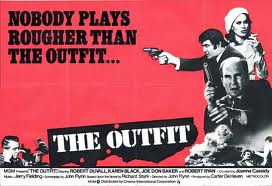

I've written previously about the Parker novels by Richard Stark on this blog (you can read the post here), and this early 1970s adaptation of the novel by the same name comes closest to capturing the flavour of Stark's writing. Point Blank is the best film made from a Parker novel, but it's not really true to the spirit of the books. And although The Outfit feels more like its source material, it still manages to miss the boat. It's entertaining, but there's some wonkiness that's hard to overlook.

The first oddity is that short, balding Robert Duvall is cast in the Parker role. Now Duvall can play tough, but he just doesn't appear tough (why does he hold his gun in that odd way?), and Parker is certainly described as looking rangy and menacing. The second oddity is that his character is called Earl Macklin instead of Parker. I can't even guess why that change was made. Joe Don Baker plays Macklin's sidekick and he would have been a much better choice for the Parker character.

The story is one that Stark would recycle in Butcher's Moon: the Outfit has killed Macklin's brother in retaliation for he and Earl having robbed a bank a few years previously that was controlled by the Outfit. Macklin goes to the Outfit's boss and demands a payment of 250k as a penalty for killing his brother (such brotherly love). The Outfit refuses, and Macklin and his sidekick begin knocking over Outfit properties until they agree to pay the "fine." They try to double-cross Macklin and that turns out to be a bad idea.

And now a word about the Outfit. The Outfit is a feature of the old Parker novels, and it's one that now feels somewhat dated. To a certain degree it plays the role that SPECTRE did in the James Bond novels. Both are highly organized criminal enterprises with interests in all kinds of criminal activity. The Outfit is essentially the Mafia, only it seems to be run entirely run by WASPy types. In Parker's world, every city has a parallel criminal economy, and it's all run by the Outfit.

The scenes of Macklin knocking over Outfit properties are done very well, and a lot of Stark's terse, muscular dialogue makes it to the screen to great effect. The acting is equally fine, which isn't surprising given that cast is stuffed with veteran character actors, everyone from Elisha Cook to Robert Ryan. Some parts are more uneven. Bruce Surtees is the cinematographer (he shot a lot Clint Eastwood's films) and he gives some scenes a nicely gritty look, but a lot of other scenes just look like a made-for-TV movie. Macklin's relationship with his girlfriend, played by Karen Black, is pointless and has an unpleasantly abusive aspect. The ending is the biggest disappointment. It feels hastily assembled and finishes on a jokey note that is very un-Parker.

The Outfit is worth watching, but I wouldn't go out of my way to track it down.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Film Review: Seduced and Abandoned (1964)

This film is remarkably similar in theme to the novel Bell' Antonio, which I reviewed in August. Both are about the corrosive effects of Sicilian codes of honour and machismo. The novel takes a look at an arranged marriage that falls apart, while Seduced, made in 1964, is about various frustrated attempts to arrange a marriage.

Seduced begins during a siesta in the affluent Ascalone household. Everyone's asleep except Peppino Califano, who's engaged to Matilde Ascalone, and Agnese, Don Vincenzo Ascalone's youngest (15) and most beautiful daughter. Peppino and Agnese steal away to a deserted corner of the large house and the deed is done. It's not clear if they love or even like each other, but they definitely succumb to a mutual lust, with Peppino leading the charge.

Sure enough, Agnese is left pregnant by her one tryst with Peppino and that begins a comic war between Vincenzo and the Califano family. Vincenzo wants Peppino to marry Agnese to save his family's honour. Peppino counters that he doesn't want to marry a girl who can be seduced so easily; it clearly means she's a whore at heart. The battle takes some twists and turns, and in the end the Califanos find themselves being forced to beg Vincenzo for his daughter. And along the way there's been an attempted honour killing and what can only be called a ritual kidnapping. A wedding finally takes place, but it's left nothing but scorched earth behind it and no future prospects for happiness.

This film is described as a comedy, but only in the sense that it's a ruthless satire of Sicilian culture. There are some laughs, but what's to be enjoyed here is the meticulous examination of the hypocrisy and idiocy of Sicilian concepts of honor and pride. None of the characters come away looking good or innocent, and the final shot in the film is a brutal but effective commentary on the pointlessness of upholding honour. Pietro Germi was the director, and he did an excellent job of keeping a nice balance between acidic satire and silliness.

The cast is excellent, led by Saro Urzi as Vincenzo. You may recognize him from The Godfather where he played the father of the Sicilian girl Michael Corleone takes as his wife. Choosing Urzi for this role was clearly a tip of the hat to Seduced and Abandoned from Francis Ford Coppola. The cinematography is also good, and the soundtrack by Carlo Rustichelli sounds remarkably like something Ennio Morricone might have created. I wonder who influenced who.

Sicilian codes of honour don't have much contemporary resonance, but the film can still be enjoyed for the sheer craft and pleasure and wit that went into making it. There's a film version of Bell' Antonio and I'm going to have to hunt it down to compare and contrast.

Seduced begins during a siesta in the affluent Ascalone household. Everyone's asleep except Peppino Califano, who's engaged to Matilde Ascalone, and Agnese, Don Vincenzo Ascalone's youngest (15) and most beautiful daughter. Peppino and Agnese steal away to a deserted corner of the large house and the deed is done. It's not clear if they love or even like each other, but they definitely succumb to a mutual lust, with Peppino leading the charge.

Sure enough, Agnese is left pregnant by her one tryst with Peppino and that begins a comic war between Vincenzo and the Califano family. Vincenzo wants Peppino to marry Agnese to save his family's honour. Peppino counters that he doesn't want to marry a girl who can be seduced so easily; it clearly means she's a whore at heart. The battle takes some twists and turns, and in the end the Califanos find themselves being forced to beg Vincenzo for his daughter. And along the way there's been an attempted honour killing and what can only be called a ritual kidnapping. A wedding finally takes place, but it's left nothing but scorched earth behind it and no future prospects for happiness.

This film is described as a comedy, but only in the sense that it's a ruthless satire of Sicilian culture. There are some laughs, but what's to be enjoyed here is the meticulous examination of the hypocrisy and idiocy of Sicilian concepts of honor and pride. None of the characters come away looking good or innocent, and the final shot in the film is a brutal but effective commentary on the pointlessness of upholding honour. Pietro Germi was the director, and he did an excellent job of keeping a nice balance between acidic satire and silliness.

The cast is excellent, led by Saro Urzi as Vincenzo. You may recognize him from The Godfather where he played the father of the Sicilian girl Michael Corleone takes as his wife. Choosing Urzi for this role was clearly a tip of the hat to Seduced and Abandoned from Francis Ford Coppola. The cinematography is also good, and the soundtrack by Carlo Rustichelli sounds remarkably like something Ennio Morricone might have created. I wonder who influenced who.

Sicilian codes of honour don't have much contemporary resonance, but the film can still be enjoyed for the sheer craft and pleasure and wit that went into making it. There's a film version of Bell' Antonio and I'm going to have to hunt it down to compare and contrast.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Book Review: Family Planning (2008) by Karan Mahajan

If there's one common thread running through the Indian literature I've read it's the frustration felt by the Indian middle and upper classes with the chaotic, corrupt state of their country. Balancing this is a love for India's eccentricities, traditions and downright absurdities. Add in the siren call of the West and you can see that Indian writers have some rather big issues to deal with.

Family Planning takes the madness of modern Indian life and compresses it into the Ahuja family of New Delhi. The family, all fifteen of them, are led by Rakesh Ahuja, a cabinet minister in the government. His cabinet portfolio has him in charge of "flyovers", an elevated series of expressways that are intended to lift traffic above the sprawl and congestion of Delhi. His oldest son, Arjun, 16, is a big fan of Bryan Adams and wants to start his own rock band in order to impress a schoolgirl he sees on the bus everyday.

That's the basic setup for the novel, but beyond that the author doesn't do a lot with his two main characters. Rakesh's political career comes a cropper for entirely farcical reasons, and Arjun's band gets nowhere entirely because they have absolutely no talent. Mahajan is mostly interested in showing the contradictions in Indian life, such as a cabinet minister trying to tame Delhi's traffic while at the same increasing it with his oversized family. Mahajan is a clever and amusing writer, but his novel borders on being plotless. The writing is entertaining but after a certain point it needs to be attached to a story.

Family Planning takes the madness of modern Indian life and compresses it into the Ahuja family of New Delhi. The family, all fifteen of them, are led by Rakesh Ahuja, a cabinet minister in the government. His cabinet portfolio has him in charge of "flyovers", an elevated series of expressways that are intended to lift traffic above the sprawl and congestion of Delhi. His oldest son, Arjun, 16, is a big fan of Bryan Adams and wants to start his own rock band in order to impress a schoolgirl he sees on the bus everyday.

That's the basic setup for the novel, but beyond that the author doesn't do a lot with his two main characters. Rakesh's political career comes a cropper for entirely farcical reasons, and Arjun's band gets nowhere entirely because they have absolutely no talent. Mahajan is mostly interested in showing the contradictions in Indian life, such as a cabinet minister trying to tame Delhi's traffic while at the same increasing it with his oversized family. Mahajan is a clever and amusing writer, but his novel borders on being plotless. The writing is entertaining but after a certain point it needs to be attached to a story.

Monday, November 21, 2011

Film Review: Season of the Witch (2011)

You could do a lot worse than watching this on DVD. Season of the Witch came out for a short and disastrous theatrical run in January of this year, and was harpooned by every critic in the solar system. It's actually pretty good if you accept it as a B-movie that wants to deliver some swordplay and supernatural CGI.

I checked out some of the reviews by nationally known critics (Roger Ebert, PeterTravers) and found it interesting that the same critics who thought Witch was an abomination managed to give Captain America: The First Avenger glowing reviews. I watched Captain earlier this week and found it so lame I didn't even bother to review it. But I will now.

Captain America is barely a movie. At about the halfway point of the film Steve Rogers (Captain America) finds himself in Italy in WW II and hears that his best friend is being held captive by the Germans. He goes to rescue him. He succeeds. The rest of the film is almost entirely an extended montage of Steve kicking Nazi ass. There's no plot, there's no character development, and the action scenes are lifeless. The acting never rises above competent, and none of the characters has any personality.

Witch, on the other hand, has a solid, coherent plot that has Nicholas Cage and Ron Perlman as ex-Crusaders delivering a witch for trial to a monastery. Basically, it's a variation on a quest story. It's the kind of tried and true plot that's worked well in everything from westerns to samurai films. They face various dangers en route and then a nasty surprise awaits them at the monastery. The locations used in Hungary and Austria are atmospheric, and the director gives the action elements a lot of energy. And Cage and Perlman are always watchable.

So why the animosity directed towards it? I think the reason is that it's a straightforward B-movie and not an ironic B-movie like Planet Terror or Hobo With a Shotgun. An unaplogetic B-movie doesn't allow much room for critical comment; you either find it entertaining or you don't. But why did Captain America, which by any standard is a poor movie, get such a polite response? I'd hazard a guess that a lot of critics are closet comic book nerds who somehow feel it's their duty to cheer each new additon to the superhero genre.

Let me be clear about Witch, it's no classic. Some of the actors are forgettable, the CGI isn't the best, and the dialogue isn't going to win any scriptwriting awards. But despite all that the film is a lot of fun. It wants to be imaginative, scary, fast-moving and violent, but without Michael Bay levels of bombast and overkill. and on those terms it succeeds.

I checked out some of the reviews by nationally known critics (Roger Ebert, PeterTravers) and found it interesting that the same critics who thought Witch was an abomination managed to give Captain America: The First Avenger glowing reviews. I watched Captain earlier this week and found it so lame I didn't even bother to review it. But I will now.

Captain America is barely a movie. At about the halfway point of the film Steve Rogers (Captain America) finds himself in Italy in WW II and hears that his best friend is being held captive by the Germans. He goes to rescue him. He succeeds. The rest of the film is almost entirely an extended montage of Steve kicking Nazi ass. There's no plot, there's no character development, and the action scenes are lifeless. The acting never rises above competent, and none of the characters has any personality.

Witch, on the other hand, has a solid, coherent plot that has Nicholas Cage and Ron Perlman as ex-Crusaders delivering a witch for trial to a monastery. Basically, it's a variation on a quest story. It's the kind of tried and true plot that's worked well in everything from westerns to samurai films. They face various dangers en route and then a nasty surprise awaits them at the monastery. The locations used in Hungary and Austria are atmospheric, and the director gives the action elements a lot of energy. And Cage and Perlman are always watchable.

So why the animosity directed towards it? I think the reason is that it's a straightforward B-movie and not an ironic B-movie like Planet Terror or Hobo With a Shotgun. An unaplogetic B-movie doesn't allow much room for critical comment; you either find it entertaining or you don't. But why did Captain America, which by any standard is a poor movie, get such a polite response? I'd hazard a guess that a lot of critics are closet comic book nerds who somehow feel it's their duty to cheer each new additon to the superhero genre.

Let me be clear about Witch, it's no classic. Some of the actors are forgettable, the CGI isn't the best, and the dialogue isn't going to win any scriptwriting awards. But despite all that the film is a lot of fun. It wants to be imaginative, scary, fast-moving and violent, but without Michael Bay levels of bombast and overkill. and on those terms it succeeds.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Film Review: The Princess of Montpensier (2010)

Do people still want to see historical epics like this? I thought this film might offer a bit of a wrinkle on an old and tired genre, but it doesn't. The costumes are gorgeous and detailed, there's romantic and political intrigue, and there's a fair amount of swordplay. The problem is that it all feels tired and paint-by-numbers.

The actors are all good, with Melanie Thierry being quite beautiful in the role of the beautiful Princess Montpensier. In fact, she looks a bit too good. This is the 16th century, after all, but Thierry always looks like she's just finished shooting a shampoo commerical. I never got past the feeling that I was watching actors playing dress-up.

The story is about the arranged marriage of Marie to the Prince de Montpensier. This being a period piece, Marie, naturally enough, doesn't love the Prince, but pines for Henri de Guise, played by Gaspard Ulliel, who looks like he's just back from doing an aftershave commercial. Passions run high, love follows a rocky course, and the Catholic/Protestant wars rage in the background.

Maybe Bertrand Tavernier, the director, felt he needed a costume drama on his resume, but I can't see any other reason to make this film; the plot is generic and even the action elements are lacking in energy. If you want to a fairly recent French costume epic that really delivers the goods watch The Horseman On the Roof with Juliette Binoche.

The actors are all good, with Melanie Thierry being quite beautiful in the role of the beautiful Princess Montpensier. In fact, she looks a bit too good. This is the 16th century, after all, but Thierry always looks like she's just finished shooting a shampoo commerical. I never got past the feeling that I was watching actors playing dress-up.

The story is about the arranged marriage of Marie to the Prince de Montpensier. This being a period piece, Marie, naturally enough, doesn't love the Prince, but pines for Henri de Guise, played by Gaspard Ulliel, who looks like he's just back from doing an aftershave commercial. Passions run high, love follows a rocky course, and the Catholic/Protestant wars rage in the background.

Maybe Bertrand Tavernier, the director, felt he needed a costume drama on his resume, but I can't see any other reason to make this film; the plot is generic and even the action elements are lacking in energy. If you want to a fairly recent French costume epic that really delivers the goods watch The Horseman On the Roof with Juliette Binoche.

Monday, November 14, 2011

Film Review: The Mill and the Cross (2011)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted The Procession to Calvary in 1564. It was commissioned by Nicholaes Jonghelinck, a rich merchant from Antwerp. The purpose of the painting, according to this film, was to depict Christ's suffering and crucifixion within the context of the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands.

The above synopsis isn't appreciably leaner than the information supplied in The Mill and the Cross. The film attempts to literally take us inside a painting, to deconstruct and almost atomize its various visual and symbolic elements. Lech Wajeski, the director, shows us how Bruegel took the raw material of daily life and shaped it into a political allegory, and Wajeski does this without turning his film into some kind of dry docudrama.

As befits a story about a painting, The Mill and the Cross is all about images, and Wajeski does a stunning job of making his own images stand comparison to Bruegel's. There's really not a lot more that can said about the film; you either respond to the idea of the film and its images or you don't. It definitely worked for me. The trailer below gives a clear idea of what to expect.

The above synopsis isn't appreciably leaner than the information supplied in The Mill and the Cross. The film attempts to literally take us inside a painting, to deconstruct and almost atomize its various visual and symbolic elements. Lech Wajeski, the director, shows us how Bruegel took the raw material of daily life and shaped it into a political allegory, and Wajeski does this without turning his film into some kind of dry docudrama.

As befits a story about a painting, The Mill and the Cross is all about images, and Wajeski does a stunning job of making his own images stand comparison to Bruegel's. There's really not a lot more that can said about the film; you either respond to the idea of the film and its images or you don't. It definitely worked for me. The trailer below gives a clear idea of what to expect.

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Book Review: Falling Glass (2011) by Adrian McKinty

If you've read McKinty's Michael Forsythe trilogy (Dead I May Well Be, The Dead Yard, The Bloomsday Dead) your enjoyment of Falling Glass may be slightly impaired. The reason is that the shadow of Michael Forsythe looms large over this thriller. Forsythe is a compelling character: crafty, funny, tough, ruthless, and a great observer of the world around him. He's always the most interesting (and dangerous) person in the room. Forsythe makes a few appearances in Falling Glass and that means Killian, the lead character, suffers by comparison. Killian is an adequate hero, but he just feels like a slightly paler version of Forsythe. Much is made of the fact that Killian is an Irish Traveller, but his ethnicity doesn't translate into a character who's significantly different from Forsythe.

As a thriller, Falling Glass is in the Premier League. This is largely because McKinty does not try and put his plots together like a Swiss watch. A great many thrillers have a flowchart feel to them: plot point follows plot point in reliable progression, and even the surprises have a predictable feel to them. In McKinty's plots, as in the real world, shit happens. That means plans and schemes suddenly go pear-shaped and cause stories to spin off in unexpected directions. In Dead I May Well Be what begins as a crime thriller suddenly becomes an escape from prison thriller. The prison section of that novel is a classic of its kind.

This novel has Killian, a semi-retired tough guy, being tasked with finding the ex-wife of a Northern Irish aviation tycoon named Coulter. The woman, Rachel, is a barely recovering drug addict and has two young daughters. She also has a laptop that contains very damaging information about Coulter. It's because of the laptop that Coulter, unbeknownst to Killian, has sent Markov, a Russian hitman, after Killian. Once Killian finds Rachel, Markov's job is to kill her and recover the laptop. Killian discovers what Markov's purpose is and he decides to protect Rachel and her girls. Cue the tension, the violence, and a very unexpected conclusion. The plotting here isn't quite up to the standard of the Forsythe novels, but it's still very good. The main drawback is that things don't get underway quickly enough thanks to sidetrips to Mexico and Macau that aren't really necessary.

Falling Glass, like the trilogy, isn't all about the running, the hiding, the shooting, and the killing. McKinty is a literary writer. He writes dialogue that's so lively it practically dances, and his characters certainly have far more depth than is usual in a thriller. In this novel he even brings some layers to Markov. Implacable, taciturn Russian hitmen are a dime a dozen in pop culture, but Markov is allowed to be more than just a walking, talking gun.

The most interesting aspect to this novel is that Killian, Rachel, and Markov seem to be trapped in their roles by forces beyond their control. Killian was out of the crime game until the collapse of the Irish economy; Rachel is a prisoner of drug addiction; and Markov is the warped product of the fall of the U.S.S.R and the brutality of the Russian military. Even Coulter is suffering through a meltdown in the airline business. In short, the drama we see is a by-product of collapsing societies and economies. In contrast to this are the Travellers, who give shelter to Killian and Rachel. Their traditional, communal, tribal, nomadic existence seems idyllic and healthy in comparison to the harsh realities of the straight world.

The conclusion to Falling Glass is really going to annoy some people. I thought it was the highlight of the novel. It's The Italian Job cliffhanger with a subtle twist. The twist is that the two participants are, I'm guessing, stand-ins for the twin poles of Irish history: the lyrical and the profanely violent. In literary terms Ireland has been punching above its weight for a very long time, but, by the same token, it's also known an amazing amount of violence and tragedy for an island that would fit quite easily into southern Ontario.

Falling Glass would be up there with the Forsythe novels but for the character of Killian, and some imagery and metaphors that feel forced and awkward. But that's nitpicking. This is still one of the best thrillers I've read this year.

As a thriller, Falling Glass is in the Premier League. This is largely because McKinty does not try and put his plots together like a Swiss watch. A great many thrillers have a flowchart feel to them: plot point follows plot point in reliable progression, and even the surprises have a predictable feel to them. In McKinty's plots, as in the real world, shit happens. That means plans and schemes suddenly go pear-shaped and cause stories to spin off in unexpected directions. In Dead I May Well Be what begins as a crime thriller suddenly becomes an escape from prison thriller. The prison section of that novel is a classic of its kind.

This novel has Killian, a semi-retired tough guy, being tasked with finding the ex-wife of a Northern Irish aviation tycoon named Coulter. The woman, Rachel, is a barely recovering drug addict and has two young daughters. She also has a laptop that contains very damaging information about Coulter. It's because of the laptop that Coulter, unbeknownst to Killian, has sent Markov, a Russian hitman, after Killian. Once Killian finds Rachel, Markov's job is to kill her and recover the laptop. Killian discovers what Markov's purpose is and he decides to protect Rachel and her girls. Cue the tension, the violence, and a very unexpected conclusion. The plotting here isn't quite up to the standard of the Forsythe novels, but it's still very good. The main drawback is that things don't get underway quickly enough thanks to sidetrips to Mexico and Macau that aren't really necessary.

Falling Glass, like the trilogy, isn't all about the running, the hiding, the shooting, and the killing. McKinty is a literary writer. He writes dialogue that's so lively it practically dances, and his characters certainly have far more depth than is usual in a thriller. In this novel he even brings some layers to Markov. Implacable, taciturn Russian hitmen are a dime a dozen in pop culture, but Markov is allowed to be more than just a walking, talking gun.

The most interesting aspect to this novel is that Killian, Rachel, and Markov seem to be trapped in their roles by forces beyond their control. Killian was out of the crime game until the collapse of the Irish economy; Rachel is a prisoner of drug addiction; and Markov is the warped product of the fall of the U.S.S.R and the brutality of the Russian military. Even Coulter is suffering through a meltdown in the airline business. In short, the drama we see is a by-product of collapsing societies and economies. In contrast to this are the Travellers, who give shelter to Killian and Rachel. Their traditional, communal, tribal, nomadic existence seems idyllic and healthy in comparison to the harsh realities of the straight world.

The conclusion to Falling Glass is really going to annoy some people. I thought it was the highlight of the novel. It's The Italian Job cliffhanger with a subtle twist. The twist is that the two participants are, I'm guessing, stand-ins for the twin poles of Irish history: the lyrical and the profanely violent. In literary terms Ireland has been punching above its weight for a very long time, but, by the same token, it's also known an amazing amount of violence and tragedy for an island that would fit quite easily into southern Ontario.

Falling Glass would be up there with the Forsythe novels but for the character of Killian, and some imagery and metaphors that feel forced and awkward. But that's nitpicking. This is still one of the best thrillers I've read this year.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Shakespeare Review: Richard II

No one tell the Tea Party, but Shakespeare may well have been on their side. In Richard II the king is opposed and deposed because he's been a profligate spender and tax happy. A tax and spend liberal, as it were. The political and dynastic machinations of England's peers provide the backbone of this play, but its power lies in the character of Richard, and Shakespeare's meditations on the duality of man and king.

In a way, Richard is a cousin to Hamlet, the man whose tragedy. according to Laurence Olivier, was that he could not make up his mind. Richard can't decide whether to act like a king or a man, and his vacillations make him a pitiable and tragic figure. In the early stages of the play Richard is all kingly pride and condescension as he banishes Bolingbroke (later Henry IV) for having taken part in a treasonous plot. When Bolingbroke's father, the Duke of Lancaster, dies Bolingbroke returns to England to claim his dukedom and lead a rebellion against Richard. When Richard returns from Ireland and hears of the rebellion he says, with regal disdain:

For every man that Bolingbroke hath pressed

To lift the shrewd steel against our golden crown,

God for his Richard hath in heavenly pay

A glorious angel, then, if angels fight,

Weak men must fall, for Heaven still guards the

right.

Richard's showing a lot of confidence before the big match. But mere moments later Richard gets the bad news that most of the peerage has turned against him and he now faces very long odds. It's at this point that Richard's character splits in two. Half of him becomes a frightened, friendless man who suddenly sees his own mortality as something inevitable and separate from his role as a king. With shocking clarity Richard realizes that kings are very much flesh and blood creatures, and he reveals this to his few followers in a witty and heartbreaking speech shown in the clip below. The performance is a bit too jocular, but it captures the spirit of the thing.

For the rest of play Richards swings between the role of king and common man. In times of stress he cracks and bemoans his fate, welcoming the idea of simply abdicating. At other times his pride takes hold and he sees himself as a king, having a divinely-ordained obligation to fight against whatever odds to oppose those who would overthrow a man chosen by God to rule on Earth. He dies as a king, sword in hand, cut down by assassins.

Although Shakespeare always paid lip service to the concept of the divine right of kings, and showed equal support for an ordered, hierarchical society, in Richard II we see that there was more than a little ambivalence in his mind on the subject of kings. I think Shakespeare felt this way due to a profound feeling of existential dread, probably rooted in atheism. In Shakespeare's time atheism was, according to historian Keith Thomas, a not uncommon belief, and where atheism goes, agnosticism follows in even greater numbers. In showing Richard losing faith in his kingship, Shakespeare was possibly showing his own loss of faith. It's notable that in this play and others, characters who speak of death in the abstract speak of God and Heaven; characters who are facing their own imminent demise, as Richard is in the clip above, speak of death as the bleak, meaningless end of existence.

As though to replace the idea of kings with something that transcends flesh and blood, Shakespeare invents the concept of nationalism in Richard II. Well, invent may be going a bit far, but prior to Shakespeare if nationalism existed it was bound up with the role of a monarch as a divine representative. Shakespeare has Bolingbroke's father delivers a rousing speech that pretty clearly states that it is England's greatness that produces great kings, not great kings that make England great. The speech is in the clip below from 1:30 to 4:08

Shakespeare adds to his nationalist theme with a short speech by the soon-to-be exiled Mowbray, who feels the bitterest part of leaving England's shores is that he will no longer be able to speak English. Mowbray doesn't mention the loss of family and friends, it's the loss of his language, which he almost seems to regard as part of his soul, that causes him the most grief. A lesser writer would have Mowbray bemoaning leaving behind family, wealth and England's worldly charms. Shakespeare shows England having a spiritual hold on Mowbray.

I give Richard II a solid 8 out of 10 on the Bard-o-Meter.

In a way, Richard is a cousin to Hamlet, the man whose tragedy. according to Laurence Olivier, was that he could not make up his mind. Richard can't decide whether to act like a king or a man, and his vacillations make him a pitiable and tragic figure. In the early stages of the play Richard is all kingly pride and condescension as he banishes Bolingbroke (later Henry IV) for having taken part in a treasonous plot. When Bolingbroke's father, the Duke of Lancaster, dies Bolingbroke returns to England to claim his dukedom and lead a rebellion against Richard. When Richard returns from Ireland and hears of the rebellion he says, with regal disdain:

For every man that Bolingbroke hath pressed

To lift the shrewd steel against our golden crown,

God for his Richard hath in heavenly pay

A glorious angel, then, if angels fight,

Weak men must fall, for Heaven still guards the

right.

Richard's showing a lot of confidence before the big match. But mere moments later Richard gets the bad news that most of the peerage has turned against him and he now faces very long odds. It's at this point that Richard's character splits in two. Half of him becomes a frightened, friendless man who suddenly sees his own mortality as something inevitable and separate from his role as a king. With shocking clarity Richard realizes that kings are very much flesh and blood creatures, and he reveals this to his few followers in a witty and heartbreaking speech shown in the clip below. The performance is a bit too jocular, but it captures the spirit of the thing.

For the rest of play Richards swings between the role of king and common man. In times of stress he cracks and bemoans his fate, welcoming the idea of simply abdicating. At other times his pride takes hold and he sees himself as a king, having a divinely-ordained obligation to fight against whatever odds to oppose those who would overthrow a man chosen by God to rule on Earth. He dies as a king, sword in hand, cut down by assassins.

Although Shakespeare always paid lip service to the concept of the divine right of kings, and showed equal support for an ordered, hierarchical society, in Richard II we see that there was more than a little ambivalence in his mind on the subject of kings. I think Shakespeare felt this way due to a profound feeling of existential dread, probably rooted in atheism. In Shakespeare's time atheism was, according to historian Keith Thomas, a not uncommon belief, and where atheism goes, agnosticism follows in even greater numbers. In showing Richard losing faith in his kingship, Shakespeare was possibly showing his own loss of faith. It's notable that in this play and others, characters who speak of death in the abstract speak of God and Heaven; characters who are facing their own imminent demise, as Richard is in the clip above, speak of death as the bleak, meaningless end of existence.

As though to replace the idea of kings with something that transcends flesh and blood, Shakespeare invents the concept of nationalism in Richard II. Well, invent may be going a bit far, but prior to Shakespeare if nationalism existed it was bound up with the role of a monarch as a divine representative. Shakespeare has Bolingbroke's father delivers a rousing speech that pretty clearly states that it is England's greatness that produces great kings, not great kings that make England great. The speech is in the clip below from 1:30 to 4:08

Shakespeare adds to his nationalist theme with a short speech by the soon-to-be exiled Mowbray, who feels the bitterest part of leaving England's shores is that he will no longer be able to speak English. Mowbray doesn't mention the loss of family and friends, it's the loss of his language, which he almost seems to regard as part of his soul, that causes him the most grief. A lesser writer would have Mowbray bemoaning leaving behind family, wealth and England's worldly charms. Shakespeare shows England having a spiritual hold on Mowbray.

I give Richard II a solid 8 out of 10 on the Bard-o-Meter.

Monday, November 7, 2011

Film Review: Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010)

This film began life a few years ago as a short shown on YouTube. The feature version feels like a short that's been stretched waaaay out. The high concept premise is that Santa and his elves are actually malevolent creatures from Finnish folklore who like to kill children. Things begin with a team of engineers digging something big out of a mountain, which turns out to be a giant, horned Santa creature frozen into a block of ice. Meanwhile Santa's elves, apparently alerted to this excavation, start kidnapping local children in preparation for the big guy thawing out and feeling hungry. A young boy named Pietari somehow fathoms all this and attempts to warn his father, but, of course, dad won't listen until things are almost too late.

Half the fun in a horror/fantasy story is the setup, the sense of rising dread or excitement we get as things get creepier, stranger or scarier. Rare Exports does a terrible job of setup. Nothing's explained, the story lurches forward, characters are barely introduced, and the whole folklore aspect of the story is barely described or developed. Really, the director only seems interested in the final 15 minutes of the film wherein we get most of the special effects and some tongue-in-cheek riffs on action movie tropes. If as much imagination and attention to detail had been paid to the rest of the film this would be something to remember.

I'd have more to say about Rare Exports but there's really so little to it. It looks good, the acting is fine, but the storytelling, the nuts and bolts of building up atmosphere, are so clumsily handled that the film ends up feeling like a first draft for a another, better film.

Half the fun in a horror/fantasy story is the setup, the sense of rising dread or excitement we get as things get creepier, stranger or scarier. Rare Exports does a terrible job of setup. Nothing's explained, the story lurches forward, characters are barely introduced, and the whole folklore aspect of the story is barely described or developed. Really, the director only seems interested in the final 15 minutes of the film wherein we get most of the special effects and some tongue-in-cheek riffs on action movie tropes. If as much imagination and attention to detail had been paid to the rest of the film this would be something to remember.

I'd have more to say about Rare Exports but there's really so little to it. It looks good, the acting is fine, but the storytelling, the nuts and bolts of building up atmosphere, are so clumsily handled that the film ends up feeling like a first draft for a another, better film.

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Book Review: Rivers of London (2011) by Ben Aaronovitch

Right now the book world is awash in fantasy literature. This is largely thanks to the twin aftershocks of Harry Potter and the Twilight books. Anything, it seems, with a fantasy or horror element, and any mash-up entangling the two with other genres, gets a warm greeting from the publishing industry. This has produced a lot of dreck, usually involving Buffy clones finding romance as they splatter the undead.

Rivers of London avoids zombies and romance, and is mostly successful, largely thanks to some solid comic writing and a clever mash-up of a police procedural and the world of magic. Our hero is Peter Grant, a young police constable who looks to be headed for a dull, behind-the-scenes job in the Met. All that changes when he's assigned to guard a crime scene involving a headless corpse and then ends up taking a witness statement from a ghost. From there it's a short step to becoming an apprentice wizard under the tutelage of Chief Inspector Thomas Nightingale, who is, yes, a fully-fledged wizard. Nightingale's remit, which is known only to a few of his superiors, is to investigate supernatural crimes and keep the peace on the otherworldly side of London.

The headless corpse is the first in a series of gruesome deaths perpetrated by a vengeful ghost who is using the bodies of Londoners to reenact a bizarre and bloody Punch and Judy show. On top of trying to collar the murderous ghost, Grant and Nightingale have to keep the peace between the gods of London's rivers. London apparently has many rivers, mostly hidden, but each has it's god, and Mother Thames and Father Thames rule over them all.

Aaronovitch has a slick, chirpy writing style that owes a lot to Terry Pratchett, and he's smart enough to have Grant make a couple of references to Harry Potter just so we know that Grant realizes he's dropped into an absurd and improbable world. Aaronovitch also does a good job of explaining, or creating a theory of, how magic works. This is always a bit of a problem in books about magic; the authors either ignore the how and why, or they come up with a dopey, New Age-y explanation. Aaronovitch takes a more technical approach, and it works rather well. Even better is his decision to make the cop elements as real as possible. Take away the magical element and this would be a solid police procedural mystery; Grant talks like a cop, he follows Met protocol, he relies as much on police equipment as he does on magic, and he really seems to enjoy being a policeman.

Where Aaronovitch runs into trouble is with the plot. The final section of the book is a bit of a mess. The first problem is that the author begins to tie himself into thick, confusing knots explaining the magical and supernatural logic behind what's happening. Another bad decision is to have a climactic scene set in a packed Royal Opera House in which the killer ghost reveals himself and a massive riot breaks out. The problem is that this isn't the finale of the book. The riot ends, the reader's excitement evaporates, and the real end comes a short time later. The opera house scene is very Pratchettesque, but Sir Terry would have ended the novel right there.

Notice something? I haven't mentioned the river gods when discussing the killer ghost plot. That's because Aaronovitch fails to make the two plots intertwine in any meaningful way. That would be fine if the river gods' story was a sub-plot, but it isn't. A big chunk of the novel is devoted to dealing with the various gods and, while all of it is interesting and clever, it really doesn't have a damn thing to do with the main plot. The river gods need their own novel, not a superfluous role in a ghostly murder mystery.

There's a sequel to Rivers of London called Moon Over Soho (werewolves, I expect), and yet another is in the pipeline. I'll definitely read the next one and hope that the author has let an editor get a look at it first.

Rivers of London avoids zombies and romance, and is mostly successful, largely thanks to some solid comic writing and a clever mash-up of a police procedural and the world of magic. Our hero is Peter Grant, a young police constable who looks to be headed for a dull, behind-the-scenes job in the Met. All that changes when he's assigned to guard a crime scene involving a headless corpse and then ends up taking a witness statement from a ghost. From there it's a short step to becoming an apprentice wizard under the tutelage of Chief Inspector Thomas Nightingale, who is, yes, a fully-fledged wizard. Nightingale's remit, which is known only to a few of his superiors, is to investigate supernatural crimes and keep the peace on the otherworldly side of London.

The headless corpse is the first in a series of gruesome deaths perpetrated by a vengeful ghost who is using the bodies of Londoners to reenact a bizarre and bloody Punch and Judy show. On top of trying to collar the murderous ghost, Grant and Nightingale have to keep the peace between the gods of London's rivers. London apparently has many rivers, mostly hidden, but each has it's god, and Mother Thames and Father Thames rule over them all.

Aaronovitch has a slick, chirpy writing style that owes a lot to Terry Pratchett, and he's smart enough to have Grant make a couple of references to Harry Potter just so we know that Grant realizes he's dropped into an absurd and improbable world. Aaronovitch also does a good job of explaining, or creating a theory of, how magic works. This is always a bit of a problem in books about magic; the authors either ignore the how and why, or they come up with a dopey, New Age-y explanation. Aaronovitch takes a more technical approach, and it works rather well. Even better is his decision to make the cop elements as real as possible. Take away the magical element and this would be a solid police procedural mystery; Grant talks like a cop, he follows Met protocol, he relies as much on police equipment as he does on magic, and he really seems to enjoy being a policeman.

Where Aaronovitch runs into trouble is with the plot. The final section of the book is a bit of a mess. The first problem is that the author begins to tie himself into thick, confusing knots explaining the magical and supernatural logic behind what's happening. Another bad decision is to have a climactic scene set in a packed Royal Opera House in which the killer ghost reveals himself and a massive riot breaks out. The problem is that this isn't the finale of the book. The riot ends, the reader's excitement evaporates, and the real end comes a short time later. The opera house scene is very Pratchettesque, but Sir Terry would have ended the novel right there.

Notice something? I haven't mentioned the river gods when discussing the killer ghost plot. That's because Aaronovitch fails to make the two plots intertwine in any meaningful way. That would be fine if the river gods' story was a sub-plot, but it isn't. A big chunk of the novel is devoted to dealing with the various gods and, while all of it is interesting and clever, it really doesn't have a damn thing to do with the main plot. The river gods need their own novel, not a superfluous role in a ghostly murder mystery.

There's a sequel to Rivers of London called Moon Over Soho (werewolves, I expect), and yet another is in the pipeline. I'll definitely read the next one and hope that the author has let an editor get a look at it first.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)