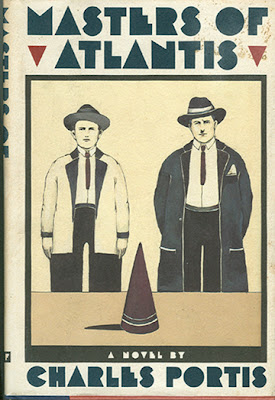

If Masters of Atlantis isn't the Great American Novel, it's surely the Great American Comic Novel. Say the words "great novel" and one instantly thinks of a work of fiction that tackles important moral questions, significant social issues, and moments of historic import; the sort of book one imagines was written by someone with a brow constantly furrowed in thought, living in a room with a single window facing a brick wall, and who only took brief breaks from the Underwood in order to light unfiltered Camels, all the better to furrow his or her brow even more. But does a nation's great novel have to adopt a stern and forbidding mien? By my own definition a great national novel should be one that you could hand to an extraterrestrial and say, "Here's the one book that tells you all about the essential character of the people whose nation you've just landed in/enslaved/vaporized." And by that criteria Masters of Atlantis by Charles Portis (author of True Grit) is, for me, the Great American Novel. And I like to imagine it was written in the summer on a porch shaded by wisteria vines, the author stopping occasionally for a snack of iced tea and red velvet cake.

From the outside looking in, America's personality dial is permanently set to 11 with citizens who are charming, maddening, innocent, foolish, xenophobic, gullible, optimistic, crafty, adventurous, bigoted, energetic, and ignorant, not forgetting all the go-getters, do-gooders and flim-flam men. This crazy quilt of emotions and characters is brilliantly portrayed in Masters, woven into a story that revolves around what might be the core of the American character: belief. More on this later.

The novel opens at the end of World War One with young Lamar Jimmerson, an American soldier, being sold the Codex Pappus, a bundle of papers that's supposed to represent the collected wisdom of the lost city of Atlantis. And from that beginning, Jimmerson, who has an unshakable belief in his Atlantean lore, more or less accidentally founds a cult called Gnomonism with himself at its head. His title is the "Master." The cult's popularity waxes and wanes, reaching its zenith in the 1930s, and ending in that most American of dwellings, a double-wide trailer home. The plot, like so many of the characters in the book, is almost rudderless, but this is far from being a fault, it's simply reflecting the rootless, peripatetic side of American life.

Along the way Jimmerson is aided and hindered by a cavalcade of American archetypes and eccentrics. The most notable of the bunch is Austin Popper and his sidekick Squanto, a talking blue jay. Popper is the distillate that would result from boiling down Elmer Gantry, Bob Hope and Foghorn Leghorn. Jimmerson is a kindly fool whose affability and credulity blinds him to the charlatans and nitwits who are pulled into Gnomonism's weak gravitational field. The female characters, it should be noted, are the only ones who seem to be possessed with an ounce of common sense.

Portis' comic style is best described as deadpan; he tells tall tales in the plainest possible way, and that matter-of-factness, his attention to the niggling details of eccentricity, produces some sublime humor. Portis' comedy is never shouty or jokey; it's like a low frequency vibration that turns solids into liquids, or in this case, turns some of the more self-important aspects of the American character into comic gold. And like the very best comic writers (P.G. Wodehouse springs to mind) you can flip to almost any page of the book and find something delightful:

"Through a friend at the big Chicago marketing firm of Targeted Sales, Inc., he got his hands on a mailing list titled Odd Birds of Illinois and Indiana, which, by no means exhaustive, contained the names of some seven hundred men who ordered strange merchandise through the mail, went to court often, wrote letters to the editor, wore unusual headgear, kept rooms that were filled with rocks or old newspapers. In short, independent thinkers who might be more receptive to the Atlantean lore than the general run of men."

And..

"You think you can treat me this way because I'm poor and have to go to night law school."

"All law schools should be conducted at night."

And...

"He boiled some eggs, a long business at this altitude, and made coffee with the same water. He ate two eggs and left two for Cezar. On one he idly scrawled, Help. Captive. Gypsy caravan."

If there's one grand, unifying theme to the novel it's Portis' identification of the fact that Americans are the most enthusiastic believers on the planet. Their nation was founded, in part, by people looking to follow religious beliefs that Europeans viewed as dangerous or eccentric, and ever since then the US has lead the world in the production of cults and crazes, everything from Mormonism to Scientology to birthers. It's a nation that sometimes seems to be filled with people who think that with just the right formula or mantra or revelation or algorithm, the final, absolute, one-size-fits-all Truth will be revealed to the chosen. And no other country could produce so many social clubs like the Shriners, Moose Lodge, Optimists, and Rotarians, just to name a few. It would seem that if you took three random Americans and locked them in a room, after an hour they would emerge with a new religion, conspiracy theory or service club. Possibly all three. But what Americans believe in most of all is America; it's a cult and a religion, and if you don't believe me just take note of how omnipresent the American flag is in the American landscape. The US is awash in representations of Old Glory, and in that regard it's unique among democracies. Flag worship is the litmus test for any totalitarian state, but in the US of A the common citizens have turned the Stars and Stripes into a red, white and blue Shroud of Turin.

I've read Masters several times, and what motivated me to do this review is The Master, Paul Thomas Anderson's latest film. It's a pretty poor effort (my review) about the leader of a Scientology-like cult. It's really the photographic negative, unfunny version of Masters of Atlantis, but it made me wish someone, preferably the Coen brothers, would take a crack at filming Portis' novel. But until that happens, and you want to experience a fictional look at America's obsession with cults, stick to Portis.

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Thursday, April 18, 2013

Film Review: Drum (1976)

Django Unchained, which I reviewed back in January, is a bad film. Drum, which I caught on Netflix last night, is also a bad film. Both films are about slavery in the Old South but in some significant ways Django stands out as much the worse film. Drum has no pretensions to being anything other than a middling budget exploitation picture. The story revolves around slavery, but what's on sale here are copious amounts of violence and female nudity. The title character, played by boxer Ken Norton with a woodenness that sends splinters shooting off the screen, is a slave raised in a New Orleans whorehouse. His mother Mariana, who is white, owns the bordello, but has never told Drum that he's her son. Drum thinks his mother is Mariana's faithful maid. Drum catches the attention of DeMarigny, a Frenchman who's, well, let's just say he's a triple-coated villain, a man so low he stole his French accent from Pepe Le Pew. DeMarigny wants to use Drum as a fighter against other slaves, but Drum is a reluctant scrapper. After a variety of brawls and murders, Drum must flee New Orleans. Mariana sells him to Hammond, a slave owner who has a plantation on which he does nothing but breed slaves. More nudity and violence ensues, climaxing with a slave rebellion that leaves almost everyone, white and black, dead. Roll credits.

As mentioned, Drum is an exploitation picture and on that basis it earns a blue ribbon. There's nary a scene that doesn't feature sex, violence or nudity. What's rather amazing is that the script manages to pull in all the exploitation elements without interrupting the narrative flow. Everything about Drum is lurid and over-the-top, but the script is a solid, logical piece of writing. The scriptwriter also earns points for the dialogue, which is pulpy to the max and not afraid to sound ridiculous. Some credit also has to go to the cast. Pros like Warren Oates, John Colicos, Yaphet Kotto and Royal Dano tackle their lurid characters with gusto and almost manage to compensate for "actors" like Ken Norton. Lastly, the film deserves credit for an ending that adheres to reality (the blacks are wiped out) and also allows for some ambiguity. Hammond (Warren Oates) is in most respects a thorough villain, but a brief scene earlier in the film involving the beating of a slave shows us that a part of him (a very small part) is conflicted about treating humans as chattel. In the last scene in the film Hammond chooses to let Drum escape rather than gun him down as he would have every reason to do as white slave owner. It's a surprising ending for what's otherwise a pretty conventional film.

The strengths, relatively speaking, of Drum do a good job of highlighting even further the deficiencies of Django Unchaned. Tarantino's script is a mess: uneven in tone, overlong, and stuffed with gratuitous scenes and dialogue. Drum's script isn't going to win any awards, but it's model of efficient storytelling, and when the word "nigger" is used it's done in a natural, honest way. When Tarantino writes "nigger" in his scripts I always get the feeling he does it to prove how naughty he is. An odd thing about Tarantino is that as much as he's a devotee of genre/exploitation pictures, he's also a prude. Quentin is happy to show people being riddled with bullets or saying "nigger" with every breath, but nudity? sex? God forbid! Miscegenation was the primal fear and fantasy of Southern society, but it doesn't exist for Tarantino. The ending of Django stands in stark contrast to that of Drum. In Tarantino's wish-fulfillment fantasy world (see Inglourious Basterds for further evidence) the black hero rides off into the sunset with his white enemies all slain, his girl by his side, and a horse that can dance. Drum runs off into the night with nothing but a look of terror on his face. No prizes for guessing which film is more historically accurate.

I'm not going to say that Drum is a good film, but for the demographic it was intended for it succeeds brilliantly. And if it reminds you in any way of Django Unchained that's because Tarantino seems to havestolen been heavily influenced by elements of Drum. And for optimum viewing pleasure both films should be seen at a drive-in accompanied by your favourite legal/illegal stimulant.

As mentioned, Drum is an exploitation picture and on that basis it earns a blue ribbon. There's nary a scene that doesn't feature sex, violence or nudity. What's rather amazing is that the script manages to pull in all the exploitation elements without interrupting the narrative flow. Everything about Drum is lurid and over-the-top, but the script is a solid, logical piece of writing. The scriptwriter also earns points for the dialogue, which is pulpy to the max and not afraid to sound ridiculous. Some credit also has to go to the cast. Pros like Warren Oates, John Colicos, Yaphet Kotto and Royal Dano tackle their lurid characters with gusto and almost manage to compensate for "actors" like Ken Norton. Lastly, the film deserves credit for an ending that adheres to reality (the blacks are wiped out) and also allows for some ambiguity. Hammond (Warren Oates) is in most respects a thorough villain, but a brief scene earlier in the film involving the beating of a slave shows us that a part of him (a very small part) is conflicted about treating humans as chattel. In the last scene in the film Hammond chooses to let Drum escape rather than gun him down as he would have every reason to do as white slave owner. It's a surprising ending for what's otherwise a pretty conventional film.

The strengths, relatively speaking, of Drum do a good job of highlighting even further the deficiencies of Django Unchaned. Tarantino's script is a mess: uneven in tone, overlong, and stuffed with gratuitous scenes and dialogue. Drum's script isn't going to win any awards, but it's model of efficient storytelling, and when the word "nigger" is used it's done in a natural, honest way. When Tarantino writes "nigger" in his scripts I always get the feeling he does it to prove how naughty he is. An odd thing about Tarantino is that as much as he's a devotee of genre/exploitation pictures, he's also a prude. Quentin is happy to show people being riddled with bullets or saying "nigger" with every breath, but nudity? sex? God forbid! Miscegenation was the primal fear and fantasy of Southern society, but it doesn't exist for Tarantino. The ending of Django stands in stark contrast to that of Drum. In Tarantino's wish-fulfillment fantasy world (see Inglourious Basterds for further evidence) the black hero rides off into the sunset with his white enemies all slain, his girl by his side, and a horse that can dance. Drum runs off into the night with nothing but a look of terror on his face. No prizes for guessing which film is more historically accurate.

I'm not going to say that Drum is a good film, but for the demographic it was intended for it succeeds brilliantly. And if it reminds you in any way of Django Unchained that's because Tarantino seems to have

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

Book Review: Pride and Prejudice (1813) by Jane Austen

|

| Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Elizabeth Bennet. |

First off, I don't think I've ever read a novel that manages to be equally superb in terms of plotting, prose and characterization. Pride and Prejudice has many moving parts, changes of direction, and plots and counter-plots. Purely on the basis of storytelling this is an amazing achievement, but to then add in so many beautifully realized, iconic characters described in witty, playful prose is nothing short of miraculous. I can think of a variety of novelists who've mastered two out of three of these qualities, but all three? It's a very short list.

The other thing that struck me was that Pride and Prejudice has some of the characteristics of espionage fiction. Let me explain. A great deal of the story revolves around what could be called intelligence work or spycraft. Elizabeth Bennet is constantly trying to ascertain the motives, actions and goals of, well, just about everyone, including people in her own family. And to accomplish this she debriefs and interrogates people, analyzes intelligence reports (letters), tries to see through disinformation campaigns, and works to uncover double agents like Caroline Bingley. Elizabeth's role as a Regency Geroge Smiley gives the novel the same narrative drive as a spy thriller. It's as though Darcy is a Great Power and a variety of individuals are working feverishly to make him an ally or turn him into an enemy of another individual. Here's a couple of passages that give a taste of Elizabeth's role as a spymaster:

"After wandering along the lane for two hours, giving way to every variety of thought; re-considering events, determining probabilities..."

"...and my dear aunt, if you do not tell me in an honourable manner, I shall certainly be reduced to tricks and strategems to find out."

And indeed she does strategize and determine probabilities, so much so at times that part of the pleasure of the novel is watching, as it were, the wheels turning in Elizabeth's head as she plans her next move or tries the to see through the "fog of war" and gauge what the opposition is up to. Now if only the novel had ended with this postscript: Elizabeth Bennet Will Return In...

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Film Review: Fraulein Doktor (1969)

In the 1960s and '70s there were two kinds of B-movies in Europe. The most common kind were just like B-movies elsewhere: low-budget, unambitious, and full of cheap thrills. The other kind were films made as co-productions in Yugoslavia. The benefits of shooting in Yugoslavia were that local crews were cheaper, the country's varied terrain could double as Africa or even Norway, and, most importantly, the Yugoslavian Army was very obliging in allowing its men and equipment to be used in big battle scenes. And that's why films like Kelly's Heroes, Taras Bulba, The Long Ships and Genghis Khan ended up there; if your budget was limited but you wanted some spectacle in your film, Yugoslavia was the only choice.

Fraulein Doktor is one of the better made-in-Yugoslavia films from that era. The lead actors are all British, the key behind-the-camera people are Italian, and the hundreds of extras are, of course, the Yugoslavian Army. These Tower of Babel film productions usually exhibit all sorts of glitches, usually involving badly-dubbed local actors and production values (excluding battle scenes) that are a bit thrift shop. Fraulein Doktor is surprisingly well-made from start to finish. Set during WW I, the title character is a German Mata Hari-type spy played by the ravishing Suzy Kendall. The plot is more episodic than it should be, with the film starting with Doktor sneaking into England to arrange the assassination of Lord Kitchener. One of her fellow spies is caught and is turned by British intelligence. There follows a lengthy flashback in which we see Doktor steal a French poison gas formula by seducing the female scientist who invented it. Doktor then moves on to a scheme to steal the plans for the allied defensive positions on the eve of General Ludendorff's big offensive late in the war. Hot on her trail is Kenneth More as the head of British Intelligence and James Booth as the traitorous German spy. The ever-suave Nigel Green plays More's opposite number in German Intelligence.

What makes this film a cut above others from that era is a first-rate cast, a plot that handles the espionage elements with originality and intelligence, and, most importantly, an amazing final sequence that shows a gas attack on the French and British trenches. It's a truly hellish and original sequence, with German troops and their cavalry horses covered in protective suits to guard against a new gas (the one stolen by Doktor) that kills on contact with the skin. Fraulein Doktor didn't do very well at the time, which is probably due to a combination of a very downbeat ending and a heroine who is a German patriot. I don't think it's available as a DVD, but Netflix is currently showing it.

Fraulein Doktor is one of the better made-in-Yugoslavia films from that era. The lead actors are all British, the key behind-the-camera people are Italian, and the hundreds of extras are, of course, the Yugoslavian Army. These Tower of Babel film productions usually exhibit all sorts of glitches, usually involving badly-dubbed local actors and production values (excluding battle scenes) that are a bit thrift shop. Fraulein Doktor is surprisingly well-made from start to finish. Set during WW I, the title character is a German Mata Hari-type spy played by the ravishing Suzy Kendall. The plot is more episodic than it should be, with the film starting with Doktor sneaking into England to arrange the assassination of Lord Kitchener. One of her fellow spies is caught and is turned by British intelligence. There follows a lengthy flashback in which we see Doktor steal a French poison gas formula by seducing the female scientist who invented it. Doktor then moves on to a scheme to steal the plans for the allied defensive positions on the eve of General Ludendorff's big offensive late in the war. Hot on her trail is Kenneth More as the head of British Intelligence and James Booth as the traitorous German spy. The ever-suave Nigel Green plays More's opposite number in German Intelligence.

What makes this film a cut above others from that era is a first-rate cast, a plot that handles the espionage elements with originality and intelligence, and, most importantly, an amazing final sequence that shows a gas attack on the French and British trenches. It's a truly hellish and original sequence, with German troops and their cavalry horses covered in protective suits to guard against a new gas (the one stolen by Doktor) that kills on contact with the skin. Fraulein Doktor didn't do very well at the time, which is probably due to a combination of a very downbeat ending and a heroine who is a German patriot. I don't think it's available as a DVD, but Netflix is currently showing it.

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

Coming Soon To A Country Near You: Cruel Britannia

In one of Paul Theroux's travel books (sorry, I can't remember which) he said that some countries seem perpetually stuck in their own unique time lines: Turkey, for example, always seems twenty years behind the times; the U.S. is always in the here and now; and Britain and Japan are perpetually one week ahead of everyone else. There wasn't anything scientific in Theroux's analysis, just the feeling that in the case of Britain and Japan, the next big things in culture and technology always seem to be coming from those two countries. There's a kernel of truth in this, which is distressing news for the rest of the world if you've paid attention to British politics in the last couple of years.

In Britain, class warfare is the new black, and fashion-conscious right-wing governments and political parties around the world will be taking notice and adjusting their wardrobes accordingly. Britain's coaliton government, led by the Conservatives under David Cameron, has been aggressively pursuing a fiscal austerity agenda, and their most recent budget put the boots to the millions in the U.K. receiving various kinds of social welfare payments, everything from disability benefits to housing allowances, not to mention opening the NHS to privatization. In sum, the working poor, the unemployed and the disabled are being forced to pay for the follies of Britain's banking sector, a tax system that seems to have been designed by and for Russian oligarchs, and a military that still thinks it's guarding an empire. So Cameron's government has been passing out a lot of economic poison pills to what used to be called the working class (when there was work), but what, one wonders, have they done to put a positive spin on this program of impoverishment? Simple: justify it by tacitly claiming that the people being harmed are scum anyway, so what's the problem? They deserve it.

This past week in England a verdict of guilty was brought down against the Philpotts, a loathsome couple who burned down their own house in a bizarre scheme to emerge as heroes after they rescued their six children. All the children died in the fire. The front page of the Daily Mail is the end product of a campaign by right-wing media outlets and politicians to portray people receiving any kind of social assistance as "scroungers", "parasites" and "feral". These people don't "have" children, they, according to the Daily Mail, "breed." Taking his cue from the tabloids, George Osborne, Britain's Chancellor of the Exchequer, wasted no time in inferring that the Philpotts' crimes were somehow a result of social welfare spending. What we have here is no less than class warfare, albeit a war that is completely one-sided. Britain's right-wing papers are to the Conservatives what Fox News is to the Republicans in the U.S., and on behalf of the Conservatives they have been waging a propaganda war against the working class, furiously stoking resentment and fear amongst the middle class, and turning the working poor against those living on the "dole."

Papers like the Sun, Daily Mail and the Telegraph accomplish this by acting as a media form of Predator drone, keeping a lidless eye focused on Britain's have-nots. Should any member of the underclasses engage in some kind of benefits fraud or enjoy a glitzy "lifestyle" thanks to social welfare payments, the papers authorize a launch of hyper-intensive press coverage that mocks and demonizes both the individual and the welfare state that has supposedly created this monstrous person. The gaudy Philpott case has encouraged the right-wing press and their Conservative pilot fish to come out into the open with their cynical strategy of scapegoating and punishing the underclass in order to enrich the classes above.

This kind of open class warfare hasn't yet made the jump to North America. In the U.S., politicians like to pretend there's no class system, and any attempt to vilify the mostly African-American underclasses runs the risk of being viewed as undiluted racism. What happens instead is that Fox News and the like spend most of their time attacking/smearing those advocating or defending what are perceived as left-wing causes. Here in Canada, the federal Conservative government is waging a relentless propaganda campaign (paid for by the taxpayer) that extolls the benefits of Conservative rule. In their eyes, the underclass is anyone who opposes oil sands development. This is not to say that playing the class warfare card won't happen in either country. Rightists throughout the world increasingly sing from the same hymn book, so if a winning right-wing formula emerges in one part of the world, it's sure to be copied in another.

The interesting question is why the class warfare card is being played now in Britain. The simple answer is that this is the natural next step in the capitalist counter-revolution that began with the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979. In the decades after WW II most Western governments enacted wide-ranging social welfare policies and looked upon unions with favour, or at least tolerance. The main reason for this, especially in Europe, was fear of communism. Thatcher put an end to all that. Capitalism, flying under the banners of Thatcherism and Reaganomics, was determined to roll back the economic order to a state that pre-dated WW I. Using terms like globalization, rationalization, healthy competition, and meritocracy, rightists presented this counter-revolution as an exercise in scientific, logical management of the world economy. That myth dissolved in the international financial crisis of 2007-08. What to do next? In Britain, it seems the answer is to take the PR filters off and have at the underclasses with all the vitriol the tabloid press can muster. And who can blame them? The upper classes have been searching for a new blood sport ever since the ban on fox hunting in 2002. Tally ho, and see you on the barricades!

In Britain, class warfare is the new black, and fashion-conscious right-wing governments and political parties around the world will be taking notice and adjusting their wardrobes accordingly. Britain's coaliton government, led by the Conservatives under David Cameron, has been aggressively pursuing a fiscal austerity agenda, and their most recent budget put the boots to the millions in the U.K. receiving various kinds of social welfare payments, everything from disability benefits to housing allowances, not to mention opening the NHS to privatization. In sum, the working poor, the unemployed and the disabled are being forced to pay for the follies of Britain's banking sector, a tax system that seems to have been designed by and for Russian oligarchs, and a military that still thinks it's guarding an empire. So Cameron's government has been passing out a lot of economic poison pills to what used to be called the working class (when there was work), but what, one wonders, have they done to put a positive spin on this program of impoverishment? Simple: justify it by tacitly claiming that the people being harmed are scum anyway, so what's the problem? They deserve it.

This past week in England a verdict of guilty was brought down against the Philpotts, a loathsome couple who burned down their own house in a bizarre scheme to emerge as heroes after they rescued their six children. All the children died in the fire. The front page of the Daily Mail is the end product of a campaign by right-wing media outlets and politicians to portray people receiving any kind of social assistance as "scroungers", "parasites" and "feral". These people don't "have" children, they, according to the Daily Mail, "breed." Taking his cue from the tabloids, George Osborne, Britain's Chancellor of the Exchequer, wasted no time in inferring that the Philpotts' crimes were somehow a result of social welfare spending. What we have here is no less than class warfare, albeit a war that is completely one-sided. Britain's right-wing papers are to the Conservatives what Fox News is to the Republicans in the U.S., and on behalf of the Conservatives they have been waging a propaganda war against the working class, furiously stoking resentment and fear amongst the middle class, and turning the working poor against those living on the "dole."

Papers like the Sun, Daily Mail and the Telegraph accomplish this by acting as a media form of Predator drone, keeping a lidless eye focused on Britain's have-nots. Should any member of the underclasses engage in some kind of benefits fraud or enjoy a glitzy "lifestyle" thanks to social welfare payments, the papers authorize a launch of hyper-intensive press coverage that mocks and demonizes both the individual and the welfare state that has supposedly created this monstrous person. The gaudy Philpott case has encouraged the right-wing press and their Conservative pilot fish to come out into the open with their cynical strategy of scapegoating and punishing the underclass in order to enrich the classes above.

This kind of open class warfare hasn't yet made the jump to North America. In the U.S., politicians like to pretend there's no class system, and any attempt to vilify the mostly African-American underclasses runs the risk of being viewed as undiluted racism. What happens instead is that Fox News and the like spend most of their time attacking/smearing those advocating or defending what are perceived as left-wing causes. Here in Canada, the federal Conservative government is waging a relentless propaganda campaign (paid for by the taxpayer) that extolls the benefits of Conservative rule. In their eyes, the underclass is anyone who opposes oil sands development. This is not to say that playing the class warfare card won't happen in either country. Rightists throughout the world increasingly sing from the same hymn book, so if a winning right-wing formula emerges in one part of the world, it's sure to be copied in another.

The interesting question is why the class warfare card is being played now in Britain. The simple answer is that this is the natural next step in the capitalist counter-revolution that began with the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979. In the decades after WW II most Western governments enacted wide-ranging social welfare policies and looked upon unions with favour, or at least tolerance. The main reason for this, especially in Europe, was fear of communism. Thatcher put an end to all that. Capitalism, flying under the banners of Thatcherism and Reaganomics, was determined to roll back the economic order to a state that pre-dated WW I. Using terms like globalization, rationalization, healthy competition, and meritocracy, rightists presented this counter-revolution as an exercise in scientific, logical management of the world economy. That myth dissolved in the international financial crisis of 2007-08. What to do next? In Britain, it seems the answer is to take the PR filters off and have at the underclasses with all the vitriol the tabloid press can muster. And who can blame them? The upper classes have been searching for a new blood sport ever since the ban on fox hunting in 2002. Tally ho, and see you on the barricades!

Friday, April 5, 2013

Film Review: The Uninvited Guest (2004)

Tightrope artists are fundamentally ridiculous. One can admire their bravery and physical abilities, but their very particular skill set is pretty much divorced from any real world needs; I mean, if one really needed to traverse a chasm via a thin rope your last choice would be to walk across it. And why do they try to dignify their profession by calling themselves "artists?" That's like lion tamers calling themselves apex predator behavior modification consultants. Writer/directors of thrillers are the tightrope artists of the film world. They're required to throw their protagonists into unlikely and bizarre predicaments, and then devise equally unlikely ways for them to get out of trouble. Look at The Fugitive, for example. Richard Kimble's wife is murdered by a one-armed man and somehow Kimble ends up accused of the crime. To begin with, what idiot would hire a one-armed assassin outside of a kung fu film? And then Kimble makes his escape from prison thanks to a spectacular train wreck and a leap from a dam that a seasoned base jumper would blanch at. And all this in the first twenty minutes! Alfred Hitchcock, the master of the unlikely thriller, camouflaged the eccentricities of his plots with humor, visual style and glamorous casting. He seemed to realize and appreciate that the more unlikely the story, the more he was allowed to indulge in his auteur side. The plot of, say, North by Northwest, almost becomes secondary to all the cinematic razzle-dazzle on view.

Guillem Morales is the writer and director of The Uninvited Guest, and he's also a hell of a tightrope artist. His protagonist is Felix, a youngish architect living in a large, rambling house somewhere in Spain. Felix's long-term girlfriend has just left him and is now in an apartment of her own, although some of her stuff is still in the house. One night a stranger comes to Felix's door and asks if he can use the phone. Felix allows him in and leaves the room while the man makes his call. He comes back a few minutes later and finds that the man has gone, but he hasn't heard the front door close. From that point on Felix becomes convinced that the man is somehow hiding in his house; he hears noises, things are left out of place, and he's generally completely spooked. The audience is left with many questions: is Felix going mad? Is he the victim of a plot? Is it a ghost? Is his ex-girlfriend involved? As Felix becomes more paranoid the story takes some twists and turns that are, well, completely bonkers.

For the most part, Morales stays on the tightrope. At a few points he slips and is left dangling by his fingers, even his teeth, but he manages to get to the other side without falling into the canyon of "Oh, for Chrissake, this is effing ridiculous! Let's watch House Hunters." A big part of the film's entertainment value comes from watching Morales devise ever more byzantine plot twists, but, like many thrillers with outrageous concepts, the finish doesn't quite equal what's come before. That said, The Uninvited Guest is a worthwhile film based solely on its audacity and the director's enthusiasm for making his character jump through some pretty strange hoops. Not a first-class thriller, but certainly a strong performer in the minor leagues of the genre.

Guillem Morales is the writer and director of The Uninvited Guest, and he's also a hell of a tightrope artist. His protagonist is Felix, a youngish architect living in a large, rambling house somewhere in Spain. Felix's long-term girlfriend has just left him and is now in an apartment of her own, although some of her stuff is still in the house. One night a stranger comes to Felix's door and asks if he can use the phone. Felix allows him in and leaves the room while the man makes his call. He comes back a few minutes later and finds that the man has gone, but he hasn't heard the front door close. From that point on Felix becomes convinced that the man is somehow hiding in his house; he hears noises, things are left out of place, and he's generally completely spooked. The audience is left with many questions: is Felix going mad? Is he the victim of a plot? Is it a ghost? Is his ex-girlfriend involved? As Felix becomes more paranoid the story takes some twists and turns that are, well, completely bonkers.

For the most part, Morales stays on the tightrope. At a few points he slips and is left dangling by his fingers, even his teeth, but he manages to get to the other side without falling into the canyon of "Oh, for Chrissake, this is effing ridiculous! Let's watch House Hunters." A big part of the film's entertainment value comes from watching Morales devise ever more byzantine plot twists, but, like many thrillers with outrageous concepts, the finish doesn't quite equal what's come before. That said, The Uninvited Guest is a worthwhile film based solely on its audacity and the director's enthusiasm for making his character jump through some pretty strange hoops. Not a first-class thriller, but certainly a strong performer in the minor leagues of the genre.

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Book Review: Angelmaker (2012) by Nick Harkaway

First off, with a name like Nick Harkaway the least you can do with your life is write a rollicking, violent, madly entertaining genre mashup of steampunk and SF about a madman's plot to destroy the world. But Harkaway should really be the fair-faced, clean-limbed commander of a frigate, or a polar explorer, or a smasher of plots to steal Britain's secrets and treasures. Instead of any of those more interesting life choices, Harkaway has given us Angelmaker. So be it. I hope he's happy with his decision.

There is simply too much going on in Angelmaker to provide a synopsis of reasonable length, so I'll stick to the highlights. The main character is Joe Spork, a thirtyish mender of clocks and automata, and son of the late and infamous Matthew Spork, a crook's crook in the London underworld. Joe receives a commission to repair a peculiar clockwork device and is thereby thrown headlong into a plot to destroy the world through the agency of the Apprehension Engine, a device that alters human consciousness so that it can always perceive the truth, thus causing, in theory, all kinds of strife. The evil genius behind this plan is Shem Shem Tsien, an ageless Asian dictator who's a charmless combination of Pol Pot and Vlad the Impaler. Tsien is aided by the Ruskinites, a priestly cult that worships John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic. Joe's allies are Edie Bannister, a retired spy who was the Modesty Blaise of WW II; a diverse group of ex-gangsters; and Polly Cradle, the woman who turns out to be the love of his life.

Like the best fantasy/steampunk writers, Harkaway doesn't let anything stand in the way of his imagination, which goes off like an oversized Catherine wheel. Angelmaker is an excellent adventure story based solely on its imaginative energy and diversity, but Harkaway brings more to the party. Unlike most entries in this field, there's an anger and ferocity and, yes, political consciousness that sets it apart. The political sub-text to the novel isn't overplayed or blatant, but it's clear that the author, like his characters, is disgusted with the Machiavellian machinations of the Great Powers and Vested Interests that result in the existence and use of weapons of mass destruction. Looked at from this point of view, Tsien isn't just a stock villain but the distillation of the anti-human nature of realpolitik and the lust for total power.

This novel must also set some kind of record for Britishness. From its homage to P.G. Wodehouse opening (so good I'm nominating Harkaway for membership in the Drones Club) to it's Lancaster bomber finale, this novel is a feast of British cultural references; even the plot feels like it could have been one of the great Dr Who stories. Which is not to say it's some kind of Rule Britannia wet dream. Harkaway certainly doesn't present the British security services in a pleasant light, and at one or two points this begins to feel like an acidic State of Britain novel.

Harkaway's prose is another plus, shifting stylishly and effortlessly from tough to witty to psychologically acute. But this is also where Harkaway stumbles. The only real flaw in Angelmaker is that Harkaway's prose can also be maddeningly discursive, parenthetical and orotund. This type of writing is best enjoyed in small doses, but too often Harkaway can't put a brake on his rococo digressions. One example: late in the novel, as the tension and narrative momentum is building, we hit a speed bump in the form of a pointlessly lengthy description of a character's girth and sex life. This aside would almost be tolerable at the beginning of the story, but coming where it does it feels like the author is just faffing about. To put it in bald terms, Angelmaker would be significantly better if it was about ten per cent shorter. The other ninety per cent of the book is pure gold.

There is simply too much going on in Angelmaker to provide a synopsis of reasonable length, so I'll stick to the highlights. The main character is Joe Spork, a thirtyish mender of clocks and automata, and son of the late and infamous Matthew Spork, a crook's crook in the London underworld. Joe receives a commission to repair a peculiar clockwork device and is thereby thrown headlong into a plot to destroy the world through the agency of the Apprehension Engine, a device that alters human consciousness so that it can always perceive the truth, thus causing, in theory, all kinds of strife. The evil genius behind this plan is Shem Shem Tsien, an ageless Asian dictator who's a charmless combination of Pol Pot and Vlad the Impaler. Tsien is aided by the Ruskinites, a priestly cult that worships John Ruskin, the Victorian art critic. Joe's allies are Edie Bannister, a retired spy who was the Modesty Blaise of WW II; a diverse group of ex-gangsters; and Polly Cradle, the woman who turns out to be the love of his life.

Like the best fantasy/steampunk writers, Harkaway doesn't let anything stand in the way of his imagination, which goes off like an oversized Catherine wheel. Angelmaker is an excellent adventure story based solely on its imaginative energy and diversity, but Harkaway brings more to the party. Unlike most entries in this field, there's an anger and ferocity and, yes, political consciousness that sets it apart. The political sub-text to the novel isn't overplayed or blatant, but it's clear that the author, like his characters, is disgusted with the Machiavellian machinations of the Great Powers and Vested Interests that result in the existence and use of weapons of mass destruction. Looked at from this point of view, Tsien isn't just a stock villain but the distillation of the anti-human nature of realpolitik and the lust for total power.

This novel must also set some kind of record for Britishness. From its homage to P.G. Wodehouse opening (so good I'm nominating Harkaway for membership in the Drones Club) to it's Lancaster bomber finale, this novel is a feast of British cultural references; even the plot feels like it could have been one of the great Dr Who stories. Which is not to say it's some kind of Rule Britannia wet dream. Harkaway certainly doesn't present the British security services in a pleasant light, and at one or two points this begins to feel like an acidic State of Britain novel.

Harkaway's prose is another plus, shifting stylishly and effortlessly from tough to witty to psychologically acute. But this is also where Harkaway stumbles. The only real flaw in Angelmaker is that Harkaway's prose can also be maddeningly discursive, parenthetical and orotund. This type of writing is best enjoyed in small doses, but too often Harkaway can't put a brake on his rococo digressions. One example: late in the novel, as the tension and narrative momentum is building, we hit a speed bump in the form of a pointlessly lengthy description of a character's girth and sex life. This aside would almost be tolerable at the beginning of the story, but coming where it does it feels like the author is just faffing about. To put it in bald terms, Angelmaker would be significantly better if it was about ten per cent shorter. The other ninety per cent of the book is pure gold.

Film Review: The Master (2012)

Like the cult leader at the centre of this film, The Master has presence, style and bombast, but it's also resolutely shallow, long-winded and illogical. Joaquin Phoenix plays Freddie Quell, an alcoholic and all-around dim bulb who comes into the orbit of the "Master". The Master (Philip Seymour Hoffman) is Lancaster Dodd, founder of a cult that bears a passing resemblance to Scientology. In what amounts to a nearly plotless story, Freddie, who would have difficulty holding down a job as a ditch digger, becomes Lancaster's pet project. He keeps Freddie around despite his failings and works to indoctrinate him in his nonsensical ideas about past lives.

The fact that the film looks great and features top-notch acting can't paper over the fact that it doesn't muster a coherent point of view or purpose. The film's main focus is on the relationship between Freddie and Lancaster, and just on that basis the film is a total bust. Freddie is such a witless, loutish fuckup it makes no sense for Lancaster to keep him around. Freddie is the kind of person who makes other people feel intensely uncomfortable and/or creeped out, and Lancaster's inner circle certainly don't seem to like him, so why is Lancaster taken with him? There's no hint of a sexual attraction so we're left with the realization that their illogical relationship is simply the result of bad screenwriting.

The Master also suffers from a surfeit of what could be called arthouse film aesthetic. In practical terms this means scenes are extended past their natural expiration date; meaningful pauses abound; eye-catching shots and artful production design takes precedence over narrative; sequences that should be cut aren't; dialogue is prolix and redundant; and character motivation is always opaque. Writer/diretor Paul Thomas Anderson takes the blame for all this, and unfortunately his stock has been trending downward ever since the superlative Boogie Nights. All his films since then have featured superb acting performances, but his craft as a storyteller has become clumsy and murky. This is hands down Anderson's worst film, and the generally favorable, even fawning, reviews it's received reflect the enthusiasm critics have for Anderson's visual craft and way with actors rather than for his ability to make a film that's as smart as it is sharp-looking. The Master is certainly the best-looking film I've seen in quite a while, but it's also, like Freddie, the most empty-headed.

The fact that the film looks great and features top-notch acting can't paper over the fact that it doesn't muster a coherent point of view or purpose. The film's main focus is on the relationship between Freddie and Lancaster, and just on that basis the film is a total bust. Freddie is such a witless, loutish fuckup it makes no sense for Lancaster to keep him around. Freddie is the kind of person who makes other people feel intensely uncomfortable and/or creeped out, and Lancaster's inner circle certainly don't seem to like him, so why is Lancaster taken with him? There's no hint of a sexual attraction so we're left with the realization that their illogical relationship is simply the result of bad screenwriting.

The Master also suffers from a surfeit of what could be called arthouse film aesthetic. In practical terms this means scenes are extended past their natural expiration date; meaningful pauses abound; eye-catching shots and artful production design takes precedence over narrative; sequences that should be cut aren't; dialogue is prolix and redundant; and character motivation is always opaque. Writer/diretor Paul Thomas Anderson takes the blame for all this, and unfortunately his stock has been trending downward ever since the superlative Boogie Nights. All his films since then have featured superb acting performances, but his craft as a storyteller has become clumsy and murky. This is hands down Anderson's worst film, and the generally favorable, even fawning, reviews it's received reflect the enthusiasm critics have for Anderson's visual craft and way with actors rather than for his ability to make a film that's as smart as it is sharp-looking. The Master is certainly the best-looking film I've seen in quite a while, but it's also, like Freddie, the most empty-headed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)