In addition to run-of-the-mill critical commentary, films these days are often judged on their attitude towards visible minorities, gender roles, ageism, ethnic or religious stereotyping, and the LGBT community. The sequel to Zoolander, which has yet to be released, has gained the ire of the transgender community, Adam Sandler's western series for Netflix has been attacked by native American groups, and Get Hard with Will Ferrell was criticized for its racial politics. It's no surprise that modern films are under this kind of scrutiny given that until fairly recently filmmakers had no qualms about mocking, vilifying, disparaging or ignoring a wide variety of minority groups. There is, however, still one group that lacks adequate or sensitive representation on screen: the working class.

Working class characters are common enough in films as victims or perpetrators of crime, as comic cutups, sidekicks, army grunts, slackers, or as individuals pole vaulting into a higher tax bracket thanks to pluck and luck and pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. What we almost never see are stories about working class people where the focus, the heart of the drama, is on their actual working lives and their relationship to capitalism. Losing a job is one of the most dramatic and painful things that can happen to a person, but it's rarely presented on film. We sometimes see middle- and upper-middle-class people lose their jobs, but that's usually just the jumping-off point for a feelgood story about "self-discovery" and learning about what "really matters." For people who are paid by the hour, having a permanent job is what really matters.

Two Days, One Night is about a French woman, Sandra, played by Marion Cotillard, who loses her job and then fights to get it back. She works for a small firm that assembles solar panels in the north of France. The job is blue collar, there's no union, and the pay is just adequate to sustain a decent lifestyle for her husband (who also works) and two kids. If she doesn't get her job back the family will probably have to move back into social housing. Sandra lost her job because her co-workers were given a choice: get a 1,000 euro bonus and see Sandra let go or keep Sandra and not get a bonus. A clear majority of the 16 workers voted to take the bonus and say goodbye to Sandra, who had the least seniority. At the urging of her husband and her friend, Sandra goes to the company's owner and asks for another vote. She points out that the vote wasn't fair because the foreman who initiated it led the workers to believe that if Sandra wasn't let go then it would mean someone else going out the door, which wasn't the case at all. Also, the ballot wasn't secret. The owner agrees to another vote, and Sandra has the weekend to try and change the minds of the people who voted against her.

It would have been so easy to make this film overly sentimental, preachy or polemical. What we get is a subtle, nuanced portrayal of working-class life under pressure. Each visit Sandra makes to one of her co-workers is a glimpse into the ambitions and struggles of the average worker. In terms of film dramas, one thousand euros (equal to about $1,500) is a paltry sum. In the real world, and in this film, that money represents school tuition, essential car repairs, debts repaid, a family vacation, home improvements, and so on. These aren't world-shaking issues, except to the people who have to deal with them. What's also shown in these meetings is the empathy some workers have for their fellows. They all acknowledge that Sandra got a raw deal and isn't just a victim of bad luck. They also feel terrible that they've been put in the position of deciding the fate of a co-worker. Without saying so explicitly, all of the workers are disturbed or even horrified that they've been put in the position of deciding the fate of Sandra and her family.

The characters are superbly and efficiently drawn. Sandra is no model worker. She suffers from depression, and it's hinted that this affected her work in the past, which may have made it easier for people to vote her out. And by pleading her case with her co-workers Sandra causes some mini-crises in other households as people argue over whether they're justified, morally and otherwise, in sending her packing. One couple breaks up over the issue, and in the film's most powerful scene, a young worker breaks down in tears of shame and relief when he finds out he'll get a chance to change his vote and keep Sandra at the company. Sandra also suffers during this weekend because she's forced to beg people for her job, knowing full well that she's causing them hardship if she convinces them to change their vote.

The end of the film (SPOILER ALERT!) is a mix of pain and hope. The second vote ends in a draw and so Sandra does lose her job. She isn't, however, crushed by this decision. Her experiences over the weekend have revealed her own strength, and, more importantly, the empathy and solidarity of many of her co-workers. The film ends with Sandra going off to begin the search for a new job, buoyed in spirits (slightly) by what she's learned about herself and her co-workers. It's a bitterly realistic ending, but one that points that fighting for justice in the workplace is both difficult and rewarding and makes for fantastic, if rarely seen, drama.

Tuesday, December 29, 2015

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

Best Books of 2015

|

| An actual photograph of me reading. |

Iron Gustav (1938) by Hans Fallada

Fallada's Alone in Berlin made my list last year, and this one is almost as brilliant. The eponymous character is the owner of a fleet of cabs in pre-WWI Berlin. His "iron" character is what causes the slow and sure destruction of his family and business over the course of the story, which has to be definitive portrait of Germany in the 1920s and early '30s.

Europe in Autumn (2014) by Dave Hutchinson

This alternate reality/SF novel shows a Europe that's dividing and sub-dividing into smaller and smaller states, all of them throwing up more and more border controls. Did I say this was fiction? It's also wholly, exhilaratingly original and ends with the promise of stranger things (and sequels) to come.

Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America (2015) by Jill Leovy

L.A. Times journalist Jill Leovy has been on the crime beat (specifically murder) since 2007, and this book is her answer to the question of why there is so much black on black crime in America. Her reportage on the cops, criminals and hapless bystanders in the city's predominantly black south-central district is never less than fascinating, and her explanation for why the area suffers an unending crime wave is analytically sound and completely fascinating.

Moon in a Dead Eye (2009) by Pascal Garnier

This is a surreal novel in the tradition of Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel. A miscellany of retired French folk live in newly opened retirement/trailer park and spontaneously combust, as it were, into various forms of madness as a forest fire sweeps down on the park. Garnier is a master at peeling back the skin of the middle class to show the scary and weird stuff lying underneath.

The Winshaw Legacy, or What a Carve Up! (1994) by Jonathan Coe

This fictional summation of the Thatcher years in the UK is my book of the year. Coe has several axes to grind, and he does so with LOL humor, diabolical plotting, savage characterization, and, dare I say it, a certain brio (read the book and you'll spot the joke in that last sentence.).

The Cartel (2015) by Don Winslow

What makes this all-encompassing novel about the narcowars in Mexico so compelling is that Winslow gives us fully rounded Mexican characters. This subject area is usually dominated, in dramatic terms, by American characters doing all the heavy lifting (see Sicario). Winslow doesn't let the reader forget that it's Mexicans who suffer most from the cartels' predatory actions.

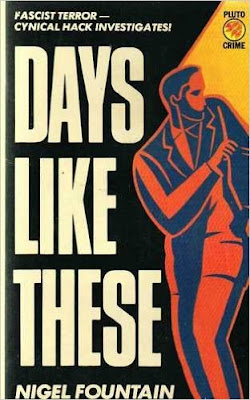

Days Like These (1985) by Nigel Fountain

A shambolic mystery-thriller is usually not a good thing, but in this case it works beautifully. The hero is John Raven, who has a cool name, but is a decidedly uncool hack who lives and works in left-wing political circles. Raven stumbles on a right-wing conspiracy and the fun begins; the fun being a sly and droll look at life on the political edges, played out in grimy bedsits and questionable pubs.

Cuckoo Song (2014) by Frances Hardinge

Fairy lore gets a reboot in this YA novel about a young girl who's been stolen by fairies. These fairies aren't a pack of Tinkerbells. They're dangerous, capricious, and yet not entirely evil. Hardinge's prose, as usual, is brilliant, and her world-building puts her at the top of the class in fantasy writing.

Five Children on the Western Front (2014) by Kate Saunders

Another YA novel, but this one has a title that sounds like a Monty Python skit. It's anything but. Saunders follows E. Nesbit's beloved characters into the First World War and what results is a novel that honours the source material as well as dealing out a harsh anti-war message.

Gun Street Girl (2014) by Adrian McKinty

The fourth D.I. Sean Duffy mystery is as strong as the previous three. The secret to their success is that in Sean Duffy we have a sleuth who actually enjoys (most of the time) what he does. He even likes a lot of his fellow coppers. This is very much against the grain for most contemporary cops who bitch and whine endlessly about their jobs, pausing only briefly to allow their significant others to bitch and whine about police work. McKinty keeps threatening to end this series, but I think he, like Duffy, enjoys the work too much to do that.

Monday, December 21, 2015

Book Review: The Islanders (1998) by Pascal Garnier

This is the fourth Garnier novel for me, and I've come to the conclusion that he's the poltergeist of French literature. Garnier's novels are studies of individuals whose inner demons are kept in check (barely) by the routines, beliefs and ceremonies of middle-class life. Garnier, in his role as a poltergeist, tears apart the delicate web of social respectability and responsibility that keeps his characters on the straight and narrow, and then records what happens to these people when they get off the leash and start barking and biting and killing.

In this novel we have Olivier, a recovering alcoholic, Rodolphe, the world's nastiest blind man, and Jeanne, Olivier's long-ago girlfriend, with whom he shares a murderous secret from their teenage years. Olivier returns to the Paris suburb of Versailles to make funeral arrangements for his deceased mother. Versailles is where he grew up, and it's a place he wholeheartedly detests. Olivier's shocked to find that Jeanne and her brother Rodolphe are living across the hall from his mother's apartment. Olivier and Jeanne haven't seen each other in twenty or so years, but they're almost instantly drawn back to each other. The folie a deux crime for which they were never caught as teenagers was the kidnap and murder of a two-year-old boy. Olivier decides to hit the bottle again, and the bodies start to pile up.

Garnier's plots are spare but smart; he gives his characters a bit of a push in one direction and then, in keeping with the poltergeist metaphor, commences to pinch them, throw things at them, occasionally push them down a long flight of stairs. and otherwise torment them until the worst and truest part of their character is fully revealed. And so it is here. Olivier goes off the wagon for one night and so begins a parade of murders and a trip into madness for the only two characters left standing at the end of the book.

Garnier's artistic inspiration would seem to come from Jean-Paul Sartre's observation in No Exit that "hell is other people." In this novel, as in others by Garnier that I've read, the characters find humanity to be a sorry spectacle, and an excruciating one when having deal one on one with people. A typical Garnier character looks around and describes what he sees and feels using a palette filled with venom-based paints. At times Garnier can go overboard with seeing the world through dystopia-tinted glasses, almost to the point of parody, but his misanthropy is always delivered with a poetic zeal that keeps his novels palatable and energetic rather than dreary and pretentious.

In this novel we have Olivier, a recovering alcoholic, Rodolphe, the world's nastiest blind man, and Jeanne, Olivier's long-ago girlfriend, with whom he shares a murderous secret from their teenage years. Olivier returns to the Paris suburb of Versailles to make funeral arrangements for his deceased mother. Versailles is where he grew up, and it's a place he wholeheartedly detests. Olivier's shocked to find that Jeanne and her brother Rodolphe are living across the hall from his mother's apartment. Olivier and Jeanne haven't seen each other in twenty or so years, but they're almost instantly drawn back to each other. The folie a deux crime for which they were never caught as teenagers was the kidnap and murder of a two-year-old boy. Olivier decides to hit the bottle again, and the bodies start to pile up.

Garnier's plots are spare but smart; he gives his characters a bit of a push in one direction and then, in keeping with the poltergeist metaphor, commences to pinch them, throw things at them, occasionally push them down a long flight of stairs. and otherwise torment them until the worst and truest part of their character is fully revealed. And so it is here. Olivier goes off the wagon for one night and so begins a parade of murders and a trip into madness for the only two characters left standing at the end of the book.

Garnier's artistic inspiration would seem to come from Jean-Paul Sartre's observation in No Exit that "hell is other people." In this novel, as in others by Garnier that I've read, the characters find humanity to be a sorry spectacle, and an excruciating one when having deal one on one with people. A typical Garnier character looks around and describes what he sees and feels using a palette filled with venom-based paints. At times Garnier can go overboard with seeing the world through dystopia-tinted glasses, almost to the point of parody, but his misanthropy is always delivered with a poetic zeal that keeps his novels palatable and energetic rather than dreary and pretentious.

Sunday, December 13, 2015

Film Review: Spectre (2015)

Oh, James, how could you do this to me? I forgave Roger Moore's safari suits and Inspector Gadget gadgets. I overlooked Timothy Dalton's incongruous Royal Shakespeare Company gravitas. And I even tried to pretend that On Her Majesty's Secret Service never happened. But I draw the line at being bored senseless for over two hours.

For this entry in the Bond franchise, 007 is up against Ernst Stavro Blofeld, played by Chrisoph Walz. Blofeld's madcap scheme this time out is to tap into the databases of all the world's leading intelligence agencies, which will enable him to...I'm not actually sure what will happen, but it's probably quite naughty. To combat this dastardly plot Bond has only one option: he must travel from London to Rome to Austria to Morocco in a series of increasingly stylish and acutely-tailored outfits. Once Bond turns up in a white dinner jacket on the dining car of a Moroccan train, we, and SPECTRE, know the game is up. Blofeld has nothing to match Bond's sartorial supremacy, and he even makes the ghastly faux pas of wearing loafers without socks. Seriously, how can a man who's still using Miami Vice's Sonny Crockett as his menswear muse hope to defeat Bond?

To be honest, plotting has never been the strong suit of Bond films. They're a bit like Christmas trees: essentially just scaffolding for lights, decorations and presents. And what we like to find on and under the tree is dry humor, jaw-dropping stunts, one-of-a-kind action set-pieces, outlandish villains, and a bit of very softcore porn. Spectre fails spectacularly at all the traditional Bond elements.

Things get off to a reasonably good start with a fight aboard a helicopter above a packed square in Mexico City, but after that it's all downhill. A car chase in Rome is the definition of perfunctory. Any old episode of Top Gear does something more exciting with cars than this sequence does. Next up is a car/plane chase in the Austrian alps that has some of the ridiculousness of the Roger Moore films, but none of the raised-eyebrow humor. The humor is crucial because without it sequences like this just feel silly. A well-placed gag lets us in on the joke. Bond then proceeds to Blofeld's base inside a huge meteorite crater in the Moroccan desert. This looks promising, I thought, preparing myself for an all-out battle akin to the climax of You Only Live Twice. No such luck. Bond basically walks out of the base whilst shooting some obligingly stationary henchmen ("Shoot me, Mr Bond, shoot me! I'm standing over here! Oof! Gosh, I've been deaded by James Bond 007. My mum will be proud...urghh."). The actual finale happens in London, and it's an unimaginative piece of business that I thought had died out with silent films: Bond's love interest has been tied up in a building that Blofeld has wired to explode, and James must race through the place to find her before time runs out. The only thing missing is a loyal canine to lead James to his girlfriend.

This also has to be the worst Bond film for overall sexiness. Lea Seydoux as Dr Madeleine Swann is, alas, far too young for middle-aged Daniel Craig and they have zero chemistry together. Roger Moore also had problems with the age gap, but his awful puns seemed to take the sting out his love scenes with women half his age. Monica Bellucci makes a brief appearance in the film in what must be the most awkward and creepy sexual episode in any of the Bond films. James backs a seemingly reluctant Bellucci against a wall and disrobes her as though he was unwrapping a Ferrero Rocher chocolate he'd been saving for a special occasion.

I enjoyed Daniel Craig's Casino Royale, but it marked the beginning of an attempt to make Bond more nuanced, human, and believable. It's as though the producers and directors felt slightly ashamed to be associated with a film franchise that had such a sexist and puerile history. But who the hell wants a real world James Bond? If I want that I'll rewatch any of the Jason Bourne films. And as each of Craig's Bond films has come along, his performance have become stiffer, more laconic, and increasingly humorless. Sam Mendes, the director, seems happiest when he's filming lush interiors and Bond's wardrobe. Now, I expect James Bond to dress well, but this film takes it to the next level; so much so that at times he seems to be wearing body art rather than anything made of wool or cotton. The surest sign that the people at the top end of the production team feel that they're too good to be making a Bond film is the name given to Lea Seydoux's character. Madeleine Swann? Really? Is a laboured and witless A la recherche du temps perdu reference supposed to convince us that some very tall foreheads were involved in the making of the film? Sorry, but dragging Marcel Proust into a Bond film is something I can never forgive.

For this entry in the Bond franchise, 007 is up against Ernst Stavro Blofeld, played by Chrisoph Walz. Blofeld's madcap scheme this time out is to tap into the databases of all the world's leading intelligence agencies, which will enable him to...I'm not actually sure what will happen, but it's probably quite naughty. To combat this dastardly plot Bond has only one option: he must travel from London to Rome to Austria to Morocco in a series of increasingly stylish and acutely-tailored outfits. Once Bond turns up in a white dinner jacket on the dining car of a Moroccan train, we, and SPECTRE, know the game is up. Blofeld has nothing to match Bond's sartorial supremacy, and he even makes the ghastly faux pas of wearing loafers without socks. Seriously, how can a man who's still using Miami Vice's Sonny Crockett as his menswear muse hope to defeat Bond?

To be honest, plotting has never been the strong suit of Bond films. They're a bit like Christmas trees: essentially just scaffolding for lights, decorations and presents. And what we like to find on and under the tree is dry humor, jaw-dropping stunts, one-of-a-kind action set-pieces, outlandish villains, and a bit of very softcore porn. Spectre fails spectacularly at all the traditional Bond elements.

Things get off to a reasonably good start with a fight aboard a helicopter above a packed square in Mexico City, but after that it's all downhill. A car chase in Rome is the definition of perfunctory. Any old episode of Top Gear does something more exciting with cars than this sequence does. Next up is a car/plane chase in the Austrian alps that has some of the ridiculousness of the Roger Moore films, but none of the raised-eyebrow humor. The humor is crucial because without it sequences like this just feel silly. A well-placed gag lets us in on the joke. Bond then proceeds to Blofeld's base inside a huge meteorite crater in the Moroccan desert. This looks promising, I thought, preparing myself for an all-out battle akin to the climax of You Only Live Twice. No such luck. Bond basically walks out of the base whilst shooting some obligingly stationary henchmen ("Shoot me, Mr Bond, shoot me! I'm standing over here! Oof! Gosh, I've been deaded by James Bond 007. My mum will be proud...urghh."). The actual finale happens in London, and it's an unimaginative piece of business that I thought had died out with silent films: Bond's love interest has been tied up in a building that Blofeld has wired to explode, and James must race through the place to find her before time runs out. The only thing missing is a loyal canine to lead James to his girlfriend.

This also has to be the worst Bond film for overall sexiness. Lea Seydoux as Dr Madeleine Swann is, alas, far too young for middle-aged Daniel Craig and they have zero chemistry together. Roger Moore also had problems with the age gap, but his awful puns seemed to take the sting out his love scenes with women half his age. Monica Bellucci makes a brief appearance in the film in what must be the most awkward and creepy sexual episode in any of the Bond films. James backs a seemingly reluctant Bellucci against a wall and disrobes her as though he was unwrapping a Ferrero Rocher chocolate he'd been saving for a special occasion.

I enjoyed Daniel Craig's Casino Royale, but it marked the beginning of an attempt to make Bond more nuanced, human, and believable. It's as though the producers and directors felt slightly ashamed to be associated with a film franchise that had such a sexist and puerile history. But who the hell wants a real world James Bond? If I want that I'll rewatch any of the Jason Bourne films. And as each of Craig's Bond films has come along, his performance have become stiffer, more laconic, and increasingly humorless. Sam Mendes, the director, seems happiest when he's filming lush interiors and Bond's wardrobe. Now, I expect James Bond to dress well, but this film takes it to the next level; so much so that at times he seems to be wearing body art rather than anything made of wool or cotton. The surest sign that the people at the top end of the production team feel that they're too good to be making a Bond film is the name given to Lea Seydoux's character. Madeleine Swann? Really? Is a laboured and witless A la recherche du temps perdu reference supposed to convince us that some very tall foreheads were involved in the making of the film? Sorry, but dragging Marcel Proust into a Bond film is something I can never forgive.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

Book Review: The Winshaw Legacy, or What a Carve Up! (1994) by Jonathan Coe

I'm not even going to try and fully outline the plot of this novel except to say that it's a wonderment of deviousness, coincidence, and mystery--Dickens on steroids. In a nutshell, the eponymous Winshaws are the Borgias of post-war Britain. From a family fortune founded on the slave trade, the Winshaws now have their bespoke talons securely fastened in banking, politics, the arms trade, media, and agribusiness. The central character is not a Winshaw, but one Michael Owen, a novelist with emotional baggage to spare. Owen takes a commission to write a history of the Winshaw family. The person underwriting the commission is Tabitha Winshaw, who has been confined in a mental asylum for the past twenty or so years by the other Winshaws. Tabitha is convinced that her brother Lawrence caused the death of her other brother Godfrey during World War Two. And it's Godfrey's death in the war that forms the coiled spring at the centre of a plot that encompasses tragedy, farce, acidic social and political commentary, mass murder, and some of the most polished comic writing this side of P.G. Wodehouse.

The dexterity of the plotting is breathtaking. The story has multiple narrative layers and voices, bags of characters, and sudden tonal shifts that sometimes put the story up on two wheels. It's understating matters to say that Coe is successfully juggling a lot of balls here; he's also keeping a flaming torch, a roaring chainsaw and an angry cat aloft. This is one of those rare novels that's thrilling because we're witnessing a writer making all kinds of high-risk maneuvers that could end very badly. Let me put it this way: how many writers would dare to incorporate both Sid James (star of the Carry On films) and Saddam Hussein (star of various crimes against humanity) as characters in the same novel?

The Winshaws, all nine of them, are mad or bad, and sometimes both. Some reviews that I came across have complained that the presentation of the family lacks subtlety; that the Winshaws are too starkly villainous. Some of the same reviews have also complained that Coe's depiction of political and social issues in Thatcher's Britain is similarly stark and simplistic. These reviewers are missing the point. What Thatcher unleashed in the UK was nothing less than a conservative counter-revolution against a generation of public policies aimed at creating and improving the social welfare state. Thatcher's "reforms" were as brutal and unsubtle as it's possible to be. To talk about those changes in a subtle manner would be to diminish their intent and dumb savagery. If the Winshaws are presented as posh, greedy brutes, it's because those were the foot soldiers in the war to turn back Britain's social and economic clock to somewhere in the Victorian age. And, of course, there are villains, and then there are exceptionally well-written villains. Coe has created a wonderfully diverse group of monsters in the Winshaws, and while they are all determinedly rotten, they are also very entertaining; although none of them goes so far as too stick their genitals in a pig's mouth. No one could possibly believe that...

If I've made The Winshaw Legacy sound like a polemic, believe me, it isn't. Coe is too smart a writer for that. This is first and foremost a novel filled with keenly observed characters, and some powerful episodes describing human suffering of both the physical and psychological variety. Rather amazingly, these tough elements don't jar at all with comic characters and moments that are often wildly funny. So if your taste runs to state-of-the-nation novels (UK division), make this one your choice rather than Martin Amis' Lionel Asbo, which is essentially written from the POV of a Winshaw. And remember that this novel was written in the early 1990s, long before Winshawism, to coin a term, came to fruition under David Cameron, with hearty endorsement by Britain's financial and media elites.

The dexterity of the plotting is breathtaking. The story has multiple narrative layers and voices, bags of characters, and sudden tonal shifts that sometimes put the story up on two wheels. It's understating matters to say that Coe is successfully juggling a lot of balls here; he's also keeping a flaming torch, a roaring chainsaw and an angry cat aloft. This is one of those rare novels that's thrilling because we're witnessing a writer making all kinds of high-risk maneuvers that could end very badly. Let me put it this way: how many writers would dare to incorporate both Sid James (star of the Carry On films) and Saddam Hussein (star of various crimes against humanity) as characters in the same novel?

The Winshaws, all nine of them, are mad or bad, and sometimes both. Some reviews that I came across have complained that the presentation of the family lacks subtlety; that the Winshaws are too starkly villainous. Some of the same reviews have also complained that Coe's depiction of political and social issues in Thatcher's Britain is similarly stark and simplistic. These reviewers are missing the point. What Thatcher unleashed in the UK was nothing less than a conservative counter-revolution against a generation of public policies aimed at creating and improving the social welfare state. Thatcher's "reforms" were as brutal and unsubtle as it's possible to be. To talk about those changes in a subtle manner would be to diminish their intent and dumb savagery. If the Winshaws are presented as posh, greedy brutes, it's because those were the foot soldiers in the war to turn back Britain's social and economic clock to somewhere in the Victorian age. And, of course, there are villains, and then there are exceptionally well-written villains. Coe has created a wonderfully diverse group of monsters in the Winshaws, and while they are all determinedly rotten, they are also very entertaining; although none of them goes so far as too stick their genitals in a pig's mouth. No one could possibly believe that...

If I've made The Winshaw Legacy sound like a polemic, believe me, it isn't. Coe is too smart a writer for that. This is first and foremost a novel filled with keenly observed characters, and some powerful episodes describing human suffering of both the physical and psychological variety. Rather amazingly, these tough elements don't jar at all with comic characters and moments that are often wildly funny. So if your taste runs to state-of-the-nation novels (UK division), make this one your choice rather than Martin Amis' Lionel Asbo, which is essentially written from the POV of a Winshaw. And remember that this novel was written in the early 1990s, long before Winshawism, to coin a term, came to fruition under David Cameron, with hearty endorsement by Britain's financial and media elites.

Monday, December 7, 2015

Book Review: The Radleys (2010) by Matt Haig

Vampires; can't live with 'em, can't live without 'em. Vampirism in literature and film is at once the most tired of genres and also one that still occasionally manages to come up with new and interesting tales to tell. Speaking as someone who works in a big library system, I get to see a lot vampire-lit detritus. The library's shelves are full of vampire romances, vampire manga, vampire thrillers, and lots and lots of vampire teen fiction. I've even come across a Regency-set vampire romance titled Bitten by the Count. Amidst this sanguine avalanche you can still find gems, and The Radleys is one of them.

The Radleys are a British family living an all too normal life in suburbia. Peter is a GP, his wife Helen works for the local government, and their teenage children, son Rowan and daughter Clara, struggle with the social side of school life. And, of course, Helen and Peter are also vampires, albeit abstaining vampires. They are the vegans of the vampire world, unlike many of their peers, and especially Peter's brother Will, who continues to lead the vampire version of the rock star lifestyle. Peter and Helen haven't told their children the family secret, and themselves struggle with staying on the straight and narrow. Both the children suffer from weakness and lassitude from not drinking blood, but put it down to other reasons. The entire family is waist-deep in angst when we meet them. Peter and Helen feel bored and constricted by their non-vampire lives, Clara is nauseous all the time because she's become an actual vegan, and Rowan is experiencing the sheer hell of an unrequited first love. Things take a turn for the very much worse at a nighttime field party when one of Clara's classmates tries to rape her. Clara's vampire side comes bursting out (much to her shock and horror) and her attacker ends up dead. Very dead. The Radley family is now in full crisis mode as Clara's crime has to be covered up, the family secret is revealed to the kids, and Will arrives to "help" the family with their troubles.

Every modern vampire story has to build its own unique mythos, and Matt Haig does an excellent job of putting some clever wrinkles on the standard rules and regs that govern bloodsucker behavior. His vampires are long-lived, but not eternal; can tolerate sunlight, but don't like it; only gain supernatural powers with the consumption of blood; are known to the police, but somewhat tolerated; and can only "create" new vampires by sharing their own blood with their victim. Haig's world-building is admirable, but his real focus is on the psychological pressures facing the Radley family. More specifically, the various flavours of depression afflicting their lives. Both Peter and Helen pine for the freedom and wantonness of life as a predatory vampire. Clara and Rowan are dealing with the usual tortures of teen life, but with the added pressure of longings and anxieties they can't understand.

The vampire component gives this novel its narrative backbone, but it's heart is invested in describing how a family copes with heartbreak, buried secrets, resentment, and fear. The Radleys go through the emotional wringer, and the plot, which is built like a thriller, doesn't give them time to catch their breath. This effectively doubles the story's tension, because it's a race to see what will happen first: will the family be "outed" or will it be destroyed by its own inner tensions. The novel is, by necessity, very dark, but there are moments of humour, and Will is the sort of character who's hugely entertaining as only a truly wicked vampire can be. If The Radleys is ever filmed, the casting call for Will will describe him as a "younger Bill Nighy-type." The only fault with the novel (a very minor one) is that the tone lurches back and forth from YA to adult and back again several times. But I'd still recommend it to both audiences.

The Radleys are a British family living an all too normal life in suburbia. Peter is a GP, his wife Helen works for the local government, and their teenage children, son Rowan and daughter Clara, struggle with the social side of school life. And, of course, Helen and Peter are also vampires, albeit abstaining vampires. They are the vegans of the vampire world, unlike many of their peers, and especially Peter's brother Will, who continues to lead the vampire version of the rock star lifestyle. Peter and Helen haven't told their children the family secret, and themselves struggle with staying on the straight and narrow. Both the children suffer from weakness and lassitude from not drinking blood, but put it down to other reasons. The entire family is waist-deep in angst when we meet them. Peter and Helen feel bored and constricted by their non-vampire lives, Clara is nauseous all the time because she's become an actual vegan, and Rowan is experiencing the sheer hell of an unrequited first love. Things take a turn for the very much worse at a nighttime field party when one of Clara's classmates tries to rape her. Clara's vampire side comes bursting out (much to her shock and horror) and her attacker ends up dead. Very dead. The Radley family is now in full crisis mode as Clara's crime has to be covered up, the family secret is revealed to the kids, and Will arrives to "help" the family with their troubles.

Every modern vampire story has to build its own unique mythos, and Matt Haig does an excellent job of putting some clever wrinkles on the standard rules and regs that govern bloodsucker behavior. His vampires are long-lived, but not eternal; can tolerate sunlight, but don't like it; only gain supernatural powers with the consumption of blood; are known to the police, but somewhat tolerated; and can only "create" new vampires by sharing their own blood with their victim. Haig's world-building is admirable, but his real focus is on the psychological pressures facing the Radley family. More specifically, the various flavours of depression afflicting their lives. Both Peter and Helen pine for the freedom and wantonness of life as a predatory vampire. Clara and Rowan are dealing with the usual tortures of teen life, but with the added pressure of longings and anxieties they can't understand.

The vampire component gives this novel its narrative backbone, but it's heart is invested in describing how a family copes with heartbreak, buried secrets, resentment, and fear. The Radleys go through the emotional wringer, and the plot, which is built like a thriller, doesn't give them time to catch their breath. This effectively doubles the story's tension, because it's a race to see what will happen first: will the family be "outed" or will it be destroyed by its own inner tensions. The novel is, by necessity, very dark, but there are moments of humour, and Will is the sort of character who's hugely entertaining as only a truly wicked vampire can be. If The Radleys is ever filmed, the casting call for Will will describe him as a "younger Bill Nighy-type." The only fault with the novel (a very minor one) is that the tone lurches back and forth from YA to adult and back again several times. But I'd still recommend it to both audiences.

Thursday, December 3, 2015

Bite-Sized Bad Books

These days it seems that for every good book I read, I have to start, and abandon, at least one dud. I can't be bothered to do full reviews of every turkey I come across, so here are three mini-reviews of two books I gave up on, and one that I ended up skim-reading. Consider yourself warned.

Carter & Lovecraft (2015) by Jonathan L. Howard

You wouldn't hire a bespoke tailor to run you up a pair of board shorts and a T-shirt, so why was Howard, the author of the excellent series of Johannes Cabal novels (my review), commissioned to write this tie-in novel for an upcoming TV series? The premise is that a descendant of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft teams up with an ex-NYPD cop to fight supernatural baddies of the Lovecraftian variety. Howard is an excellent writer with an amazing ability to meld steampunk, horror and humour, and he does so with fluid, smart prose and a lot of originality. In Carter & Lovecraft, Howard takes all of his strengths as a writer and tosses them out in favour of a narrative voice that's supposed to sound American, but comes across as second-rate Lee Child. The story is slow, the American setting is poorly realized (Howard is a Brit), the dialogue and banter between the main characters is awkward, and the horror, by the time I abandoned the book at the one-third mark, consisted of one mildly unpleasant death. I hope they paid Howard well, but he should have used a pen name. He has a reputation to protect.

The Color of Smoke (1975) by Menyhert Lakatos

The first English translation of this "epic novel of the Roma" came out in August of this year, and I was intrigued because I've never read anything fictional about the Roma, let alone a novel written by a Roma author. Turns out Lakatos has nothing good to say about his own people. The novel is set just before World War Two in Hungary in a rural community of Roma. Lakatos is unsparing, even savage, in describing the backwardness and brutality of life in this world. In fact, by the halfway point it seemed the book's only purpose was to take vicious swings at the Roma. Lakatos is a good writer but I could only stomach so many descriptions of rural poverty and the abuse of women.

The Road to Little Dribbling (2015) by Bill Bryson

I'll take it on faith that Bill Bryson actually went to the places he describes in this rambling tour around Great Britain. On the other hand it's entirely possible that he sat down in front of his laptop and created this travel book entirely through the generous use of Wikipedia, Google Earth, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and Tripadvisor. And he does, in fact, frequently quote from these sources. Here's the book's formula: Bill travels to a British town or point of interest (Stonehenge, the South Downs, etc.) and lists the local shops, tours a museum and describes its contents, throws in a bit of history culled from the internet, complains about litter/rudeness/various bureaucratic inefficiencies, makes a humorous observation or two, throws in some invented comic dialogue between himself and a local, and then ambles off to his next destination. And he even steals a gag from one of Eddie Izzard's routines. I skim-read my way through this one, marveling that apparently the most successful authors are now allowed to plagiarize their books from the web. It's cheaper than hiring a ghost writer, I suppose.

Carter & Lovecraft (2015) by Jonathan L. Howard

You wouldn't hire a bespoke tailor to run you up a pair of board shorts and a T-shirt, so why was Howard, the author of the excellent series of Johannes Cabal novels (my review), commissioned to write this tie-in novel for an upcoming TV series? The premise is that a descendant of horror writer H.P. Lovecraft teams up with an ex-NYPD cop to fight supernatural baddies of the Lovecraftian variety. Howard is an excellent writer with an amazing ability to meld steampunk, horror and humour, and he does so with fluid, smart prose and a lot of originality. In Carter & Lovecraft, Howard takes all of his strengths as a writer and tosses them out in favour of a narrative voice that's supposed to sound American, but comes across as second-rate Lee Child. The story is slow, the American setting is poorly realized (Howard is a Brit), the dialogue and banter between the main characters is awkward, and the horror, by the time I abandoned the book at the one-third mark, consisted of one mildly unpleasant death. I hope they paid Howard well, but he should have used a pen name. He has a reputation to protect.

The Color of Smoke (1975) by Menyhert Lakatos

The first English translation of this "epic novel of the Roma" came out in August of this year, and I was intrigued because I've never read anything fictional about the Roma, let alone a novel written by a Roma author. Turns out Lakatos has nothing good to say about his own people. The novel is set just before World War Two in Hungary in a rural community of Roma. Lakatos is unsparing, even savage, in describing the backwardness and brutality of life in this world. In fact, by the halfway point it seemed the book's only purpose was to take vicious swings at the Roma. Lakatos is a good writer but I could only stomach so many descriptions of rural poverty and the abuse of women.

The Road to Little Dribbling (2015) by Bill Bryson

I'll take it on faith that Bill Bryson actually went to the places he describes in this rambling tour around Great Britain. On the other hand it's entirely possible that he sat down in front of his laptop and created this travel book entirely through the generous use of Wikipedia, Google Earth, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and Tripadvisor. And he does, in fact, frequently quote from these sources. Here's the book's formula: Bill travels to a British town or point of interest (Stonehenge, the South Downs, etc.) and lists the local shops, tours a museum and describes its contents, throws in a bit of history culled from the internet, complains about litter/rudeness/various bureaucratic inefficiencies, makes a humorous observation or two, throws in some invented comic dialogue between himself and a local, and then ambles off to his next destination. And he even steals a gag from one of Eddie Izzard's routines. I skim-read my way through this one, marveling that apparently the most successful authors are now allowed to plagiarize their books from the web. It's cheaper than hiring a ghost writer, I suppose.

Friday, November 27, 2015

Book review: The Cartel (2015) by Don Winslow

The simplest way to describe The Cartel is to say that it's a panopticon of a novel about the bloody, futile and destructive "war on drugs" waged by the U.S. against the Mexican drug cartels. The central character is Art Keller, a DEA agent who's spent years fighting the cartels, and who has seen and participated in many acts of violence. Keller is almost a burnout case, and the only thing that keeps him going is a deep love of Mexico and a pathological hatred of Adan Barrera, the head of Mexico's strongest cartel. Barrera, like many of the other cartel leaders we meet, wages a constant war to fend off other cartels, stay out of the clutches of the police, and maintain the strength of his organization. The action of the novel is spread over a decade, ending in 2014, and there are simply far too many plots and sub-plots to mention. And that's a good thing. The story masterfully toggles between micro and macro views of the conflict so that every facet of this ongoing tragedy is examined in full.

Winslow's novel is partly didactic in intent. He wants to show his North American readers the sheer extent and endless savagery of this war, particularly its impact on the civilian population. The people who have died in this war aren't limited to those handling drugs and the cops opposing them. The cartels kill to both intimidate and impress, and over the period covered in this novel tens of thousands of Mexicans died at their hands. The actions of the cartels have, to a certain degree, turned Mexico into a failed state. But this isn't really a Mexican problem. The cartels exist to feed American demand, and bought-in-America weaponry does most of the killing south of the border. Winslow does not miss a single political, historical or sociological issue in describing the breadth and horror of this war, and he makes it very clear his sympathies are with the thousands of innocent people brutalized by the cartels and their allies, Mexico's frequently corrupt politicians and policemen.

Although The Cartel often has a docudrama feel, Winslow doesn't neglect his literary duties. Dozens of major and minor characters are sharply described, and even the human monsters, of which there are more than a few, aren't given the cursory treatment. There is much violence, but its brutality is necessary to give us an approximation of how barbaric the "rules" of conflict are; anything ISIS has done has been surpassed years ago by the cartels. It's not a flawless novel. Art has a rather cliche relationship with his superior at the DEA; he's one of those bosses who's always yelling that he's not going to put up with this kind of lone wolf behavior and then does exactly that. And while there are some very strong female characters, there are a few too many fulsome descriptions of women in terms of their sexual desirability. But these are minor issues. What might be the novel's greatest achievement is that it's a major American novel that wrestles with hot button political and social issues. That's a rare event in contemporary American literature, which seems more concerned with the emotional travails of the upper middle classes.

Winslow's novel is partly didactic in intent. He wants to show his North American readers the sheer extent and endless savagery of this war, particularly its impact on the civilian population. The people who have died in this war aren't limited to those handling drugs and the cops opposing them. The cartels kill to both intimidate and impress, and over the period covered in this novel tens of thousands of Mexicans died at their hands. The actions of the cartels have, to a certain degree, turned Mexico into a failed state. But this isn't really a Mexican problem. The cartels exist to feed American demand, and bought-in-America weaponry does most of the killing south of the border. Winslow does not miss a single political, historical or sociological issue in describing the breadth and horror of this war, and he makes it very clear his sympathies are with the thousands of innocent people brutalized by the cartels and their allies, Mexico's frequently corrupt politicians and policemen.

Although The Cartel often has a docudrama feel, Winslow doesn't neglect his literary duties. Dozens of major and minor characters are sharply described, and even the human monsters, of which there are more than a few, aren't given the cursory treatment. There is much violence, but its brutality is necessary to give us an approximation of how barbaric the "rules" of conflict are; anything ISIS has done has been surpassed years ago by the cartels. It's not a flawless novel. Art has a rather cliche relationship with his superior at the DEA; he's one of those bosses who's always yelling that he's not going to put up with this kind of lone wolf behavior and then does exactly that. And while there are some very strong female characters, there are a few too many fulsome descriptions of women in terms of their sexual desirability. But these are minor issues. What might be the novel's greatest achievement is that it's a major American novel that wrestles with hot button political and social issues. That's a rare event in contemporary American literature, which seems more concerned with the emotional travails of the upper middle classes.

Monday, November 23, 2015

Book Review: Vertigo (1954) by Boileau-Narcejac

Yes, this is the novel that Hitchcock's Vertigo was based on, although the original French title was D'entre les Morts. It's been republished with same title as the film, and the good news is that in some ways it's even better than the film. The major difference between the novel and the film is that the novel is set in France, but other than that the film follows the book relatively faithfully. For those of you who've been living in a cave, the story is about a retired police detective (Flavieres) who quit the force after a traumatic incident on a rooftop. Some years later, an old friend he hasn't seen in years looks him up and asks to follow his wife, Madeleine. She is, according to the husband, acting strangely and might be suicidal. Flavieres follows her and saves her from a suicide attempt. Flavieres falls in love with Madeleine, but a few weeks later she throws herself from a church tower, a fatal event witnessed by Flavieres. Four years pass and Flavieres sees a woman he swears is Madeleine. He follows her, woos her, and tries to get her to admit that she is Madeleine. She finally reveals that she played the role of Madeleine as part of a murder plot. Flavieres strangles her and is hauled off to jail. Roll credits.

Hitchcock sensibly made his ending more visual and more dramatic, but what gives the novel extra interest is its Second World War setting. The first part of the novel takes place during the so-called "Phony War" period of 1940, when the French (and British) populations were confident that the war was going to end with a whimper, if it ever managed to get going. The final section of the story is set in late 1944, with France mostly liberated but still demoralized and licking its wounds. Madeleine's deception is meant to find its echo in the Phony War, and the revelation of her role in the plot is, I think, a symbolic reference to those French who collaborated with the Nazis.

Boileau and Narcejac (they were a writing team) had a reason for setting their story during the war, and this added political component gives the novel more depth, more resonance than the film version. Usually writing teams are a recipe for bland prose, but this duo's writing is lively and clever, even stylish. If Vertigo the film is about obsessive love, Vertigo the novel more about betrayal of both the romantic and political variety.

Hitchcock sensibly made his ending more visual and more dramatic, but what gives the novel extra interest is its Second World War setting. The first part of the novel takes place during the so-called "Phony War" period of 1940, when the French (and British) populations were confident that the war was going to end with a whimper, if it ever managed to get going. The final section of the story is set in late 1944, with France mostly liberated but still demoralized and licking its wounds. Madeleine's deception is meant to find its echo in the Phony War, and the revelation of her role in the plot is, I think, a symbolic reference to those French who collaborated with the Nazis.

Boileau and Narcejac (they were a writing team) had a reason for setting their story during the war, and this added political component gives the novel more depth, more resonance than the film version. Usually writing teams are a recipe for bland prose, but this duo's writing is lively and clever, even stylish. If Vertigo the film is about obsessive love, Vertigo the novel more about betrayal of both the romantic and political variety.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Film Review: Sicario (2015)

Major spoilers ahead, so consider yourself warned. First off, I'll acknowledge that Sicario looks great, has an inventive, tension-inducing musical score, and has some action set pieces that are really, really well choreographed. That's where the good news ends. Sicario is also the most badly-plotted film I've seen in a very long time. Some of the Roger Moore James Bond films have more logical and believable plots. The few reviews I've read of Sicario (all laudatory) have apparently been blind to this titanic flaw, apparently fooled by the film's muscular realism and energy. This is a film that skips merrily from one bit of plot inanity to another without catching its breath. And that's not the worst thing about Sicario.

The first scene in the film has FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) leading a raid on a suburban house in Arizona that we assume is a drug den or something of that ilk. She kills one of the men guarding the house and then finds that the ranch bungalow's walls are stuffed with bodies, victims, presumably, of a Mexican drug cartel. Why the cartel would go to all this bother rather than burying people in the surrounding empty desert isn't explained, nor why a cartel henchman would fire at Kate when it's a clear he has no chance to avoid arrest. I'll give the scriptwriter a pass on this one, as the real purpose of the scene is to show us that Kate isn't reluctant to shoot people and that the cartel does some really bad things. Shortly after this raid, Kate is asked to volunteer for a special task force that's targeting the head of one of the Mexican cartels. The task force is led by Matt (Josh Brolin), who commands a small force of ex-Navy Seals(?), and one scary dude named Alejandro played by Benicio del Toro.

From here on, the plot get worse. The film's main action sequence involves the transfer of a prisoner from a jail in Juarez to the American side of the border just a few miles away. It's great cinema, but it has no internal logic. Why ferry the prisoner out of Juarez in a convoy of SUVs (they're ambushed, naturally) when a chopper ride would be easier? Even more ridiculously, the convoy has a cleared road and Mexican police escorts from the border to the prison, but then when they get back to the border the convoy vehicles have to line up with all the other daytrippers going to the U.S. They couldn't get a special lane to themselves for the return journey? Was U.S. Customs afraid the Seals might bring back some undeclared booze? An ambush takes place that's notable for continuing the cinematic trope of henchman being more than willing to give up their lives in a lost cause.

The film's big plot reveal comes past the halfway mark when Matt tells Kate that the only reason she was asked to volunteer for the group is so the CIA could operate on U.S. soil. Evidently the law dictates that the CIA can't operate domestically unless it's allied with a law enforcement agency. So Kate's role is purely symbolic. And why the CIA, you ask? Because they want to wipe out the Mexican cartels and replace them with the Medellin cartel from Colombia. According to Matt, things were better for everyone when only one cartel was in charge of things. All I can say is that a CIA plot this stupid belongs in a Steven Seagal movie.

And that brings me to the film's biggest problem: Kate isn't just a footnote to the CIA's operation, she's a footnote in the film. Take Kate out of the film and absolutely nothing about the story changes. The CIA operation goes as planned, the same people end up dead, and the same final result is achieved. Kate is entirely superfluous. If that wasn't bad enough, the film also goes whole hog on the sexism and misogyny. Kate might be brave, good with guns, and able to kill ruthlessly when necessary, but that's only the script paying lip service to the idea of gender equality. What the story has her mostly doing is fulfilling the traditional role of women in issue-oriented action films; she acts as the scold and nag, the voice of conscience. Poor Emily Blunt has to spend the entirety of the film whining and complaining about "following procedure", and generally being the finger-wagging schoolmarm/mom/wife while Josh Brolin and Benicio del Toro get to act cool, look cool, and talk cool. The film then doubles down on the sexism with some bonus misogyny; to wit, Kate is held down and choked by a corrupt cop (and rescued by Alejandro); shot in her bulletproof vest by Alejandro; and then knocked to the ground and pinned there like an unruly puppy or disobedient child by Matt. What all three scenes have in common is that she's assaulted by these men after she dares to interfere with or criticize their respective schemes. And the film's penultimate scene has Kate crying when Alejandro forces her to sign an incriminating document, because, well, girls always cry under pressure, don't they?

With a 93% approval rating on RottenTomatoes.com, it's clear that Sicario's technical excellence and sharp action sequences have acted as a smokescreen to a more critical examination of its script. Take away Denis Villeneuve's slick direction and Roger Deakins' wonderful cinematography and you have a film that feels like a sequel to Lone Wolf McQuade, a Chuck Norris vehicle from the 1980s. The plot is an unholy mess, its sexual politics are reprehensible, and the politics of the drug trade are ignored in favour of random scenes that reassure we northerners that Mexico is just as big a hellhole as we imagine it to be.

The first scene in the film has FBI agent Kate Macer (Emily Blunt) leading a raid on a suburban house in Arizona that we assume is a drug den or something of that ilk. She kills one of the men guarding the house and then finds that the ranch bungalow's walls are stuffed with bodies, victims, presumably, of a Mexican drug cartel. Why the cartel would go to all this bother rather than burying people in the surrounding empty desert isn't explained, nor why a cartel henchman would fire at Kate when it's a clear he has no chance to avoid arrest. I'll give the scriptwriter a pass on this one, as the real purpose of the scene is to show us that Kate isn't reluctant to shoot people and that the cartel does some really bad things. Shortly after this raid, Kate is asked to volunteer for a special task force that's targeting the head of one of the Mexican cartels. The task force is led by Matt (Josh Brolin), who commands a small force of ex-Navy Seals(?), and one scary dude named Alejandro played by Benicio del Toro.

From here on, the plot get worse. The film's main action sequence involves the transfer of a prisoner from a jail in Juarez to the American side of the border just a few miles away. It's great cinema, but it has no internal logic. Why ferry the prisoner out of Juarez in a convoy of SUVs (they're ambushed, naturally) when a chopper ride would be easier? Even more ridiculously, the convoy has a cleared road and Mexican police escorts from the border to the prison, but then when they get back to the border the convoy vehicles have to line up with all the other daytrippers going to the U.S. They couldn't get a special lane to themselves for the return journey? Was U.S. Customs afraid the Seals might bring back some undeclared booze? An ambush takes place that's notable for continuing the cinematic trope of henchman being more than willing to give up their lives in a lost cause.

The film's big plot reveal comes past the halfway mark when Matt tells Kate that the only reason she was asked to volunteer for the group is so the CIA could operate on U.S. soil. Evidently the law dictates that the CIA can't operate domestically unless it's allied with a law enforcement agency. So Kate's role is purely symbolic. And why the CIA, you ask? Because they want to wipe out the Mexican cartels and replace them with the Medellin cartel from Colombia. According to Matt, things were better for everyone when only one cartel was in charge of things. All I can say is that a CIA plot this stupid belongs in a Steven Seagal movie.

And that brings me to the film's biggest problem: Kate isn't just a footnote to the CIA's operation, she's a footnote in the film. Take Kate out of the film and absolutely nothing about the story changes. The CIA operation goes as planned, the same people end up dead, and the same final result is achieved. Kate is entirely superfluous. If that wasn't bad enough, the film also goes whole hog on the sexism and misogyny. Kate might be brave, good with guns, and able to kill ruthlessly when necessary, but that's only the script paying lip service to the idea of gender equality. What the story has her mostly doing is fulfilling the traditional role of women in issue-oriented action films; she acts as the scold and nag, the voice of conscience. Poor Emily Blunt has to spend the entirety of the film whining and complaining about "following procedure", and generally being the finger-wagging schoolmarm/mom/wife while Josh Brolin and Benicio del Toro get to act cool, look cool, and talk cool. The film then doubles down on the sexism with some bonus misogyny; to wit, Kate is held down and choked by a corrupt cop (and rescued by Alejandro); shot in her bulletproof vest by Alejandro; and then knocked to the ground and pinned there like an unruly puppy or disobedient child by Matt. What all three scenes have in common is that she's assaulted by these men after she dares to interfere with or criticize their respective schemes. And the film's penultimate scene has Kate crying when Alejandro forces her to sign an incriminating document, because, well, girls always cry under pressure, don't they?

With a 93% approval rating on RottenTomatoes.com, it's clear that Sicario's technical excellence and sharp action sequences have acted as a smokescreen to a more critical examination of its script. Take away Denis Villeneuve's slick direction and Roger Deakins' wonderful cinematography and you have a film that feels like a sequel to Lone Wolf McQuade, a Chuck Norris vehicle from the 1980s. The plot is an unholy mess, its sexual politics are reprehensible, and the politics of the drug trade are ignored in favour of random scenes that reassure we northerners that Mexico is just as big a hellhole as we imagine it to be.

Friday, October 16, 2015

Book Review: Brodeck (2007) by Philippe Claudel and Eat Him if You Like (2009) by Jean Teule

The French know a thing or two about mobs. In fact, they pretty much invented the modern mob back in 1789, and since then they've stayed in game shape with major mob events in 1830 (the July Revolution), 1870 (the Commune), 1968 (the May riots) and, most recently, the 2005 riots in the country's banlieues. It comes as no surprise, then, that a couple of French authors should write novels that dissect the psychology of mob activity.

Brodeck is set in an alternate reality Europe that mostly resembles Austria or Germany in the 1930s. The title character lives in a small village high in the mountains where he works as a low-level government functionary. As the novel begins, Brodeck is summoned to the town's inn where he learns that almost all the men in the village have murdered a man know only as the Outsider. The men ask Brodeck to write a report on what happened in the town that led to the killing of the Outsider. The narrative now skips back and forth between Brodeck's investigation and flashbacks to his grim and tortured life before arriving in the village.

Claudel's novel is a slightly surreal, fable-like meditation on all the ways people can find to despise and persecute those unlike themselves. The Outsider who ends up being killed is emphatically more symbol (a saint? a holy fool? God?) than a character. He's odd and eccentric, mostly silent, and it feels like he's dropped into the village after an adventure in one of Italo Calvino's fabulist novels. The slightly whimsical nature of the Outsider is offset by Brodeck's back story, which is a litany of some of the 20th century's showcase atrocities--concentrations camps, pogroms, persecution, and total war. Claudel's novel veers towards the didactic from time to time, but he more than makes up for it with some wonderful world-building. His alternative Europe is artfully done, and his detailed descriptions of the village and its citizens are beautifully realized.

Eat Him if You Want is the nasty, brutish and short take on mob behavior. It's actually an almost blow for blow recounting of a true event in French history that took place in 1870. The setting is a small village during a summer fair. Word has come from the north that the war with Prussia, only a few weeks old, is going badly for France, which is simply more bad news on top of the drought which is gripping the region. A local haute bourgeoisie man, Alain de Moneys, comes to the fair to conduct some business and a few members of a semi-drunken crowd think (wrongly) that they hear him say something pro-Prussian. What starts as anger among a few drunks metastasizes into an orgy of violence directed against Moneys. For over two hours he's beaten and tortured in ways only French peasants could dream up, culminating in his being burnt alive and, yes, partially eaten. His death was the definition of senseless, and many of his attackers were later arrested and executed or sent to penal colonies.

No gruesome detail is spared in Teule's novella, but the blood and horror is leavened with black humor and a tone of ironic detachment that makes the savagery and madness on display all the more affecting. Teule doesn't ask us to draw lessons from this historical incident, or even try to understand more than the simplest of motivations behind the attack. He simply shows in clinical detail how a mass of people can turn into not just killers, but brutal architects of pain.The worst thing about the crime is that it reveals how imaginatively cruel the average person can be and how willing they are to put their sickening fantasies into action.

Both novels are in the Premier League of harrowing, and not to be read on a crowded subway train where people are likely to be testy and react badly if you bump into them while your nose is buried in one of these books. And kudos to Gallic Books for bringing out Eat Him if You Like and a raft of other French novels in translation which I'm slowly working my through. Allons-y!

Brodeck is set in an alternate reality Europe that mostly resembles Austria or Germany in the 1930s. The title character lives in a small village high in the mountains where he works as a low-level government functionary. As the novel begins, Brodeck is summoned to the town's inn where he learns that almost all the men in the village have murdered a man know only as the Outsider. The men ask Brodeck to write a report on what happened in the town that led to the killing of the Outsider. The narrative now skips back and forth between Brodeck's investigation and flashbacks to his grim and tortured life before arriving in the village.

Claudel's novel is a slightly surreal, fable-like meditation on all the ways people can find to despise and persecute those unlike themselves. The Outsider who ends up being killed is emphatically more symbol (a saint? a holy fool? God?) than a character. He's odd and eccentric, mostly silent, and it feels like he's dropped into the village after an adventure in one of Italo Calvino's fabulist novels. The slightly whimsical nature of the Outsider is offset by Brodeck's back story, which is a litany of some of the 20th century's showcase atrocities--concentrations camps, pogroms, persecution, and total war. Claudel's novel veers towards the didactic from time to time, but he more than makes up for it with some wonderful world-building. His alternative Europe is artfully done, and his detailed descriptions of the village and its citizens are beautifully realized.

Eat Him if You Want is the nasty, brutish and short take on mob behavior. It's actually an almost blow for blow recounting of a true event in French history that took place in 1870. The setting is a small village during a summer fair. Word has come from the north that the war with Prussia, only a few weeks old, is going badly for France, which is simply more bad news on top of the drought which is gripping the region. A local haute bourgeoisie man, Alain de Moneys, comes to the fair to conduct some business and a few members of a semi-drunken crowd think (wrongly) that they hear him say something pro-Prussian. What starts as anger among a few drunks metastasizes into an orgy of violence directed against Moneys. For over two hours he's beaten and tortured in ways only French peasants could dream up, culminating in his being burnt alive and, yes, partially eaten. His death was the definition of senseless, and many of his attackers were later arrested and executed or sent to penal colonies.

No gruesome detail is spared in Teule's novella, but the blood and horror is leavened with black humor and a tone of ironic detachment that makes the savagery and madness on display all the more affecting. Teule doesn't ask us to draw lessons from this historical incident, or even try to understand more than the simplest of motivations behind the attack. He simply shows in clinical detail how a mass of people can turn into not just killers, but brutal architects of pain.The worst thing about the crime is that it reveals how imaginatively cruel the average person can be and how willing they are to put their sickening fantasies into action.

Both novels are in the Premier League of harrowing, and not to be read on a crowded subway train where people are likely to be testy and react badly if you bump into them while your nose is buried in one of these books. And kudos to Gallic Books for bringing out Eat Him if You Like and a raft of other French novels in translation which I'm slowly working my through. Allons-y!

Tuesday, October 6, 2015

Film Review: Black Mass (2015)

If Black Mass was a pizza it would only have one topping; if it was a car it would be a base model Toyota Corolla; and if it was a day of the week it would be Wednesday. Black Mass is the blandest gangster film that's ever been made. It's not dull, it's not bad, but it leaves absolutely no impression on your cinematic palate. The film tells the true story of Whitey Bulger, a small-time Boston gangster who became a big-time gangster in the 1980s thanks to the tacit support of the FBI, who were relying on Bulger to give them intel on Boston's sole mafia family. Bulger gave them very little real info, but the protection and tips he got from the FBI (and one agent in particular) let him rule Boston's underworld for more than a decade.

Where Black Mass goes wrong is in concentrating on the FBI's involvement with Bulger. It's true that this is what makes the Bulger case of news interest, but it has very little cinematic value. The appeal of gangster films lies in the gangster lifestyle. Goodfellas is a masterpiece because it shows the visceral appeal of life in the mob, especially how that life was for street-level hoods. The Godfather also shows us a gangster lifestyle, albeit one that's built around an operatic plot and an acidic attack on the myth of the American Dream. Black Mass goes through the motions of showing Bulger whacking some people, beating up others, and generally being feral and threatening, but we don't get any clear idea of what his criminal empire was built on. His downfall began with his involvement with jai alai games in Florida. The film does a terrible job of telling us what jai alai is and how Bulger profits from it. And Bulger's underlings are barely developed. We register their presence, but they might as well be nameless extras for all the impact they have. Instead of describing the gangster life, the film gives us scene after scene of guys sitting around tables in homes and offices doing nothing but talk, talk, talk. At the halfway point in the film I began to feel I was watching some kind of dramatic re-enactment show on the History Channel.

The actors all turn in capable performances, but they're held back by a script that lacks wit and energy. All the salient points in Bulger's career are covered, which is fine for an essay, but not so charming in a film. And one odd thing I noticed is that either the actors or the scriptwriter have no ear for swearing. Everyone curses up a storm, but it always sounds awkward and forced. Goodfellas evidently holds the record for sweariest film of all time but in that film the expletives felt natural and almost poetic. In Black Mass the curses are there to enliven otherwise dreary dialogue sequences.

Where Black Mass goes wrong is in concentrating on the FBI's involvement with Bulger. It's true that this is what makes the Bulger case of news interest, but it has very little cinematic value. The appeal of gangster films lies in the gangster lifestyle. Goodfellas is a masterpiece because it shows the visceral appeal of life in the mob, especially how that life was for street-level hoods. The Godfather also shows us a gangster lifestyle, albeit one that's built around an operatic plot and an acidic attack on the myth of the American Dream. Black Mass goes through the motions of showing Bulger whacking some people, beating up others, and generally being feral and threatening, but we don't get any clear idea of what his criminal empire was built on. His downfall began with his involvement with jai alai games in Florida. The film does a terrible job of telling us what jai alai is and how Bulger profits from it. And Bulger's underlings are barely developed. We register their presence, but they might as well be nameless extras for all the impact they have. Instead of describing the gangster life, the film gives us scene after scene of guys sitting around tables in homes and offices doing nothing but talk, talk, talk. At the halfway point in the film I began to feel I was watching some kind of dramatic re-enactment show on the History Channel.

The actors all turn in capable performances, but they're held back by a script that lacks wit and energy. All the salient points in Bulger's career are covered, which is fine for an essay, but not so charming in a film. And one odd thing I noticed is that either the actors or the scriptwriter have no ear for swearing. Everyone curses up a storm, but it always sounds awkward and forced. Goodfellas evidently holds the record for sweariest film of all time but in that film the expletives felt natural and almost poetic. In Black Mass the curses are there to enliven otherwise dreary dialogue sequences.

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

Film Review: Figures in a Landscape (1970)

One of the great things about filmmaking in the late 1960s and early '70s is that no one knew what they were doing. The studio system in Hollywood was collapsing into bankruptcy, formerly reliable film genres such as musicals and westerns were dying on the vine, and laxer censorship meant whole new avenues of creative expression were opened up. All this meant that producers, who were as much in the dark as anyone, were willing to take a chance on projects that were non-traditional; in fact, some producers were probably hunting for oddball films to make in the hope that they'd catch the next wave that would carry them out of the film production wilderness. And that's probably how Figures in a Landscape got made.

Figures is not a good film, but it's eccentric ambitions make it very watchable. The two stars are Robert Shaw and Malcolm McDowell, the director was Joseph Losey, and Shaw also wrote the screenplay, which is based on a novel by Barry England. The minimalist story has two men, Mac and Ansell, on the run from the authorities in an unnamed country. We don't know their crime, their guilt or innocence, or the political character of the country they're in. They're pursued by an ominous black helicopter that seems able to find them at will and direct ground forces against them. The landscape of the title is arid and mountainous (it was shot in Spain), and might be a country in southern Europe or even Latin America. The men's goal is a snowy mountain range that marks the border with another country.

Harold Pinter's name isn't on the credits, but it might as well be. Shaw and Losey had both worked with Pinter on multiple occasions and his influence is very clear. This is an action film that's also a bickering, claustrophobic, absurdist drama, with the helicopter and its faceless pilot becoming a symbol of...well, whatever you want, I guess. Mac and Ansell dislike each other from the beginning and are reluctant allies. They spend most of their time quarreling or telling redundant stories about their lives back in Britain, and like many Pinter characters they attach enormous importance to the most trivial details of their lives. As a Pinter play, it's not a very good one. The dialogue isn't sharp or witty or off-kilter enough, and Mac (Shaw) gets far too much of the dialogue. Ansell (McDowell) spends most of the film looking scared and not much else.