and out harridans, full stop. The job of proving that American culture is shallow is given to them and it's a festival of sexism and misogyny. And any film that has Harvey Keitel and Warren Oates acting together deserves your full attention.

Nicholson is Charlie Smith, an Immigration and Naturalization agent in L.A. who's pushed into joining the Border Patrol by his wife, Marcy, played by Valerie Perrine. Marcy wants the better things in life, especially a house, and argues that a new job in El Paso with the Border Patrol will give that to them. In parallel with the Smiths move to El Paso, we see Maria, a young Mexican woman, heading across Mexico towards the U.S. border with her infant child and teenage brother. They've been uprooted by an earthquake that's destroyed their village. Charlie hasn't been in the job long before he realizes that his job is essentially pointless; he grabs illegal immigrants as they sneak across the border, processes them, sends them back, and then catches them all over again the next day or the next week. He also learns that some of his fellow agents (Harvey Keitel and Warren Oates) are being bribed by the head of a local smuggling ring. Charlie figures he might as well make some extra money out of this pointless process and he agrees to go on the take. That ends almost immediately when he sees that the smugglers expect the agents to kill their competition. Maria is caught crossing the border and the smugglers steal her baby to sell it on the black market. Charlie befriends Maria and the film becomes a thriller as he tries to find her child and not get killed by smugglers and corrupt Border Patrol agents.

One startling aspect to The Border from a 2015 perspective is its sympathy for illegal immigrants. In these days of Mexican drug cartels and hot button topics like amnesty for illegal immigrants, it's hard to remember that Mexican immigrants were once viewed sympathetically. The film wears its heart on it sleeve by portraying all the American characters, excepting Charlie, as complete bastards. The Border Patrol is corrupt and uncaring, and the wives of Charlie and the character played by Harvey Keitel are shrieking, whining monsters of consumerism. With the exception of one oily smuggler, the Mexican are shown in a rather better light. The director, Tony Richardson, even manages to find a visual metaphor for this divide between the nationalities. Scenes on the Mexican side of the border show water being used to baptize babies, for washing up, and for drinking. On the U.S. side it's akin to a toy; something that only has value when it's used in water beds (Marcy's purchase of an expensive one precipitates Charlie's turn to the dark side) or pools. And then, of course, there's the river that divides the two countries and that features in the final shot of the film.

The Border still works well as a thriller, makes good use of its Texas locations, and reminds you that Jack Nicholson could turn in a subtle, restrained performance when he wanted to. What hasn't aged well is the treatment of the female characters. Maria is saintly and mostly silent, and the American wives are just out and out harridans, full stop. The job of proving that American culture is shallow is given to them and it's a festival of sexism and misogyny. And any film that has Harvey Keitel and Warren Oates acting together deserves your full attention.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015

Film Review: American Sniper (2014)

Is American Sniper as morally blind, jingoistic and lacking in political context as a host of commentators and critics have described it? Yes. Yes it is. Most of the critical flak has been aimed at director Clint Eastwood, but I'd say scriptwriter Jason Hall and producer/star Bradley Cooper deserve more of the blame.

Eastwood's direction here ranges from efficient to perfunctory to downright lazy, but I'm calling out Hall and Cooper for a jaw-droppingly bad script that feels as though it was crafted by a committee comprised of PR people for the NRA and the Tea Party. The script does such a thorough job of ducking the hard and nasty truths about Chris Kyle and the war in Iraq that it should qualify as a fantasy film. Kyle's ghostwritten autobiography and subsequent revelations about his post-war life made it clear that he was a racist, a sociopath, and a congenital liar who fantasized about killing civilians. These qualities probably helped make him grade A material for the Navy SEALS, but why would a scriptwriter and producer go so far out of their way to whitewash a character who was, to put it mildly, halfway to being a serial killer? The script also cuts and pastes the historical record in order to suggest that Iraq was behind the 9/11 attacks. I'd say this kind of revisionism, and the film's fawning celebration of good ole boy machismo, is a calculated and cynical strategy to appeal to a specific and considerable American demographic; namely the kind of people who flesh out the ranks of the Tea Party; holiday in Branson, MO; fill the stands at NASCAR races; attend gun shows on Saturdays and pack the pews of megachurches on Sundays. This is the audience this film is tailor-made for. American Sniper glorifies, even beatifies, the values and myths they hold dear and does it with a rigorous disregard for the thorny inconveniences of irony, historical accuracy, psychological insight, and the moral and political consequences of military actions.

American Sniper also continues a tradition of mainstream Hollywood films portraying wars purely in terms of their effect on American soldiers and civilians. Vietnam films, even politically liberal ones such as Coming Home, had nothing to say about the two million Vietnamese killed in the war. The Hurt Locker, another film about the Iraq war, is very similar in tone and subject matter to American Sniper and also shares its lack of interest in the war's impact on Iraqis. If your only knowledge of Iraq came from those two films you'd be left with the idea that Iraq was entirely filled with terrorists and their civilian supporters. The combination of two wars and brutal economic sanctions between those wars have led to the deaths, by some estimates, of a million Iraqis and the displacement of millions more. According to Hollywood's moral accounting, none of that counts for anything compared to the temporary psychological stresses suffered by one soldier, Chris Kyle, and his wife.

Looked at purely from a cinematic perspective, Eastwood's direction is robotic. The plentiful action sequences are visually dull and lack tension, the boot camp section is an afterthought, and the scenes that show Kyle suffering from PTSD make it look like it's a condition akin to having a few too many coffees. I think at some point in pre-production everyone decided this best way to approach this film was to be non-judgmental and let the facts (according to Chris Kyle) speak for themselves. That's translated into a dull, witless, nasty film that might have worked better if it had paraphrased the title of an earlier, better Eastwood film: how does White Sniper, Black Heart sound?

Eastwood's direction here ranges from efficient to perfunctory to downright lazy, but I'm calling out Hall and Cooper for a jaw-droppingly bad script that feels as though it was crafted by a committee comprised of PR people for the NRA and the Tea Party. The script does such a thorough job of ducking the hard and nasty truths about Chris Kyle and the war in Iraq that it should qualify as a fantasy film. Kyle's ghostwritten autobiography and subsequent revelations about his post-war life made it clear that he was a racist, a sociopath, and a congenital liar who fantasized about killing civilians. These qualities probably helped make him grade A material for the Navy SEALS, but why would a scriptwriter and producer go so far out of their way to whitewash a character who was, to put it mildly, halfway to being a serial killer? The script also cuts and pastes the historical record in order to suggest that Iraq was behind the 9/11 attacks. I'd say this kind of revisionism, and the film's fawning celebration of good ole boy machismo, is a calculated and cynical strategy to appeal to a specific and considerable American demographic; namely the kind of people who flesh out the ranks of the Tea Party; holiday in Branson, MO; fill the stands at NASCAR races; attend gun shows on Saturdays and pack the pews of megachurches on Sundays. This is the audience this film is tailor-made for. American Sniper glorifies, even beatifies, the values and myths they hold dear and does it with a rigorous disregard for the thorny inconveniences of irony, historical accuracy, psychological insight, and the moral and political consequences of military actions.

American Sniper also continues a tradition of mainstream Hollywood films portraying wars purely in terms of their effect on American soldiers and civilians. Vietnam films, even politically liberal ones such as Coming Home, had nothing to say about the two million Vietnamese killed in the war. The Hurt Locker, another film about the Iraq war, is very similar in tone and subject matter to American Sniper and also shares its lack of interest in the war's impact on Iraqis. If your only knowledge of Iraq came from those two films you'd be left with the idea that Iraq was entirely filled with terrorists and their civilian supporters. The combination of two wars and brutal economic sanctions between those wars have led to the deaths, by some estimates, of a million Iraqis and the displacement of millions more. According to Hollywood's moral accounting, none of that counts for anything compared to the temporary psychological stresses suffered by one soldier, Chris Kyle, and his wife.

Looked at purely from a cinematic perspective, Eastwood's direction is robotic. The plentiful action sequences are visually dull and lack tension, the boot camp section is an afterthought, and the scenes that show Kyle suffering from PTSD make it look like it's a condition akin to having a few too many coffees. I think at some point in pre-production everyone decided this best way to approach this film was to be non-judgmental and let the facts (according to Chris Kyle) speak for themselves. That's translated into a dull, witless, nasty film that might have worked better if it had paraphrased the title of an earlier, better Eastwood film: how does White Sniper, Black Heart sound?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)