One of the big complaints leveled against films like Transformers and Cowboys & Aliens is that so much intelligence and artistry goes into programming the computers that spit out the CG images, none appears to be left for the script. The result, many critics say, is that we're left with compelling special effects sequences attached to a lot of bad dialogue and clunky plots. Not like in the good old days when Hollywood cared about plot, character and dialogue, right? Uh, no.

In the pre-Star Wars days the word studios and filmmakers used instead of CGI or special effects was "spectacle." And spectacle meant you were going to get hordes of extras, exotic locales, and big, long, complicated action sequences. Lawrence of Arabia is probably the definitive spectacle film in the same way that Avatar is the ultimate (for now) special effects film. Grand Prix was one of the big spectacle films of its time.

I have only previously seen Grand Prix on TV, and that was in b&w and over twenty years ago. After just seeing it on DVD on a big screen I'd have to say it counts as the Transformers of its day. The spectacle part is truly spectacular. The story follows four different drivers over the course of one Formula One season, and along the way John Frankenheimer, the director, stages four races that are definitive in their excellence. If you set out today to film a Formula One race, even using all the latest technology, it's impossible to imagine doing a better job than Frankenheimer did. The pacing, the camerawork, the editing, it's all perfect.

But now we come to the other half of the equation: that part of the script that's not devoted to vroom-vroom. It's godawful. Away from the track our drivers, played by James Garner, Yves Montand, Brian Bedford, and Antonio Sabato, find themselves in romantic entanglements with three women, played by Jessica Walter, Eva Marie Saint and Francoise Hardy. Note the disparity in numbers. This is because Garner and Bedford find themselves fighting for the affections of Jessica Walter. Each romantic sub-plot is worse than the next, and they go on and on and on. Montand and Eva Marie Saint have the dullest extramarital affair in history, and Sabato and Hardy, neither of whom appear to speak English, have a romance that feels like a role-playing exercise in an ESL class.

Not only is the romantic stuff rancid, it's not even filmed with any technical competence. Some of the interior sequences are harshly lit, and camera shadows are plainly visible in more than a few shots. I strongly suspect that Frankenheimer, exhausted or otherwise occupied by planning the race sequences, handed off these scenes to a second unit director. At least I'd like to believe that, because Frankenheimer was normally just as good at directing non-action sequences. So next time you hear someone say that CGI is killing storytelling, bear in mind that Hollywood has always sacrificed story for spectacle. Most of the toga epics of the 1950s and early '60s (think Cleopatra, Ben-Hur) were just as empty-headed and spectacular as The Green Lantern or Battle Los Angeles.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Book Review: Never the Bride (2006) by Paul Magrs

Here's the deal: if you're going to have a ridiculous, fantastical premise for your novel, you'd better follow through with some highly imaginative storytelling or a lot of humour to let us know that you appreciate how ludicrous your basic concept is. Paul Magrs does neither. His heroine is Brenda, the original Bride of Frankenstein, who now operates a B & B in Whitby, England, where, with the help of her friend Effie, she battles supernatural baddies. Apparently, Whitby is a gateway to Hell so all kinds of shifty, dangerous characters reside in the neighborhood.

Magrs has a fun premise to build a comic, Terry Pratchett-esque story around, but he settles instead for a bland, cozy mystery with a dollop of horror. What's worse is that he structures his novel in a clumsy, episodic fashion. This gives the book the feeling of being a first-draft treatment for a TV series rather than a properly planned novel. Magrs can write, it's just that his plotting doesn't come close to matching his prose. Magrs has written for Dr. Who in the past, and that's what this novel comes across as: a Dr. Who story minus the doctor and minus the imagination.

Magrs has a fun premise to build a comic, Terry Pratchett-esque story around, but he settles instead for a bland, cozy mystery with a dollop of horror. What's worse is that he structures his novel in a clumsy, episodic fashion. This gives the book the feeling of being a first-draft treatment for a TV series rather than a properly planned novel. Magrs can write, it's just that his plotting doesn't come close to matching his prose. Magrs has written for Dr. Who in the past, and that's what this novel comes across as: a Dr. Who story minus the doctor and minus the imagination.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

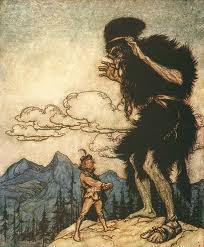

Film Review: Trollhunter (2010)

Yes, this one takes its style and structure from the Blair Witch playbook, but the trolls make all the difference. The filmmakers haven't tried to make their trolls look plausible or somehow alien; these trolls look like something from an illustration in a kids' book of fairy tales: they have multiple heads, cartoonishly bulbous noses, a galumphing walk, and, true to legend, they like to lurk under bridges. These trolls are also very, very big, and the director, Andre Ovredal, deserves credit for making them more menacing than that critter in Cloverfield, despite the fact that trolls are, well, silly.

The plot, such as it is, has some eager college kids deciding to make a documentary about Hans, a man they suspect is a bear poacher. This early part of the story isn't setup very well, but it serves to get us to the trolls. Hans, it turns out, is actually a trollhunter employed by the Norwegian government to keep trolls in check. The government wants to keep trolls hush-hush, but Hans is tired of the secrecy and lets himself be filmed. What follows is something of a nature documentary as Hans talks matter-of-factly about the natural history of trolls. We also see Hans at his work, which consists of tracking down rogue trolls and killing them with light. Trolls, as all Norwegian kids know, die if exposed to light, or, in this case, a battery of lights mounted on a truck.

The climax of the film takes place on a snowy plateau where Hans faces off against a 200-foot tall mountain troll. It's at this point, if not before, that you realize this film looks as good or better than most Hollywood creature features, and that's with a budget of only $3m. All is not perfect with Trollhunter: the college kids are superfluous, and the film cries out for a bit more humour (these are effing trolls!), but it's certainly a lot of fun. In fact, I'd be willing to watch a Trollhunter 2 as long as they keep the budget low.

The plot, such as it is, has some eager college kids deciding to make a documentary about Hans, a man they suspect is a bear poacher. This early part of the story isn't setup very well, but it serves to get us to the trolls. Hans, it turns out, is actually a trollhunter employed by the Norwegian government to keep trolls in check. The government wants to keep trolls hush-hush, but Hans is tired of the secrecy and lets himself be filmed. What follows is something of a nature documentary as Hans talks matter-of-factly about the natural history of trolls. We also see Hans at his work, which consists of tracking down rogue trolls and killing them with light. Trolls, as all Norwegian kids know, die if exposed to light, or, in this case, a battery of lights mounted on a truck.

The climax of the film takes place on a snowy plateau where Hans faces off against a 200-foot tall mountain troll. It's at this point, if not before, that you realize this film looks as good or better than most Hollywood creature features, and that's with a budget of only $3m. All is not perfect with Trollhunter: the college kids are superfluous, and the film cries out for a bit more humour (these are effing trolls!), but it's certainly a lot of fun. In fact, I'd be willing to watch a Trollhunter 2 as long as they keep the budget low.

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Book Review: The Chateau (1961) by William Maxwell

There are literary novels, and then there are Literary Novels. The Chateau is very definitely the latter. It follows, very consciously, the literary path trod by Henry James with his portraits of middle-class Americans encountering the charms and pitfalls of Europe. In this case, we follow Harold and Barbara Rhodes of New York as they visit France in 1948. In James' novels The American and The Portrait of a Lady, the American characters travel to Europe and experience the expected culture clashes, but also become involved in dramatic plots revolving around love and marriage.

Maxwell does not make the Rhodes' jump through any dramatic hoops, choosing instead to show them coping with the difficulties of new social relationships. The Rhodes' arrive in a France that is still just recovering from the war. They begin their four month trip with an extended stay at a small chateau in the Loire Valley. The chateau, owned by Mlle. Vienot, is run as a guesthouse, and Harold and Barbara soon find themselves in a series of new friendships and awkward social entanglements with Vienot's guests and relatives. The action later moves to the south of France, and then Paris, but the Rhodes' remain involved with the people they first met at the chateau.

Maxwell takes an acute look at the social anxieties of the Rhodes, as well as their emotional and psychological reactions to France, Paris, and the pleasures and pains of travel itself. On this level the novel works quite well as a unique insight into the way travel (as opposed to tourism) can be both psychologically upsetting and liberating. The Rhodes' have a short, but blissful, sojourn on the Riviera and Maxwell captures the intensity of the experience through this remark of Harold's at the end of the stay: "I feel the way I ought to have felt at seventeen and didn't."

Where Maxwell is less successful is with his main characters. For the purposes of this kind of novel Harold and Barbara have to be somewhat innocent and naive, which is fine, but they're also rather flat and colourless. This is a bit surprising given that the French characters, even some of the minor ones, come across as complex and fully-rounded. The Rhodes', by comparison, have characteristics but no character. They have, for example, quite an interest in opera and theatre, and yet nothing about them seems artistic, and nothing we learn about their backgrounds make it seem like they'd be culture vultures. At times it feels as though Maxwell made them opera and theatre buffs just to give the Rhodes somewhere to go in the evenings.

Where Maxwell differs most from James is on the prose front. James was famous for a baroque, nuanced style that people either found brilliant or maddening. Maxwell has a leaner, more direct style, and leavens his story with a lot more humour than James ever did. And in the last section of the novel Maxwell even takes a stab at deconstructing his own novel, with a reader (we assume) interrogating the author as to what happened to the various characters after the "end" of the story.

On the whole The Chateau works best as a look at the tensions and rewards of travel. Maxwell's prose is a pleasure, but it also has to be said that there are some self-consciously literary asides and flourishes that are quite distracting. Maxwell was the fiction editor at The New Yorker from the 1940s to the '70s, and at times I got the feeling that this novel was as much about impressing his peers as it was about Harold and Barbara Rhodes.

Maxwell does not make the Rhodes' jump through any dramatic hoops, choosing instead to show them coping with the difficulties of new social relationships. The Rhodes' arrive in a France that is still just recovering from the war. They begin their four month trip with an extended stay at a small chateau in the Loire Valley. The chateau, owned by Mlle. Vienot, is run as a guesthouse, and Harold and Barbara soon find themselves in a series of new friendships and awkward social entanglements with Vienot's guests and relatives. The action later moves to the south of France, and then Paris, but the Rhodes' remain involved with the people they first met at the chateau.

Maxwell takes an acute look at the social anxieties of the Rhodes, as well as their emotional and psychological reactions to France, Paris, and the pleasures and pains of travel itself. On this level the novel works quite well as a unique insight into the way travel (as opposed to tourism) can be both psychologically upsetting and liberating. The Rhodes' have a short, but blissful, sojourn on the Riviera and Maxwell captures the intensity of the experience through this remark of Harold's at the end of the stay: "I feel the way I ought to have felt at seventeen and didn't."

Where Maxwell is less successful is with his main characters. For the purposes of this kind of novel Harold and Barbara have to be somewhat innocent and naive, which is fine, but they're also rather flat and colourless. This is a bit surprising given that the French characters, even some of the minor ones, come across as complex and fully-rounded. The Rhodes', by comparison, have characteristics but no character. They have, for example, quite an interest in opera and theatre, and yet nothing about them seems artistic, and nothing we learn about their backgrounds make it seem like they'd be culture vultures. At times it feels as though Maxwell made them opera and theatre buffs just to give the Rhodes somewhere to go in the evenings.

Where Maxwell differs most from James is on the prose front. James was famous for a baroque, nuanced style that people either found brilliant or maddening. Maxwell has a leaner, more direct style, and leavens his story with a lot more humour than James ever did. And in the last section of the novel Maxwell even takes a stab at deconstructing his own novel, with a reader (we assume) interrogating the author as to what happened to the various characters after the "end" of the story.

On the whole The Chateau works best as a look at the tensions and rewards of travel. Maxwell's prose is a pleasure, but it also has to be said that there are some self-consciously literary asides and flourishes that are quite distracting. Maxwell was the fiction editor at The New Yorker from the 1940s to the '70s, and at times I got the feeling that this novel was as much about impressing his peers as it was about Harold and Barbara Rhodes.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Film Review: Rise of the Planet of the Apes

| |

| San Francisco's charms had a powerful effect on Caesar. |

One big problem is the plot, which plods forward like a beginner's exercise in scriptwriting: scientist tests anti-Alzheimer's drug on chimp A; drug works; scientist adopts chimp A's infant; infant chimp becomes brilliant thanks to drug; teenage chimp does something bad; chimp goes to ape prison; chimp leads mass escape from ape prison; and so on and so on. There are some tenuous sub-plots, but basically all this film does is make us watch a CGI chimp (Caesar) do cute and clever things up until it's time to put him in prison. From that point the film becomes the simian version of The Great Escape. The plot throws no surprises or twists at us, and the finale is a real letdown. The TV ads would have you believe the escaped and newly intelligent apes get medieval on San Francisco's ass. Sadly, such is not the case. It seems the studio was determined to get a PG-13 rating and so the violence is kept to a bare minimum. There's a lot of noise and property damage, but not much else.

What's most lacking in Rise is wit and humor. I saw this with a full audience and no one laughed or even giggled. The script doesn't even try to have fun with its basically outlandish concept; it's as though the writers had orders from PETA that animal cruelty and experiments on animals are not a fit subject for levity. And as for social and political commentary, there's not a drop. There's an interesting angle to this in that the 1968 film made much mention of evolution. This film doesn't, and while there's no particular reason it should, one wonders if the political climate in the U.S. had a chilling effect on the writers. It seems to me there should have been a scene with Caesar encountering a Michele Bachmann-type creationist, but, hey, I'm only interested in being entertained.

The actors aren't normally bland performers, but in this film they are. James Franco mails in an earnest scientist performance of the kind usually seen in 1950s sci-fi films; Freida Pinto smiles and frowns on cue; and Brian Cox as Kommandant of Stalag Ape stands around wondering why the studio paid extra for him when any random member of Actor's Equity could have done just as good a job at a tenth the cost. The director, Rupert Wyatt, has only one other feature under his belt, and it was, of course, an escape from prison film. Considering how big the budget was on this film, I imagine the studio kept the inexperienced Wyatt on a very short leash, which probably helps explain the film's resolute dullness. The special effects? They're OK, but there's nothing to match them in the script.

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Film Review: Chamber of Death (2007)

|

| Melanie Laurent |

Like The Silence of the Lambs, Chamber of Death is about a killer with a very pervy hobby, but it's also about a kidnapping scheme that goes horribly awry, a dark secret from the past, a petty crime that escalates into murder, and a love affair. In short, this film offers triple the plot of Silence, plus all the requisite tension, horror and drama.

Melanie Laurent, most well known for Inglorious Basterds, stars as Lucie, a detective and single mother of infant twins who's just recently joined the Dunkirk police. A young girl is found murdered and Lucie and her partner Pierre (Eric Caravaca) take the lead in the investigation. The girl appears to have been killed in a ritual manner, but the detectives soon find out that she was kidnapped for ransom. What they don't know is that the ransom payment was botched when two men on a late night drunken joyride struck and killed the girl's father, who was carrying two million Euros to a drop-off. The two men have the loot, but soon have a falling out. Another girl is kidnapped and Lucie and Pierre are racing against the clock to find her.

I won't try to describe all the twist and turns the plot takes, but the dense, twisty nature of the story is one of this film's main pleasures. The director, Alfred Lot, does an amazing job of juggling multiple storylines, and in the middle of this complicated cat-and-mouse thriller he manages to shoehorn in a sweet and believable romance between Lucie and Pierre. He also takes time to give some personality to even the most minor of characters.

The acting is uniformly excellent. Laurent is both appealing and believably tough. She's a bit like a French Sandra Bullock. Special mention goes to Gilles Lellouche who plays one of the men who steal the ransom money. His role is that of a decent man whose life takes one terrible turn, and Lellouche does an excellent job showing his horror and desperation. Lellouche is currently starring in Point Blank (my review here), which is an absolutely kick-ass thriller.

A lot of the credit for Chamber of Death has to go to Franck Thilliez, the co-scriptwriter and author of the novel the script is based on. Thilliez has written more than a few crime novels, but none of them, it seems, have been translated into English. If you go looking for this film take note that it's sometimes titled Melody's Smile. The trailer for the film that I've posted below is, unfortunately, in French only.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Book Review: The Calligrapher's Secret (2011) by Rafik Schami

|

| Rafik Schami |

In this year of the Arab Spring, there's no better guide to the discontents, the tensions, and the psychology of the Arab world than the novels of Rafik Schami. Schami, an Arab-Christian, fled his native Syria in 1971 for Germany. After working in menial jobs he got his degree in chemistry and began working in the chemical industry. In the early '80s he became a full-time writer, writing in German. Since then he's won virtually every German literary prize there is, but only a handful of his novels have been translated into English. That's a tragedy because Schami has to rank as one of the world's great novelists.

Schami's previous novel, The Dark Side of Love (my review here), was a multi-generational saga about forbidden love and clan feuds that covered Syrian history from the early 1900s to 1970. It was a brilliant effort, filled with dozens of memorable characters, a plot that skipped back and forth across the decades, and a breathless mix of tragedy, violence and earthy humour.

The Calligrapher's Secret is almost a scaled-down version of The Dark Side of Love. The story is set in Damascus from 1947-58 and tells the tale of how the calligrapher of the title loses his wife, Noura, to his apprentice Salman. Although this novel doesn't have an epic scope, Schami has the epic ambition to try and explain what it is that keeps the Arab world stuck with one foot in the modern world and the other a thousand years in the past. In Schami's view the problem is that Arabs are unwilling to accept change on a personal or cultural level.

Hamid Farsi, the calligrapher of the title, has the ambition to reform Arabic so that it becomes a more modern language, a language that can be used for more than just poety and religious writings. Naturally enough, Farsi faces opposition from religious fanatics who don't believe that the language of the Koran can be altered in any way, and conservative politicians who can only contemplate change that takes place at a glacial pace. What makes Farsi a tragic figure is that as much as he's a radical in his professional life, in his private life he is cursed with all the sexism and misogyny of the most traditional Arab male. He marries the beautiful Noura while she's still a teenager and treats her like dirt from the word go. This drives Noura into the arms of Salman, and it's this event that brings about Hamid's ultimate downfall.

This bare bones synopsis only gives a hint of the plots within plots in this novel. Schami structures his novels like folktales, in which even the most minor of events or characters can have a profound influence on the plot, and people can wander in and out of the story almost at will. And Schami loves creating characters. Even the most minor of figures is given a backstory, and Schami often tells us what happened to these people long after they've had any influence on the plot. The main characters are superb, particularly Farsi who is largely despicable, but is wholly believable and, to a degree, pitiable.

The only misstep Schami makes is to squeeze much of Farsi's story into the last quarter of the book. By that point we have quite a hate on for him and the most likable characters, Noura and Salman, have left the scene for good. This almost makes this last section of the book feel like an appendix rather than an organic part of the novel, but it's really only the most minor of flaws. Here's hoping that more of Schami's novels are made available in English.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Book Review: Bell' Antonio (1949) by Vitaliano Brancati

|

| Poster for the film of Bell' Antonio |

The central character is Antonio Magnano, a young man so handsome, so beautiful, women are poleaxed with lust simply by looking at him. Antonio is the only child of an upper middle-class couple from Catania in Sicily, and when he returns home in 1934 after spending several years in Rome, his father, Alfio, hopes that the social connections he made with politically important people in the Fascist government will help the family's fortunes. Things seem to pay off in spades when a marriage is arranged for Antonio with Barbara Puglisi, the beautiful daughter of one of Catania's most notable families. Three years into the marriage rumors start to circulate that Antonio isn't quite the virile creature everyone assumed he was, and from this point things start to go pear-shaped for Antonio and the Magnanos.

The first third of the novel has a comic tone as Brancati gives us scathing portraits of Fascist politicos and stuffed shirt Sicilian bourgeoisie. The star character here is Alfio, a bellowing, blustering, boastful exemplar of Sicilian machismo. Alfio lives for family honour and pride, and when the Magnano name starts to be dragged through the mud, his reactions are both hilarious and, by the end of the novel, pitiable. And Alfio is only one of several striking characters Brancati creates. Antonio's Uncle Gildo, a disillusioned priest, is almost as memorable, as is Antonio's best friend, Edoardo.

Brancati's skill at characterization is matched by his fluid, natural way with dialogue. As I read the novel I found I was hearing the dialogue rather than just reading it; I could imagine particular Italian actors reciting the words I was reading. It's no wonder Brancati had success as a screenwriter.

The last third of the novel has a darker tone as WW II sweeps over Sicily, and Catania is reduced to rubble and penury. It's here that Brancati makes explicit the point of his novel, which is that the middle class obsession with honour, social standing, political opportunism, machismo, and family pride meant that a blind eye was turned to the rise of Fascism and Italy's disastrous march to war. And even though Bell' Antonio ends on a down note, Brancati's earthy, robust writing style make his novel a memorably pleasurable experience.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Film Review: L'appartement (1996)

The problem with watching Alfred Hitchcock's films is that they leave you wanting to see another and another, to savour his unique and playful blend of romance, tension and intrigue. Unfortunately Hitch has gone to the Bates Motel in the sky, and no one has really proven to be his equal.

L'appartement is the closest to being a "new" Hitchcock film that I've ever come across. The director, Gilles Mimouni, makes the connection to Hitchcock clear from the beginning with a lush, romantic soundtrack (courtesy of Peter Chase) that immediately recalls Vertigo. Also like Hitch, Mimouni uses sweeping camerawork and a rich colour palette to heighten the eccentric nature of his story.

Ah, the plot. Well, in the interest of not revealing too much I'll just say that Max, played by Vincent Cassel, thinks he catches a glimpse of Lisa (Monica Bellucci), the love of his life who seemingly vanished two years previously. Max has just become engaged and is due to fly to Tokyo for an important business trip, but he decides to put everything on hold to track down Lisa. Naturally, not everything is as it appears and the story, filled with flashbacks and unexpected plot twists, becomes a romantic mystery and a thriller.

Looked at as a whole the plot verges on the nonsensical, but then so do many of Hitchcock's films. Half the fun and purpose of Hitchcock's films is to see what happens to ordinary people when they're caught in an extraordinary series of events. And where Hitchcock liked to play with the language of film, Mimouni focuses on creating a series of overripe, romantic interiors that are stars on their own right. In fact, you could almost call this a film about apartments, as each of the several featured in the story are given a distinct and arresting look. And even Paris, which doesn't need much help to look mysterious and romantic, is made to look lusher and more delectable than the real thing.

During the final section of the film, as the loose ends are being tied up and various mysteries are revealed and solved, you'll be amazed at the cunning of the plot. You'll also want to immediately re-watch it to understand how it all fits together. The only real flaw in the film is that Max is forced to make some unlikely life choices in order to keep the plot moving along, but that's a minor quibble. Call this one Hitchcock's last great film.

Related posts:

Film Review: Malena

L'appartement is the closest to being a "new" Hitchcock film that I've ever come across. The director, Gilles Mimouni, makes the connection to Hitchcock clear from the beginning with a lush, romantic soundtrack (courtesy of Peter Chase) that immediately recalls Vertigo. Also like Hitch, Mimouni uses sweeping camerawork and a rich colour palette to heighten the eccentric nature of his story.

Ah, the plot. Well, in the interest of not revealing too much I'll just say that Max, played by Vincent Cassel, thinks he catches a glimpse of Lisa (Monica Bellucci), the love of his life who seemingly vanished two years previously. Max has just become engaged and is due to fly to Tokyo for an important business trip, but he decides to put everything on hold to track down Lisa. Naturally, not everything is as it appears and the story, filled with flashbacks and unexpected plot twists, becomes a romantic mystery and a thriller.

Looked at as a whole the plot verges on the nonsensical, but then so do many of Hitchcock's films. Half the fun and purpose of Hitchcock's films is to see what happens to ordinary people when they're caught in an extraordinary series of events. And where Hitchcock liked to play with the language of film, Mimouni focuses on creating a series of overripe, romantic interiors that are stars on their own right. In fact, you could almost call this a film about apartments, as each of the several featured in the story are given a distinct and arresting look. And even Paris, which doesn't need much help to look mysterious and romantic, is made to look lusher and more delectable than the real thing.

During the final section of the film, as the loose ends are being tied up and various mysteries are revealed and solved, you'll be amazed at the cunning of the plot. You'll also want to immediately re-watch it to understand how it all fits together. The only real flaw in the film is that Max is forced to make some unlikely life choices in order to keep the plot moving along, but that's a minor quibble. Call this one Hitchcock's last great film.

Related posts:

Film Review: Malena

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)