Reading this novel is a bit like watching a seriously drunk man wander down a street: for some stretches he manages to hold a steady, sensible course, but then he'll suddenly list over, or attack a turn at an odd angle, or even smack into a pole. Hone's novel, like the drunk, is unpredictable and frequently entertaining in an, "Oh my God, look what he's doing now!" sort of way. In very general terms this is an adventure story, featuring Peter Marlow, the hero of several of Hone's previous novels. The other Marlow stories were built around espionage, and are some of the best spy novels written in the last century. This time out, Marlow is retired and living in the Cotswolds with his wife of one year, Laura, and her autistic eleven-year-old daughter, Clare, from a previous marriage. Peter is working as a schoolteacher at a boarding school. One night an armed and masked intruder bursts into Peter's home and opens fire, missing Peter but killing Laura. Peter assumes British Intelligence has gotten wind of the memoirs he's writing and wants to silence him. Peter now has to go on the run since there are no witnesses to the attack and the police believe he killed Laura. He flees cross-country and takes shelter in the heavily wooded grounds of a huge country estate. The estate is owned by Alice, a wealthy American woman in her late thirties who stumbles upon Peter's hiding place and decides that she believes his story. Alice shelters Peter, and the two of them hatch a plan to snatch back Clare, who is in the hands of the authorities.

I don't want to go on forever describing the twists and turns of the plot, but suffice it to say that things get progressively more bonkers, and that's exactly the dilemma faced by anyone reading this book: is it brilliant or bonkers? Hone's prose and psychological insights are as sharp as ever, but the story goes off in some absolutely mad directions involving fossil hunting, H. Rider Haggard-style adventures in Africa, a cameo appearance by some Hell's Angels, and a section in which Marlow lives an entirely arboreal existence. On one level this novel is an entertaining, if mad, adventure yarn of the kind Geoffrey Household used to write. But Hone isn't that simple a writer. On another level this novel appears to be either an elegy for an England that has lost its empire and unique spirit, or it could equally well be an acidic look at the lies and cruelties that kept the Union Jack flying.

The most notable characteristic of this novel is that it's bathed, no, drenched in Englishness. There are veiled and direct allusions to Arthurian legend, the country house is a warehouse of Victorian bric-a-brac and colonial souvenirs, cricket features prominently in the plot, and the Cotswolds countryside, lovingly described by Hone, is the most English of landscapes; it's home turf for Rupert the Bear and Ratty, Mole and Mr. Toad, and I wouldn't have been that surprised if Marlow had bumped into one of them at some point. The nearly suffocating level of British cultural references reaches a kind of crescendo when Marlow, avoiding a police search of the mansion, escapes down a dumb waiter and is actually "consumed" by a building that contains the quintessence of all that is British:

But everything had been perfectly built and carpentered here and I slipped down gently, soundlessly, through the guts of the house, down this dark gullet, without any problems.

At an early stage in the novel Marlow makes this observation:

There weren't any more dashing people left in England, I suddenly decided; only crafty ones. The idealists, the witty drunks, the eccentrics, they were all gone. Decent fools like Spinks, for example, they got the chop every day, while the cunning, the dull and the vulgar prospered. The small men had come to rule.

Yes, it sounds cranky and reactionary, which is what makes the novel ocassionally seem like a curmudgeonly lament for an England that has disappeared. And at several other points Marlow's views are restated in equally bald terms. At times Hone, and Marlow, seem to be willfully living in the past. There's some un-PC language that would have sounded tone deaf if written twenty years previously, and the England that's described here feels like it was preserved in 1930s amber.

As I said before, Hone is not so simple a writer. Looked at from another angle the novel is a rubbishing of the myths of England's "green and pleasant land." The character of Clare is at the heart of the story, and her origin myth, as it were, is revealed to be part of a shocking and brutal crime committed by one one of those adventurer-explorers so beloved in British history. And the country house, that ark of Albion, is kept alive by American money and is actually a kind of open prison for Alice (a raging anglophile), who turns out to be as mad as a hatter. Behind the false front of cream teas, cricket pitches, rolling green fields speckled with snowy white sheep, and stately, ancestral homes lies violence, greed and insanity.

I'm still having the brilliant vs bonkers argument with myself, but on the whole I'd have to say that The Valley of the Fox is just a little too quirky for its own good. The prose is always first-rate, but the story's demented plot twists finally move past farfetched and into silliness. It's still worth reading, but it's not in the same league as Hone's previous Marlow novels, The Private Sector and The Oxford Gambit. And one last thing: a couple of elements in this novel bear a striking similarity to Italo Calvino's The Baron in the Trees, which I reviewed earlier this summer. It's not a case of plagiarism, but it's hard not to think that Calvino's eccentric novel might have inspired Hone's equally odd book.

Saturday, August 31, 2013

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

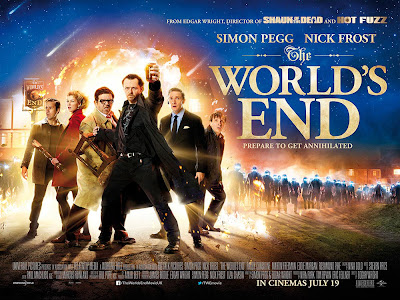

Film Review: The World's End (2013)

I'll get the most important item out of the way first: this is the least funny of the so-called Cornetto Trilogy by the triumvirate of actors Simon Pegg and Nick Frost, and director Edgar Wright. However, that still makes it a better than average comedy. It's not as LOL funny as Shaun of the Dead or Hot Fuzz, but it's always amusing and it's hands down the raunchiest, funniest, most violent episode of Dr Who ever. The thumbnail plot description is that five old friends (sort of) reunite for a pub crawl in a small English town and have a spot of bother with some aliens. If there's a link between all three films in the trilogy it's that in each case our heroes end up in a life and death struggle with the middle-class locals. There may be a Marxist, beware-the-bourgeoisie message in there somewhere, and if so I'm all for it.

Even though The World's End isn't a great comedy, it deserves respect for being smartly written. Unlike the normal run of comedies this is a film that's trying to get its laughs with wit and wordplay. The jokes don't always work, or they just raise a smile, but it's nice to see a comedy that isn't aggressively stupid or mining the gross-out vein, which, of course, means Adam Sandler's nowhere in sight. And what does it say about the current state of action films that this middling budget comedy shows more style and flair in the running, jumping, thumping people department than most films with ten times its budget.

If there's one person who deserves special mention here it's Simon Pegg. It's no surprise he's funny, but it's becoming clearer with every film he does that he's also a fine actor. His character in the film is loud, brash and obnoxious, but the subtle way in which Pegg uses facial expressions to show thoughts and emotions is outstanding. And his vocal work is even better. This guy has a great voice; listen carefully and you hear an actor you should be taking a stab at the St. Crispin's Day speech from Henry V. In relation to this, watch the film's final scene, which features Pegg, and take note of what looks like a reference to King Arthur. The only footnote I'd add to Pegg's performance is that his character of Gary King, and even his performance, seems slightly modeled on Rik Mayall's turn as Richie Richards in the Brit sitcom Bottom. That's not a bad thing. So here's hoping the next chapter in the Cornetto cycle of films is Macbeth. Now there's a chap who had some trouble with the locals.

Even though The World's End isn't a great comedy, it deserves respect for being smartly written. Unlike the normal run of comedies this is a film that's trying to get its laughs with wit and wordplay. The jokes don't always work, or they just raise a smile, but it's nice to see a comedy that isn't aggressively stupid or mining the gross-out vein, which, of course, means Adam Sandler's nowhere in sight. And what does it say about the current state of action films that this middling budget comedy shows more style and flair in the running, jumping, thumping people department than most films with ten times its budget.

If there's one person who deserves special mention here it's Simon Pegg. It's no surprise he's funny, but it's becoming clearer with every film he does that he's also a fine actor. His character in the film is loud, brash and obnoxious, but the subtle way in which Pegg uses facial expressions to show thoughts and emotions is outstanding. And his vocal work is even better. This guy has a great voice; listen carefully and you hear an actor you should be taking a stab at the St. Crispin's Day speech from Henry V. In relation to this, watch the film's final scene, which features Pegg, and take note of what looks like a reference to King Arthur. The only footnote I'd add to Pegg's performance is that his character of Gary King, and even his performance, seems slightly modeled on Rik Mayall's turn as Richie Richards in the Brit sitcom Bottom. That's not a bad thing. So here's hoping the next chapter in the Cornetto cycle of films is Macbeth. Now there's a chap who had some trouble with the locals.

Saturday, August 24, 2013

Book Review: The Fortress of Solitude (2003) by Jonathan Lethem

The first half of this novel constitutes one of the best coming of age stories I've ever read. All the fears, insecurities, loopy fantasies, and feverish joys taken in the simplest of achievements or pleasures--everything that makes childhood and adolescence such a tortuous and ecstatic time--is in here. Dylan Ebdus is the boy who comes of age, and he does so in Brooklyn in the 1970s. His Brooklyn is not the gentrified, hipster zone it's now become. Dylan's Brooklyn is where stickball and stoopball are still played, and racial tension is out in the open at all times. Dylan's family is one of the few white families in the area, although the first hints of future gentrification are visible. His best friend is Mingus Rude, a black boy whose father, Barrett Rude Jr., was once a semi-successful soul singer. Dylan and Mingus bond over a shared love of comic books and superheroes, and, later, graffiti. Dylan's father, Abraham, is an artist and experimental filmmaker. His wife, Rachel, abandons the family when Dylan is about thirteen.

Dylan's young life suffers from two torments: his mother abandoning him and the bullying he suffers as virtually the only white kid in an predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhood. Mingus provides some protection from bullying, but Dylan, as the title suggests, spends his youth living in various kinds of solitude, some of his own making, some forced on him by his environment and his peers. As I said, this half of the novel is a brilliant, etched in acid portrait of the highs, lows and the boring bits in-between that constituted the life of someone growing up in the early 1970s. I speak from experience.

The second half of the novel almost goes completely off the rails. The action has jumped forward to the 1990s and Dylan has become a music journalist living in California. Abraham has a new wife and is a semi-celebrity as an illustrator of SF novels. Mingus and his father are both drug addicts, and Mingus has been in and out of jail multiple times. Dylan has not been able to put his troubled childhood behind him, and feels that he has to do something for Mingus, who is in a prison in upstate New York.

There are a lot of different problems with this section of the book. The major one is the depiction of the black characters. With one minor exception all of them are criminals, drug addicts or derelicts. Lethem writes about them with great sensitivity and insight, but the unvarnished truth is that they only exist in the story as devices to give depth and definition to Dylan. Black poverty and criminality ends up being used to show Dylan's feelings of guilt and anger; they act as a backdrop to throw Dylan's state of mind and existential conflicts into focus. Lethem doesn't bother to tell us why his black characters have all ended up down and out, there's no attempt to put their downfall in a social context, it simply happens to every black person in the novel. It's certainly true that the coke and crack epidemics of the '80s and '90s took a heavy toll in the black community, but it was still only a minority of the black population that was affected to the degree we see here. I may be off-base with my take on this issue, but if I imagine an African American reading this novel I can only think he or she would be deeply offended. It's significant that the only white character who takes a criminal path (a nerdy kid named Arthur) eventually manages to rehabilitate himself into a pocket-sized property tycoon. Blacks aren't allowed second acts in this novel. The long and the short of it is that black suffering is being exploited for dramatic purposes.

Another problem is that the story loses focus once Dylan is an adult. We follow him as he reconnects with his father; meets an egregious lawyer; fights with his (black) girlfriend; looks for his mother; pitches a film project at Dreamworks Studios; and attempts to rescue Mingus from prison. Lethem's writing also suffers. The scenes with his girlfriend are filled with the prickly banalities one normally hears in self-consciously serious primetime TV dramas, and the scene at the Dreamworks offices is a tired and generic parody of a Hollywood meeting. The "rescue" of Mingus can either be looked at as a white liberal guilt fantasy trip or a disastrous decision to mix in some magic realism. Either way it doesn't work.

Even with all the problems in the second half this remains a mostly excellent novel. Lethem's prose is always daring, energetic and innovative, and he deserves credit for writing a novel that dares to show that there's a class system in America. But I'd really, really like to hear what African American readers and reviewers have to say about this book, so if someone can point me towards any online commentary along those lines, please leave a comment. And for a very alternative view of the black experience in Brooklyn, check out my review of Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall.

Dylan's young life suffers from two torments: his mother abandoning him and the bullying he suffers as virtually the only white kid in an predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhood. Mingus provides some protection from bullying, but Dylan, as the title suggests, spends his youth living in various kinds of solitude, some of his own making, some forced on him by his environment and his peers. As I said, this half of the novel is a brilliant, etched in acid portrait of the highs, lows and the boring bits in-between that constituted the life of someone growing up in the early 1970s. I speak from experience.

The second half of the novel almost goes completely off the rails. The action has jumped forward to the 1990s and Dylan has become a music journalist living in California. Abraham has a new wife and is a semi-celebrity as an illustrator of SF novels. Mingus and his father are both drug addicts, and Mingus has been in and out of jail multiple times. Dylan has not been able to put his troubled childhood behind him, and feels that he has to do something for Mingus, who is in a prison in upstate New York.

There are a lot of different problems with this section of the book. The major one is the depiction of the black characters. With one minor exception all of them are criminals, drug addicts or derelicts. Lethem writes about them with great sensitivity and insight, but the unvarnished truth is that they only exist in the story as devices to give depth and definition to Dylan. Black poverty and criminality ends up being used to show Dylan's feelings of guilt and anger; they act as a backdrop to throw Dylan's state of mind and existential conflicts into focus. Lethem doesn't bother to tell us why his black characters have all ended up down and out, there's no attempt to put their downfall in a social context, it simply happens to every black person in the novel. It's certainly true that the coke and crack epidemics of the '80s and '90s took a heavy toll in the black community, but it was still only a minority of the black population that was affected to the degree we see here. I may be off-base with my take on this issue, but if I imagine an African American reading this novel I can only think he or she would be deeply offended. It's significant that the only white character who takes a criminal path (a nerdy kid named Arthur) eventually manages to rehabilitate himself into a pocket-sized property tycoon. Blacks aren't allowed second acts in this novel. The long and the short of it is that black suffering is being exploited for dramatic purposes.

Another problem is that the story loses focus once Dylan is an adult. We follow him as he reconnects with his father; meets an egregious lawyer; fights with his (black) girlfriend; looks for his mother; pitches a film project at Dreamworks Studios; and attempts to rescue Mingus from prison. Lethem's writing also suffers. The scenes with his girlfriend are filled with the prickly banalities one normally hears in self-consciously serious primetime TV dramas, and the scene at the Dreamworks offices is a tired and generic parody of a Hollywood meeting. The "rescue" of Mingus can either be looked at as a white liberal guilt fantasy trip or a disastrous decision to mix in some magic realism. Either way it doesn't work.

Even with all the problems in the second half this remains a mostly excellent novel. Lethem's prose is always daring, energetic and innovative, and he deserves credit for writing a novel that dares to show that there's a class system in America. But I'd really, really like to hear what African American readers and reviewers have to say about this book, so if someone can point me towards any online commentary along those lines, please leave a comment. And for a very alternative view of the black experience in Brooklyn, check out my review of Brown Girl, Brownstones by Paule Marshall.

Saturday, August 17, 2013

The Noisy New World of Silent Movies

|

| Were he alive today he'd be playing Captain Jack Sparrow |

The silent movie was the first art form to become instantly popular in virtually all cultures and countries. Silent films told simple stories in bold, broad visual strokes, with a minimal amount of dialogue and plot information provided through title cards. And to cue and hype the audience's emotional reactions, the films had a musical soundtrack provided by an in-house pianist or even a symphony in larger theatres. Language was no barrier to the enjoyment of silent films; the stories were classic and familiar tales of love lost and gained; heroes on quests and adventures; and lots and lots of slapstick. Special effects took the form of dangerous stunts, elaborate sets, and herds of extras. Whether you lived in America or Armenia, silent films were a common denominator of enjoyment and fascination.

And now we're in the second age of silent movies. Today's silent films, represented by titles like Pacific Rim, Elysium, and franchises like Transformers, the Die Hard films and James Bond, qualify as silents in my book because, like the films of Fairbanks and Keaton, dialogue and complex storytelling is kept to an absolute minimum in order to tell stories easily and quickly, and thus reach a wider global audience. Films like The Last Stand or White House Down might just as well have title cards to handle the dialogue and plot, because the real point of these films is to throw up a wall of noise, SFX, and hyper-fast action.

Thoughtful, complex, more well-crafted films are still being made, but more and more they appeal only to specific national audiences and the international arthouse crowd. Thanks to burgeoning middle-classes in China, India, Brazil and a variety of other countries, the foreign box office has never been more important to Hollywood. In order to reach that audience efficiently, Hollywood has dumbed down its blockbusters so that nothing's lost in translation when a film is shown in Shanghai or Warsaw or Bangalore. All audiences understand and enjoy slapstick, violence, eye-popping CGI effects, and the simple storylines that propel these big budget films from one climactic moment to the next. And in case people don't know how to react, film composers like Hans Zimmer, John Williams and James Horner are on hand to lay on the symphonic bombast or syrup.

A good example of this new style of filmmaking comes from director Neil Blomkamp. His District 9 (2009) had a clever SF concept, told its story from multiple points of view, and featured subtle characterization and social commentary. It was modestly budgeted at $30m. Blomkamp's recently released Elysium cost $100m and is as direct and subtle as a four-panel Dick Tracy comic strip. Everything that made Blomkamp's first film different and original has been tossed aside in favour of generic action elements, a pounding score, and a plot so basic three title cards would probably be sufficient to describe it. This makes it perfect for the international market.

In what may or may not be an unrelated development, a lot of these films are being directed by people whose first language isn't English. The Last Stand, Pacific Rim, and White House Down were directed by, respectively, a Korean, a Mexican and a German. None of these films started out with good scripts, but it's clear that all three directors have a tin ear for dialogue: line readings in these films are odd or bad, and attempts at humor inevitably fall flat. This isn't really the fault of the directors. If you're not familiar with a language how can you gauge whether dialogue has been delivered well or not? And another culture's humor is extraordinarily difficult to figure out. I wouldn't expect Martin Scorsese to do a good job of directing a Bollywood comedy, so why would a Korean or German be likely to succeed with an English language film? Just this week I heard an interview with Danish director Nicholas Winding Refn (Drive, Only God Forgives) in which he said that the reason there's so little dialogue in his films is that he's not comfortable writing in English. He also said that actor Ryan Reynolds had to write all the dialogue in Only God Forgives that involved swearing. Refn felt completely lost when it came to cursing in English. Swearing, like humor, is unique to each culture and difficult for outsiders to acquire fluency in. I think a lot of other foreign directors, if they were being honest, would admit that, like Refn, they aren't comfortable working in English. But who's going to turn down a Hollywood paycheque?

There's nothing wrong with purely visual storytelling if the visuals are used to describe character, advance the plot, or create a mood or emotion that dialogue simply can't describe. Badlands by Terence Malick is a perfect example of this kind of film, and a more extreme example would be the brilliant Italian film Le Quattro Volte. There may be signs that the English-speaking world is growing dissatisfied with these noisy, shooty, blow-everything-up blockbusters. Epics like Man of Steel, Pacific Rim and The Lone Ranger have underperformed in North America. Many critics have said it's because audiences are getting tired of the same kind of movie always being offered up, but I'm thinking it's because filmgoers are beginning to realize that these blockbusters are just too simple-minded and primitive. Why not stay home and watch something smart on HBO or AMC? In 1929 the "talkies" replaced the silents, and in the last decade or so it looks like the talkies are being superseded by what I'm going to call the "shouties."

Monday, August 12, 2013

Film Review: Elysium (2013)

The quickest way to review Elysium would be to repost my Pacific Rim review and simply substitute one title for the other. In its fundamentals, Elysium is just as bad as Pacific Rim and in the same ways: the plot is simple enough for an eight-year-old to follow; the dialogue is never better than banal; and the action elements are tedious and repetitive. So I'll just point out some of Elysium's more unusual and egregious errors.

First off, if you're going to set a film 140 years in the future you might want to do some world-building, show us how radically things have changed in more than a century. Someone should have told Neil Blomkamp, the director and scriptwriter, that one of main delights of SF is imagining future worlds. In Elysium's future everyone still has the same clothes, hair, and slang. And plasma TVs are still around? Seriously? We're even driving the same cars! The only thing that's noticeably different in this future is that Jodie Foster has become a really awful actor. She plays a villain, and does so with a staggering amount of facial tics and twitches, an accent that wanders around Europe and the eastern US, and some line readings that wouldn't pass muster in a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. Sharlto Copley almost matches Foster's ineptitude as a thuggish killer. And his character really is cartoonish; it's surprising Blomkamp didn't go the whole nine yards and give him horns and a forked tail.

What's most disappointing about Elysium is that Blomkamp's District 9 was such a brilliant film, deftly combining an intriguing, well-realized SF concept with drama, action and humour. It was the whole package. Elysium feels like it was quickly cobbled together by a hack director who was given a script that was rejected by the SyFy Channel. This is lazy, unimaginative filmmaking at its worst. But that's the way things are this year in the cinemas, and I'll have a post about the reasons why in the near future.

First off, if you're going to set a film 140 years in the future you might want to do some world-building, show us how radically things have changed in more than a century. Someone should have told Neil Blomkamp, the director and scriptwriter, that one of main delights of SF is imagining future worlds. In Elysium's future everyone still has the same clothes, hair, and slang. And plasma TVs are still around? Seriously? We're even driving the same cars! The only thing that's noticeably different in this future is that Jodie Foster has become a really awful actor. She plays a villain, and does so with a staggering amount of facial tics and twitches, an accent that wanders around Europe and the eastern US, and some line readings that wouldn't pass muster in a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. Sharlto Copley almost matches Foster's ineptitude as a thuggish killer. And his character really is cartoonish; it's surprising Blomkamp didn't go the whole nine yards and give him horns and a forked tail.

What's most disappointing about Elysium is that Blomkamp's District 9 was such a brilliant film, deftly combining an intriguing, well-realized SF concept with drama, action and humour. It was the whole package. Elysium feels like it was quickly cobbled together by a hack director who was given a script that was rejected by the SyFy Channel. This is lazy, unimaginative filmmaking at its worst. But that's the way things are this year in the cinemas, and I'll have a post about the reasons why in the near future.

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Book Review: Going to the Dogs (1931) by Erich Kastner

Germany during the Weimar Republic is one of those times and places in history that has a peculiar hold on the popular imagination. We see it as being uniquely decadent, revolutionary, perverse, artistic, uninhibited, violent, febrile and doom-laden; it's where the 19th and 20th centuries met in a head-on collision that we're still picking up the pieces from. Based on this novel, written only a few years before the Nazis took power, that's exactly what those times were like. And here's how Jacob Fabian, the novel's protagonist, describes Europe's mood:

"Europe had been let out of school. The teachers were gone, the time-table had vanished. The old continent would never get through the syllabus. Never get through any syllabus!"

Erich Kastner was one of Germany's most celebrated intellectuals; an accomplished poet, literary critic and the author of the hugely successful children's book Emil and the Detectives. Going to the Dogs (published as Fabian in Germany) is Kastner's literary snapshot of life in Berlin in the late 1920s. Kastner's hero is Jacob Fabian, a thirty-two-year-old copywriter who wanders the city witnessing how Berliners react to the stresses of the times. What we glean from Fabian's picaresque adventures is that Germans staved off despair and angst by living emphatically and sensuously in the present. Fabian's Berlin is filled with sexually voracious men and women who crowd together in brothels or places like the Anonymous Club, where lunatics are hired to entertain the patrons. Yes, this fictional Berlin easily meets the weirdness quota one would expect from a story set in Weimar Germany.

What makes the novel resonate with a modern reader is Fabian's humanity, his halting, reluctant desire to be something better than he is. Fabian is both a victim and a participant in the downfall of society, and he's very aware that worse is to come. As grim as the background to this novel is, this isn't a grim novel. Kastner has a spritely wit and cynicism that makes the downward trajectory of German society entertaining, if not palatable. Several fine novels of the 1930s deal with the feeling of imminent doom hanging over Europe--George Orwell's Coming Up For Air, Eric Ambler's Journey Into Fear, Aldous Huxley's Eyeless In Gaza--and this one certainly belongs in the same class.

"Europe had been let out of school. The teachers were gone, the time-table had vanished. The old continent would never get through the syllabus. Never get through any syllabus!"

Erich Kastner was one of Germany's most celebrated intellectuals; an accomplished poet, literary critic and the author of the hugely successful children's book Emil and the Detectives. Going to the Dogs (published as Fabian in Germany) is Kastner's literary snapshot of life in Berlin in the late 1920s. Kastner's hero is Jacob Fabian, a thirty-two-year-old copywriter who wanders the city witnessing how Berliners react to the stresses of the times. What we glean from Fabian's picaresque adventures is that Germans staved off despair and angst by living emphatically and sensuously in the present. Fabian's Berlin is filled with sexually voracious men and women who crowd together in brothels or places like the Anonymous Club, where lunatics are hired to entertain the patrons. Yes, this fictional Berlin easily meets the weirdness quota one would expect from a story set in Weimar Germany.

What makes the novel resonate with a modern reader is Fabian's humanity, his halting, reluctant desire to be something better than he is. Fabian is both a victim and a participant in the downfall of society, and he's very aware that worse is to come. As grim as the background to this novel is, this isn't a grim novel. Kastner has a spritely wit and cynicism that makes the downward trajectory of German society entertaining, if not palatable. Several fine novels of the 1930s deal with the feeling of imminent doom hanging over Europe--George Orwell's Coming Up For Air, Eric Ambler's Journey Into Fear, Aldous Huxley's Eyeless In Gaza--and this one certainly belongs in the same class.

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Book Review: The Doll Princess (2012) by Tom Benn

The Doll Princess emphatically check marks the crime fiction box labeled "noir," and does so with energy, wit and style. These days noir is shorthand for a setting that's exceedingly grim; visceral and grisly acts of violence; and sex that's frequent and sometimes brutal. Having praised it, I now have to, if not damn it, at least laugh at it a little. A lot of modern noir crime novels have a tendency to wallow in grittiness and sordidness to a degree that becomes, well, risible. You reach a point in some of these novels where you're fondly imagining Graham Chapman's army officer character from Monty Python suddenly intruding on the action to declare that what began as a nice hard-boiled crime story has just gotten "too silly." This novel sometimes strays over the line into noir silliness, but on the whole it's a solidly entertaining thriller.

The Doll Princess, like other novels in the noir field by authors such as Ray Banks, Declan Hughes and Ken Bruen, makes a determined effort to paint its fictional world in a palette consisting of blacks and, well, more blacks. The plot is a minor reworking of the Michael Caine film Get Carter. Henry Bane, an enforcer for a Manchester crime boss, learns that an ex-girlfriend from his teenage years has been found murdered. Bane investigates. For no clear reason the action is set in 1996, shortly after a deadly IRA bombing in the city. The IRA doesn't factor into the plot, so I'm left wondering why we're in 1996. Was that a particularly noir period in Manchester's recent history? Along the way we encounter a sex ring, a new kind of street drug, and bloodthirsty Serbian gangsters. We also get some spiky British gangland dialogue, and our hero, like any hard-boiled gumshoe from the 1930s, takes a beating or two but keeps on coming, dropping wisecracks along the way. Bane is what holds the novel together. Like Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, Bane moves in a noir world, but he himself holds on to some humanity; he's bad, but he's better than those around him. A lesser writer would have made Bane as dark and disturbed as the milieu he moves in. What I could have done without was so much violence being directed towards women, and a few too many laddish descriptions of sex and female body parts. And Serbian gangsters? Really? As villains, Serbian baddies have become the modern cliche equivalent of gypsy horse thieves. Be warned that all the dialogue is written in a Manchester accent--no concessions for non-Mancunians. Thanks to having a mother who watched Coronation Street religiously when I was kid, I coped quite well. I just imagined I was listening to Stan and Hilda Ogden.

Reviews of noir crime novels routinely describe them as gritty and realistic, often making disparaging references to the Midsomer Murders end of the crime fiction spectrum. In truth, noir mysteries are every bit as divorced from reality as a story set in Chipping Badger featuring a killer poisoning people in order to win a raffle at the church fete. The latter kind of mystery, with its warm and fuzzy characters and lashings of cream teas, is a mild literary opiate for middle-class readers who like their fictional crime to come in a neat, attractive package with all the appropriate government warning labels. Noir is a mild amphetamine for middle-class readers who like to think their fictional crime choice gives them a kind of vicarious street cred; it allows them to feel that, in a very small way, they know what life on the edge is like. These readers are looking for, as the saying goes, "a bit of rough." At least writers of cosy mysteries are aware that they're peddling pablum, and none of them ever argue that they should be winning literary awards. The noir writers, on the other hand, take themselves very seriously indeed. They often grumble about not making the Booker Prize longlist. But the darker and nastier they make their novels, the more they stray into a noir fantasy land that's an exercise in willful, cranky dystopianism.

The Doll Princess, like other novels in the noir field by authors such as Ray Banks, Declan Hughes and Ken Bruen, makes a determined effort to paint its fictional world in a palette consisting of blacks and, well, more blacks. The plot is a minor reworking of the Michael Caine film Get Carter. Henry Bane, an enforcer for a Manchester crime boss, learns that an ex-girlfriend from his teenage years has been found murdered. Bane investigates. For no clear reason the action is set in 1996, shortly after a deadly IRA bombing in the city. The IRA doesn't factor into the plot, so I'm left wondering why we're in 1996. Was that a particularly noir period in Manchester's recent history? Along the way we encounter a sex ring, a new kind of street drug, and bloodthirsty Serbian gangsters. We also get some spiky British gangland dialogue, and our hero, like any hard-boiled gumshoe from the 1930s, takes a beating or two but keeps on coming, dropping wisecracks along the way. Bane is what holds the novel together. Like Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, Bane moves in a noir world, but he himself holds on to some humanity; he's bad, but he's better than those around him. A lesser writer would have made Bane as dark and disturbed as the milieu he moves in. What I could have done without was so much violence being directed towards women, and a few too many laddish descriptions of sex and female body parts. And Serbian gangsters? Really? As villains, Serbian baddies have become the modern cliche equivalent of gypsy horse thieves. Be warned that all the dialogue is written in a Manchester accent--no concessions for non-Mancunians. Thanks to having a mother who watched Coronation Street religiously when I was kid, I coped quite well. I just imagined I was listening to Stan and Hilda Ogden.

Reviews of noir crime novels routinely describe them as gritty and realistic, often making disparaging references to the Midsomer Murders end of the crime fiction spectrum. In truth, noir mysteries are every bit as divorced from reality as a story set in Chipping Badger featuring a killer poisoning people in order to win a raffle at the church fete. The latter kind of mystery, with its warm and fuzzy characters and lashings of cream teas, is a mild literary opiate for middle-class readers who like their fictional crime to come in a neat, attractive package with all the appropriate government warning labels. Noir is a mild amphetamine for middle-class readers who like to think their fictional crime choice gives them a kind of vicarious street cred; it allows them to feel that, in a very small way, they know what life on the edge is like. These readers are looking for, as the saying goes, "a bit of rough." At least writers of cosy mysteries are aware that they're peddling pablum, and none of them ever argue that they should be winning literary awards. The noir writers, on the other hand, take themselves very seriously indeed. They often grumble about not making the Booker Prize longlist. But the darker and nastier they make their novels, the more they stray into a noir fantasy land that's an exercise in willful, cranky dystopianism.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)