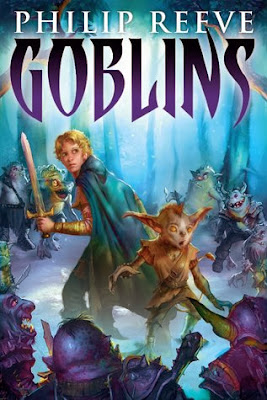

In the field of steampunk literature (Teen division), Philip Reeve rules with a brass and mahogany fist. His seven-volume Mortal Engines series is simply one of the best achievements in imaginative writing in the last few decades. With Goblins he's taking a crack at fantasy (Young Adult regiment), and if the result isn't likely to be as seminal as Mortal Engines, it's still head and shoulders above the usual standard of YA fantasy titles.

Goblins could be described as fan fiction in the sense that Reeve has taken a sideways look at Tolkien's Middle-Earth and decided that someone needs to write a humorous story from the the point of view of the goblins. Reeve's goblins are foul and fell creatures, but since they're raised from birth (hatched, actually) according to the maxim of spare the mallet, spoil the goblin, one could say that it's a case of nurture rather than nature that accounts for their anti-social behavior. The goblins live in Clovenstone, a massive and ruined city/fortress that was once ruled by the dreaded Lych Lord. They spend most of their time beating up on each other, with the occasional raid on human settlements to relieve the monotony. Skarper, a young goblin, learns to read, which makes him unique amongst goblins, but it also leads to him being catapulted off the battlements of Clovenstone after an unwise display of his literacy. He then meets Henwyn, a teenage boy and wannabe hero who's left home after an unfortunate cheesemaking accident. The two join up and experience more adventures than is good for their health.

While the landscape and architecture of Goblins has echoes of Tolkien, and it's style and comic tone has resounding echoes of Terry Pratchett, the wit and imagination is all Reeve. The world-building in Goblins is first rate. With a minimum of fuss and verbiage, Reeve is able to create a rich, interesting world peopled (creatured?) with cloud maidens, twiglings, boglins, and giants that get smaller as they get older. I compared Reeve to Pratchett in terms of humor but what both share is a distinctly British form of humor that revolves around the subversion of anything or anyone that seems overly proud, serious or powerful; the self-important and mighty typically find themselves humbled or embarrassed by common sense, the unavoidable facts of life, and bureaucratic inflexibility. Think of it as the revenge of middle-class values. It's a comic philosophy that seems in tune with thoroughly British concepts like "muddling through" and "the Dunkirk spirit." It's also the perfect form of humor for "a nation of shopkeepers."In contrast, American humor shows the high and mighty being flattened by anarchic proletarian violence: think the Three Stooges and Adam Sandler.

Goblins is the first in a projected trilogy, and I'll be there for each one of them. The only thing I ask for are some maps. I want a map of Clovenstone. Maps, please.

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Sunday, October 27, 2013

Book Review: The Barbed-Wire University (2011) by Midge Gillies

There have been dozens and dozens of Second World War memoirs written by former Allied POWs that revolve around escapes of various kinds. This book attempts to describe life as it was lived by the vast majority of POWs, the ones who weren't busily engaged in tunneling, forging documents, crafting disguises, or, in the case of prisoners at Colditz, building a glider for an airborne escape. Gillies does a decent job, but there are some strange gaps that make this a less than complete history. But first the good bits:

One thing that comes out of this history is that the Nazis were strangely more humane towards their POWs (the English-speaking ones, at least) than they were to, well, everyone else. Life in a POW camp in Germany wasn't pleasant, especially as food become scarce in the last months of the war, but on balance it was a dull but tolerable existence. Red Cross parcels came through on a regular basis, as did the occasional parcel from loved ones back home. The prisoners kept themselves amused or stimulated with sports, hobbies and informal educational courses in everything from languages to automotive engineering. A sign of how relatively civilized life as a POW was can be gauged from the fact that prisoners were able to take correspondence courses from English universities and "graduate" with degrees. That's right, being a POW in German hands could actually lead to career advancement. The situation of POWs in the Far East was radically different. The Japanese treated prisoners with a uniform brutality that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths. This was one of the great war crimes of WW II and if nothing else Gillies' book is a reminder of an institutionalized atrocity that went largely unpunished.

The inventiveness and ingenuity of POWs is one of the highlights of the book. Even with the most minimal of raw materials POWs were able to create everything from drugs to radios to, yes, a glider. Not only is this a testament to their creativity, it's also makes one realize that a similar group of modern men would probably be utterly hapless--our grandfathers were handy, we're computer literate. No prize for guessing which group would cope better in a POW camp.

The book's faults are most apparent at the end. Gillies doesn't discuss whether POWs, especially those in Japanese hands, took any reprisals against their former captors. There's a brief mention of POWs in a German camp killing a couple of SS men, but it begs the question of whether this was a common event or not. And the question of whether any Germans or Japanese were tried for war crimes for their treatment of prisoners is ignored entirely. In fact, hundreds of Japanese were tried for war crimes against POWs and many were imprisoned or executed. And yet another subject that gets no attention is that of POWs who collaborated with their captors. Did it happen? And, if so, how often and to what degree? The worst oversight Gillies makes is announced in the book's title, the full version of which is The Barbed-Wire University: The Real Lives of Allied Prisoners of War in the Second World War. That's funny, I thought the Russians were one of the Allies. There is absolutely no description of life for Russian POWs. There are a few, stray mentions of them, but the title of the book should really be changed to the Real Lives of British Prisoners. It also would have been useful to be given a rough idea of how the Allies dealt with German POWs. If you've never read anything about POW life in WW II this book serves as a low-calorie introduction, albeit from an almost entirely British perspective, but clearly there's room for a more balanced and comprehensive history of the subject.

One thing that comes out of this history is that the Nazis were strangely more humane towards their POWs (the English-speaking ones, at least) than they were to, well, everyone else. Life in a POW camp in Germany wasn't pleasant, especially as food become scarce in the last months of the war, but on balance it was a dull but tolerable existence. Red Cross parcels came through on a regular basis, as did the occasional parcel from loved ones back home. The prisoners kept themselves amused or stimulated with sports, hobbies and informal educational courses in everything from languages to automotive engineering. A sign of how relatively civilized life as a POW was can be gauged from the fact that prisoners were able to take correspondence courses from English universities and "graduate" with degrees. That's right, being a POW in German hands could actually lead to career advancement. The situation of POWs in the Far East was radically different. The Japanese treated prisoners with a uniform brutality that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths. This was one of the great war crimes of WW II and if nothing else Gillies' book is a reminder of an institutionalized atrocity that went largely unpunished.

The inventiveness and ingenuity of POWs is one of the highlights of the book. Even with the most minimal of raw materials POWs were able to create everything from drugs to radios to, yes, a glider. Not only is this a testament to their creativity, it's also makes one realize that a similar group of modern men would probably be utterly hapless--our grandfathers were handy, we're computer literate. No prize for guessing which group would cope better in a POW camp.

The book's faults are most apparent at the end. Gillies doesn't discuss whether POWs, especially those in Japanese hands, took any reprisals against their former captors. There's a brief mention of POWs in a German camp killing a couple of SS men, but it begs the question of whether this was a common event or not. And the question of whether any Germans or Japanese were tried for war crimes for their treatment of prisoners is ignored entirely. In fact, hundreds of Japanese were tried for war crimes against POWs and many were imprisoned or executed. And yet another subject that gets no attention is that of POWs who collaborated with their captors. Did it happen? And, if so, how often and to what degree? The worst oversight Gillies makes is announced in the book's title, the full version of which is The Barbed-Wire University: The Real Lives of Allied Prisoners of War in the Second World War. That's funny, I thought the Russians were one of the Allies. There is absolutely no description of life for Russian POWs. There are a few, stray mentions of them, but the title of the book should really be changed to the Real Lives of British Prisoners. It also would have been useful to be given a rough idea of how the Allies dealt with German POWs. If you've never read anything about POW life in WW II this book serves as a low-calorie introduction, albeit from an almost entirely British perspective, but clearly there's room for a more balanced and comprehensive history of the subject.

Monday, October 21, 2013

Film Review: Captain Phillips (2013)

The first thing that struck me about Captain Phillips is that there is no such thing as a closeup shot that's too close for director Paul Greengrass. He's made his name with docudramas such as Bloody Sunday and United 93, and he brought a rigorously documentary look to two installments in the Bourne franchise (Supremacy and Ultimatum). His cameras are almost always handheld and usually kept within bumping distance of the actors. Captain Phillips is more, much more, of the same. It's yet another docudrama, this time about the capture by Somali pirates of a US container ship off the coast of Somalia in 2009. The titular captain was held hostage by the four pirates in a lifeboat after they abandoned the cargo ship, and after several tense days Phillips was rescued by US Navy Seals.

That's the nuts and bolts of the story, and Greengrass tells it in a resolutely nuts and bolts style. There's no superfluous action or characterization on display here; everything's stripped down to the basics, much like the cargo ship Maersk Alabama, which is nothing more than a floating steel box with a bunch of moving parts. Action-thrillers don't get sparer or more stripped-down than this one. The closeups are what really create the tension in the story because the faces that are zeroed in on are almost always expressing anguish, anxiety or sheer terror. In some respects Captain Phillips is simply a very big budget version of those docudrama TV shows in which various disasters or bizarre murder cases are recreated using actors not quite good enough for infomercials. But when you've got millions to play with you can hire Tom Hanks.

Hanks is the glue that holds this film together. He's played Everyman roles like this one before, but the difference here is that he can't show a spark of his trademark wit or charm. Phillips is all business, which is established early on with some tetchy comments he makes towards the crew about lengthy coffee breaks. There's no glamour in this character, no heroics, just a dogged determination to do the right thing and to do it by the book. Like Phillips, the crew are shown doing their jobs and nothing more; no joking around, no longing looks at pictures of loved ones, just a bunch of guys caught in the wrong place at the wrong time and really, really upset about it. The dispassionate portrayal of Phillips and his crew members certainly adheres to the film's documentary aesthetic, but it also takes some of the edge off the tension. Phillips & Co. are presented to us as depersonalized, maritime drones. A touch more character development might have made their plight more dramatic. Interestingly, the four pirates are given more of a back story than the crew. The script makes it clear that the "pirates" are living in poverty, taking the only paying job available to the them. The real money is made by the warlords and tribal elders who own the boats. The pirates who actually board the ships are working for minimum wage.

Captain Phillips is brutally effective and efficient in telling its story, but it lacks a certain humanity that would have made it really memorable. It's telling that the most human and intense moment in the film comes at the very end, shortly after Phillips has been rescued. He's being examined by a Navy doctor and as he tries to answer the doctor's questions he suffers a nervous breakdown. It's not a showy or hammy piece of acting by Hanks, but it's stone cold brilliant, and if they awarded acting Oscars for two minute film segments he'd have it nailed. It's also the one scene in the film that will probably linger in your memory.

That's the nuts and bolts of the story, and Greengrass tells it in a resolutely nuts and bolts style. There's no superfluous action or characterization on display here; everything's stripped down to the basics, much like the cargo ship Maersk Alabama, which is nothing more than a floating steel box with a bunch of moving parts. Action-thrillers don't get sparer or more stripped-down than this one. The closeups are what really create the tension in the story because the faces that are zeroed in on are almost always expressing anguish, anxiety or sheer terror. In some respects Captain Phillips is simply a very big budget version of those docudrama TV shows in which various disasters or bizarre murder cases are recreated using actors not quite good enough for infomercials. But when you've got millions to play with you can hire Tom Hanks.

Hanks is the glue that holds this film together. He's played Everyman roles like this one before, but the difference here is that he can't show a spark of his trademark wit or charm. Phillips is all business, which is established early on with some tetchy comments he makes towards the crew about lengthy coffee breaks. There's no glamour in this character, no heroics, just a dogged determination to do the right thing and to do it by the book. Like Phillips, the crew are shown doing their jobs and nothing more; no joking around, no longing looks at pictures of loved ones, just a bunch of guys caught in the wrong place at the wrong time and really, really upset about it. The dispassionate portrayal of Phillips and his crew members certainly adheres to the film's documentary aesthetic, but it also takes some of the edge off the tension. Phillips & Co. are presented to us as depersonalized, maritime drones. A touch more character development might have made their plight more dramatic. Interestingly, the four pirates are given more of a back story than the crew. The script makes it clear that the "pirates" are living in poverty, taking the only paying job available to the them. The real money is made by the warlords and tribal elders who own the boats. The pirates who actually board the ships are working for minimum wage.

Captain Phillips is brutally effective and efficient in telling its story, but it lacks a certain humanity that would have made it really memorable. It's telling that the most human and intense moment in the film comes at the very end, shortly after Phillips has been rescued. He's being examined by a Navy doctor and as he tries to answer the doctor's questions he suffers a nervous breakdown. It's not a showy or hammy piece of acting by Hanks, but it's stone cold brilliant, and if they awarded acting Oscars for two minute film segments he'd have it nailed. It's also the one scene in the film that will probably linger in your memory.

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Book Review: Attack of the Theocrats! (2012) by Sean Faircloth

You don't have to look very hard to find juicy targets if you set out to savage the excesses and idiocies of the religious right in America, and Sean Faircloth certainly takes some hefty swings at some low-hanging fruit. Not that there's anything wrong with that. Egregious religious hucksters like Joel Osteen need to be bashed every day of the week and twice on Sundays. Fortunately this book isn't just a roll call of crimes and misdemeanors perpetrated by God botherers, as the English like to call them. Faircloth, a former member of the Maine legislature, also wants to make his book a call to arms against the very real constitutional and legal crimes committed in the name of religiosity, as well setting out some policy ideas on how secular Americans who value the constitutional requirement for the separation of Church and State can take back their country from the likes of Pat Robertson and his (overwhelmingly) GOP allies.

One very important point that Faircloth brings up is that religion in America, at least the kind that inhabits megachurches and shouts from TV screens, is a business. Thanks to a wide variety of tax breaks and subsidies that are intrinsically unconstitutional, people who once upon a time would have been selling lightning rods or baldness cures on street corners are now in the religion business. Religion can be very, very profitable in America. And like any other industry it strives to stay profitable by putting pressure on politicians to grant them favours. In this regard fundamentalist preachers and organizations are no different from pressure groups like the NRA. In relation to this, Faircloth points out that the majority of Americans (according to various polls) would prefer a more secular country and a reining in of the influence held by the religious right. Like the NRA, fundamentalists are the tail wagging the Washington dog thanks to their money, willpower and organizational ability.

This is a slim book, and there isn't a lot of new information here for readers who've paid even minimal attention to this issue over the last couple of decades. It is, however, valuable for two reasons. The first is that Faircloth provides a tidy and trenchant guide to the secular ambitions of America's founding fathers. If you know someone who likes to declare that the founding fathers were devout Christians and wished to create a Christian country, just have them read chapter two of this book and they should shut up pretty quick. The second valuable lesson that comes from this book is that it shows how hard it is for Americans to escape from the tar pit of their own myth-making. And surprisingly, it's Faircloth who's stuck in the tar pit.

Here are two Faircloth quotes from the book:

"American is still the greatest nation on earth because of its commitment to equal treatment under the law, its protection of minority rights, and its separation of Church and State under the Constitution."

And...

"America is the greatest nation on earth--because of our constitutional ideals and founding principles."

The problem here is that Faircloth is using the same language, expressing the same vision, as every oily preacher and teary-eyed Tea Party congressman. They may disagree on what constitutes greatness, but they all agree that America is number one with a bullet. This is lazy, jingoistic thinking. Faircloth's definition of greatness is based on a set of laws and legal principles, which is fine except that a large number of other democracies can easily claim that they have similar or identical laws. And the actual enforcement of those laws should be the barometer of "greatness" not the fact that they're on the books. Declaring on any and all occasions that America is the greatest nation on earth sometimes seems to be the right and duty of every politician, pundit and Joe Citizen of the U.S. of A. no matter what their political stripe. It's a dangerous thing when people, especially politicians, say that they're inhabiting the greatest nation. It's normally the case that countries that are overly fond of declaring global supremacy are either delusional (North Korea) or employ armies of flinty-eyed men in trenchcoats who make sure the citizenry is nodding vigorously in agreement (the former U.S.S.R.). And the word "greatest" implies that a kind of perfection has been achieved. Why change anything or tolerate dissent when you're the greatest? No nation is the greatest. Well, Norway probably is according to all those U.N. health and happiness surveys that come out every year, but I don't think I could put up with those long winter nights and tacky troll dolls everywhere. The point is that throwing around the "greatest" tag when referring to nations is usually a sign of the worst kind of nationalism.

The "greatest nation" trope in American culture and politics is also what might be the chief prayer in what I'm going to call the Church of America. I'd argue that what's known as the religious right is actually a new, hybrid religion that's composed of equal parts capitalist boosterism, white ancestor worship, rabid nationalism, militarism, and a patina of Christianity. As Faircloth accurately points out, the religious right rarely behaves in a Christian fashion. They, unlike Christ, have an actual dislike for the weak, the meek and the poor, and they're definitely not peacemakers. As Faircloth says, the religious right has taken bits and pieces from the Old and New Testament to craft a religious outlook that ennobles capitalism, praises warriors and denigrates scientific thought. The best evidence for this hybridization is the so-called "Prosperity Gospel" which basically turns God into the Uncle Money Bags character from the game of Monopoly. Play the faith game the right way, says the Prosperity Gospel, and you'll be rewarded with riches.

Faircloth thinks he's simply fighting theocrats, but the Church of America is a more complex beast. Arguing the fine points of scripture with C of A worshipers is only part of the battle. The C of A worships America as an abstract concept. Their America is a holy place created by and for white people in which a love of both capitalism and anti-intellectualism are as important as the love of Christ. This blend of religion and nationalism has happened before in places like Russia and Spain, but in those cases organized religion played a central role. In the US, the C of A is a big tent under which groups like the NRA, fundamentalists, libertarians, birthers, white supremacists, and creationists take shelter. All these groups see America as a quasi-religious entity, and so any criticism of America, from whatever angle or with whatever intent, is perceived by them as an act of blasphemy. So when Faircloth advocates pushing back against the theocrats, I don't think he quite realizes the size and character of the hydra he's up against. Any attack on a single branch of the C of A is seen as an attack on all.

Visual proof of the existence of the Church of America is everywhere in the US. If you've never visited America one of the strangest things to be seen is the omnipresence of the country's flag. It's truly everywhere, from clothing to advertisements to the front porches of houses big and small, and in pin form it's worn on the lapels of rich and poor alike. This fetishization of a flag was and is the norm in totalitarian states, but the US is the only country in which it's been done by popular choice--the land of the free and the brave, and star-spangled, theocratic Don Drapers.

One very important point that Faircloth brings up is that religion in America, at least the kind that inhabits megachurches and shouts from TV screens, is a business. Thanks to a wide variety of tax breaks and subsidies that are intrinsically unconstitutional, people who once upon a time would have been selling lightning rods or baldness cures on street corners are now in the religion business. Religion can be very, very profitable in America. And like any other industry it strives to stay profitable by putting pressure on politicians to grant them favours. In this regard fundamentalist preachers and organizations are no different from pressure groups like the NRA. In relation to this, Faircloth points out that the majority of Americans (according to various polls) would prefer a more secular country and a reining in of the influence held by the religious right. Like the NRA, fundamentalists are the tail wagging the Washington dog thanks to their money, willpower and organizational ability.

This is a slim book, and there isn't a lot of new information here for readers who've paid even minimal attention to this issue over the last couple of decades. It is, however, valuable for two reasons. The first is that Faircloth provides a tidy and trenchant guide to the secular ambitions of America's founding fathers. If you know someone who likes to declare that the founding fathers were devout Christians and wished to create a Christian country, just have them read chapter two of this book and they should shut up pretty quick. The second valuable lesson that comes from this book is that it shows how hard it is for Americans to escape from the tar pit of their own myth-making. And surprisingly, it's Faircloth who's stuck in the tar pit.

Here are two Faircloth quotes from the book:

"American is still the greatest nation on earth because of its commitment to equal treatment under the law, its protection of minority rights, and its separation of Church and State under the Constitution."

And...

"America is the greatest nation on earth--because of our constitutional ideals and founding principles."

The problem here is that Faircloth is using the same language, expressing the same vision, as every oily preacher and teary-eyed Tea Party congressman. They may disagree on what constitutes greatness, but they all agree that America is number one with a bullet. This is lazy, jingoistic thinking. Faircloth's definition of greatness is based on a set of laws and legal principles, which is fine except that a large number of other democracies can easily claim that they have similar or identical laws. And the actual enforcement of those laws should be the barometer of "greatness" not the fact that they're on the books. Declaring on any and all occasions that America is the greatest nation on earth sometimes seems to be the right and duty of every politician, pundit and Joe Citizen of the U.S. of A. no matter what their political stripe. It's a dangerous thing when people, especially politicians, say that they're inhabiting the greatest nation. It's normally the case that countries that are overly fond of declaring global supremacy are either delusional (North Korea) or employ armies of flinty-eyed men in trenchcoats who make sure the citizenry is nodding vigorously in agreement (the former U.S.S.R.). And the word "greatest" implies that a kind of perfection has been achieved. Why change anything or tolerate dissent when you're the greatest? No nation is the greatest. Well, Norway probably is according to all those U.N. health and happiness surveys that come out every year, but I don't think I could put up with those long winter nights and tacky troll dolls everywhere. The point is that throwing around the "greatest" tag when referring to nations is usually a sign of the worst kind of nationalism.

The "greatest nation" trope in American culture and politics is also what might be the chief prayer in what I'm going to call the Church of America. I'd argue that what's known as the religious right is actually a new, hybrid religion that's composed of equal parts capitalist boosterism, white ancestor worship, rabid nationalism, militarism, and a patina of Christianity. As Faircloth accurately points out, the religious right rarely behaves in a Christian fashion. They, unlike Christ, have an actual dislike for the weak, the meek and the poor, and they're definitely not peacemakers. As Faircloth says, the religious right has taken bits and pieces from the Old and New Testament to craft a religious outlook that ennobles capitalism, praises warriors and denigrates scientific thought. The best evidence for this hybridization is the so-called "Prosperity Gospel" which basically turns God into the Uncle Money Bags character from the game of Monopoly. Play the faith game the right way, says the Prosperity Gospel, and you'll be rewarded with riches.

Faircloth thinks he's simply fighting theocrats, but the Church of America is a more complex beast. Arguing the fine points of scripture with C of A worshipers is only part of the battle. The C of A worships America as an abstract concept. Their America is a holy place created by and for white people in which a love of both capitalism and anti-intellectualism are as important as the love of Christ. This blend of religion and nationalism has happened before in places like Russia and Spain, but in those cases organized religion played a central role. In the US, the C of A is a big tent under which groups like the NRA, fundamentalists, libertarians, birthers, white supremacists, and creationists take shelter. All these groups see America as a quasi-religious entity, and so any criticism of America, from whatever angle or with whatever intent, is perceived by them as an act of blasphemy. So when Faircloth advocates pushing back against the theocrats, I don't think he quite realizes the size and character of the hydra he's up against. Any attack on a single branch of the C of A is seen as an attack on all.

Visual proof of the existence of the Church of America is everywhere in the US. If you've never visited America one of the strangest things to be seen is the omnipresence of the country's flag. It's truly everywhere, from clothing to advertisements to the front porches of houses big and small, and in pin form it's worn on the lapels of rich and poor alike. This fetishization of a flag was and is the norm in totalitarian states, but the US is the only country in which it's been done by popular choice--the land of the free and the brave, and star-spangled, theocratic Don Drapers.

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Book Review: A Very Profitable War (1984) by Didier Daeninckx

If, like me, you relish crime fiction that has a political component, then you're resigned to the fact that your choices will be restricted to authors writing in languages other than English, which means the supply of such fiction is limited by what editors and publishers think is worth translating. UK and US crime writers seem gun shy when it comes to politics. They'll sometimes take notice of the symptoms of bad or corrupt political decisions (poverty, urban decay, racism, etc.), but they generally avoid tackling politics head-on. The late Elmore Leornard, for example, set at least a dozen novels in Detroit, a city that has come to symbolize all that is wrong and dysfunctional in American society and politics. But Leonard doesn't have anything to say about the whys and wherefores that turned Detroit into an urban wasteland. He records the symptoms of Detroit's decline but has no apparent opinions on why this has come to pass. The same neutral attitude towards societal ills is a commonplace one with a great many of his English language contemporaries.

Non-Anglo writers such as Massimo Carlotto, Yasmina Khadra, Dominique Manotti and Didier Daeninckx wholeheartedly embrace the political. For them, crime is inextricably linked with political decisions and the political zeitgeist. Their novels reflect the fact that politics and society can have as great a role in fictional murder and mayhem as traditional motives like greed, jealousy and rage. A Very Profitable War is set in Paris in 1920, and our hero is Rene Griffon, a veteran who was recently in the trenches and is now a private eye. He's hired by a retired general who's being blackmailed over his wife's serial indiscretions. What begins as a simple case of marital infidelity turns into a story about war crimes, radical post-WW I politics in Paris, and corporate greed.

The political themes don't make the novel dry or preachy; quite the contrary. Daeninckx's prose style is positively ebullient, full of jokes and energy, and the same can be said about Rene Griffon. As in his Murder in Memoriam (review here), Daeninckx wants to lay bare some of the dirty secrets from France's past. In this case he's concerned with the repression of anarchist and communist movements during and just after the war. These issues add some depth and resonance to the novel, making it more than just an exercise in style and mood. And style and mood is what too many contemporary crime fiction is all about. A great deal of noir or hard-boiled crime fiction works hard to create a gritty, sour, dystopian worldview, but the authors have little interest in explaining why these conditions exist; instead we get a lot of characters (including the sleuths) with deep and dark psychological problems that must be talked about at great length. There's certainly room for both kinds of crime fiction, but it would be nice to see more agitprop writing on the English language side of the ledger. After all, it was Eric Ambler, an English writer, who invented the politically-informed thriller. One American crime writer with a taste for politics is K.C. Constantine (read my piece on him here), although I think he's currently retired from writing. He offers an interesting comparison with Elmore Leonard. Constantine set all his crime novels in a small area of rural Pennsylvania, and he isn't shy about describing the political errors and crimes that have ruined the lives of people in that part of America. Leonard's resolutely apolitical stories stand in stark contrast to Constantine's, although in many ways they are literary blood brothers.

Non-Anglo writers such as Massimo Carlotto, Yasmina Khadra, Dominique Manotti and Didier Daeninckx wholeheartedly embrace the political. For them, crime is inextricably linked with political decisions and the political zeitgeist. Their novels reflect the fact that politics and society can have as great a role in fictional murder and mayhem as traditional motives like greed, jealousy and rage. A Very Profitable War is set in Paris in 1920, and our hero is Rene Griffon, a veteran who was recently in the trenches and is now a private eye. He's hired by a retired general who's being blackmailed over his wife's serial indiscretions. What begins as a simple case of marital infidelity turns into a story about war crimes, radical post-WW I politics in Paris, and corporate greed.

The political themes don't make the novel dry or preachy; quite the contrary. Daeninckx's prose style is positively ebullient, full of jokes and energy, and the same can be said about Rene Griffon. As in his Murder in Memoriam (review here), Daeninckx wants to lay bare some of the dirty secrets from France's past. In this case he's concerned with the repression of anarchist and communist movements during and just after the war. These issues add some depth and resonance to the novel, making it more than just an exercise in style and mood. And style and mood is what too many contemporary crime fiction is all about. A great deal of noir or hard-boiled crime fiction works hard to create a gritty, sour, dystopian worldview, but the authors have little interest in explaining why these conditions exist; instead we get a lot of characters (including the sleuths) with deep and dark psychological problems that must be talked about at great length. There's certainly room for both kinds of crime fiction, but it would be nice to see more agitprop writing on the English language side of the ledger. After all, it was Eric Ambler, an English writer, who invented the politically-informed thriller. One American crime writer with a taste for politics is K.C. Constantine (read my piece on him here), although I think he's currently retired from writing. He offers an interesting comparison with Elmore Leonard. Constantine set all his crime novels in a small area of rural Pennsylvania, and he isn't shy about describing the political errors and crimes that have ruined the lives of people in that part of America. Leonard's resolutely apolitical stories stand in stark contrast to Constantine's, although in many ways they are literary blood brothers.

Monday, October 14, 2013

Film Review: Gravity (2013)

WARNING: MAJOR SPOILERS AHEAD!

I've never been a fan of 3D films, and I've yet to see a film that was improved by its use. Until now. Gravity in 3D looks great and probably gives us earth-dwellers a very real sense of what it's like to float around in space. In fact, at times Gravity feels less like a feature film and more like something you'd see at a science centre planetarium. The film's technical excellence doesn't, however, save it from being a bit ho-hum and downright clunky in some areas.

The film begins with Bullock and Clooney's characters (she's Ryan, he's Matt) floating outside the space shuttle making repairs to the Hubble space telescope. And here's where things get off to a rocky start. If your attention isn't completely diverted by the space scenery you'll notice that Ryan and Matt are having an utterly ridiculous conversation. It's been established that they've been in space a week at this point, which is in addition to whatever training goes on before one of these flights, and yet they talk as though they only met five minutes ago. Matt actually asks her where she's from! The scriptwriter is frantically trying to provide some backstory for the characters in the few minutes available to him before the shit hits the fan but this is a desperately clumsy way to do it. And why was it decided that Matt should be the most cliche astronaut since Buzz Lightyear? He listens to creaky country music as he works; he wisecracks with Mission Control; he's seen it all and done it all in space; he's supernaturally calm under pressure; and he's brave, brave, brave.

The probable reason for Matt's outsized personality is that about twenty minutes into the film he's killed off. He's been setup to be the omni-competent hero who'll figure out how to save the day once the space shuttle is destroyed by a cloud of space debris, so his death (a noble act of self-sacrifice) is intended to act as both a shock and as a way to ratchet up the tension. How will the inexperienced, terrified Ryan manage to save herself? Matt's death actually does a lot of damage to the film. For one thing he's a more engaging personality than Ryan, even if he is a grab bag of heroic cliches. Ryan spends the rest of the film whimpering, shrieking and crying, which gets a bit wearing after a while. She's no Ellen Ripley. The bigger problem is that Matt's death drains a lot of tension out of the film. The film's still got more than an hour to go and since Ryan's the only character, we know she's going to survive until the end. Her struggles and hairbreadth escapes are visually entertaining but they don't produce much tension.

The mechanics of Ryan's journey from a wrecked space shuttle to a successful landing back on Earth are poorly handled. The fact that it's all wildly improbable isn't the problem. What's annoying is that we're not allowed to understand the nuts and bolts of the technical challenges she faces. Scene after scene has Ryan pushing buttons and flipping levers, but it's all meaningless to the audience. Apollo 13, the only film comparable to this one, did a far better job of making us understand the technical challenges faced by astronauts in peril. Gravity succeeds brilliantly as a visual extravaganza, but the storytelling isn't up to the same standards.

I've never been a fan of 3D films, and I've yet to see a film that was improved by its use. Until now. Gravity in 3D looks great and probably gives us earth-dwellers a very real sense of what it's like to float around in space. In fact, at times Gravity feels less like a feature film and more like something you'd see at a science centre planetarium. The film's technical excellence doesn't, however, save it from being a bit ho-hum and downright clunky in some areas.

The film begins with Bullock and Clooney's characters (she's Ryan, he's Matt) floating outside the space shuttle making repairs to the Hubble space telescope. And here's where things get off to a rocky start. If your attention isn't completely diverted by the space scenery you'll notice that Ryan and Matt are having an utterly ridiculous conversation. It's been established that they've been in space a week at this point, which is in addition to whatever training goes on before one of these flights, and yet they talk as though they only met five minutes ago. Matt actually asks her where she's from! The scriptwriter is frantically trying to provide some backstory for the characters in the few minutes available to him before the shit hits the fan but this is a desperately clumsy way to do it. And why was it decided that Matt should be the most cliche astronaut since Buzz Lightyear? He listens to creaky country music as he works; he wisecracks with Mission Control; he's seen it all and done it all in space; he's supernaturally calm under pressure; and he's brave, brave, brave.

The probable reason for Matt's outsized personality is that about twenty minutes into the film he's killed off. He's been setup to be the omni-competent hero who'll figure out how to save the day once the space shuttle is destroyed by a cloud of space debris, so his death (a noble act of self-sacrifice) is intended to act as both a shock and as a way to ratchet up the tension. How will the inexperienced, terrified Ryan manage to save herself? Matt's death actually does a lot of damage to the film. For one thing he's a more engaging personality than Ryan, even if he is a grab bag of heroic cliches. Ryan spends the rest of the film whimpering, shrieking and crying, which gets a bit wearing after a while. She's no Ellen Ripley. The bigger problem is that Matt's death drains a lot of tension out of the film. The film's still got more than an hour to go and since Ryan's the only character, we know she's going to survive until the end. Her struggles and hairbreadth escapes are visually entertaining but they don't produce much tension.

The mechanics of Ryan's journey from a wrecked space shuttle to a successful landing back on Earth are poorly handled. The fact that it's all wildly improbable isn't the problem. What's annoying is that we're not allowed to understand the nuts and bolts of the technical challenges she faces. Scene after scene has Ryan pushing buttons and flipping levers, but it's all meaningless to the audience. Apollo 13, the only film comparable to this one, did a far better job of making us understand the technical challenges faced by astronauts in peril. Gravity succeeds brilliantly as a visual extravaganza, but the storytelling isn't up to the same standards.

Saturday, October 12, 2013

Finally, Proof that Jesus Would Vote Republican

I'm reposting this blog from February, 2012, because it offers one explanation for why the Tea Party/knuckle-dragging segment of the GOP is willing send the U.S. into a depression rather than see the Affordable Care Act receive funding.

As the rough beast of American presidential politics begins its long slouch towards decision day in November, the civilized world is left wondering, as it does every four years, WTF is up with America's obsession with religion? In just last the few days President Obama has had to come up with a compromise on the birth control portion of his health care package in order to placate the Catholic Church, and this is against the backdrop of the Republican primaries, which consist entirely of white multimillionaires trying to proclaim that not only are they more god-fearing than the next guy, but they'll actually make America more god-fearing if given the chance in November. Once the actual presidential campaign begins the two candidates will invoke or quote Jesus and his dad in virtually every speech, and on Sundays we'll see them drop in on the nearest suburban megachurch where their piety will be on full display. But that won't stop both candidates from inferring, or even declaring, that their opponent is in some way heretical or godless.

The auto-da-fé of the American presidential election is a wonderment to Canadians and Europeans because it's a reminder that Yanks are more religious, by far, than anyone else on the block. But why is this? A few months ago I was researching this issue for an article and I kept looking for cultural and political causes of America's religiosity. Nothing seemed to explain the situation until I thought of the other major difference between Europe and the US: social welfare spending. Europe believes in it, America (its ruling class, at least) loathes it. So I Googled social welfare spending and religion and came up with this academic paper written by Anthony Gill (his website's here)and Erik Lundsgaarde, professors at the University of Washington. Eureka! Solid evidence to explain the religiosity divide between America and most everyone else. Before I go further here are some quotes from the paper:

"...state welfare spending has a detrimental, albeit unintended, effect on long-term religious participation and overall religiosity."

"People living in countries with high social welfare spending per capita even have less of a tendency to take comfort in religion, perhaps knowing that the state is there to help them in times of crisis."

The professors back up these conclusions with all the necessary facts and figures (graph alert!), and their paper makes for very interesting reading, but be warned that it is an academic paper so it's a tad on the dry side. The profs argue that as church-sponsored social welfare programs (education, relief for the poor, etc.) are replaced by state programs, people see less value in religion itself. Religiosity (it's defined as weekly church attendance in the paper) does not, however, decline immediately upon an increase in social welfare spending. Decreases in religiosity are generational.

The paper emphasizes the role of churches in providing social welfare support as one of the key causes of religiosity. That's where I disagree with them. I don't think American churches have any significant tradition of providing material support for their followers. I think a more likely explanation, which is hinted at in several places in the paper, is that fear is what drives some people to church, and since WW II the US has been one of the most fear-filled countries on the planet. First there was the Cold War and its fear of nuclear war, then the Vietnam War, fear of street crime in the 1970s, and then a reboot of the Cold War under Ronald Reagan. Add in the wars in the Middle East and 9/11 and you have society that's filled with dread. It's small wonder that Americans look for supernatural protection and comfort when so much that surrounds them seems so dangerous and unpredictable. And this is all on top of a society that provides the most meagre of social safety nets.

It doesn't come as much of a surprise that the Scandinavian countries, with their broad and comprehensive social welfare programs and non-involvement in military conflicts, sit at the bottom of the league in terms of religiosity. It's a clear message that people who have some confidence in their future well-being, who don't live in fear of death and disaster lurking around the next corner, have no need of imaginary beings to protect them. Needless to say there are probably a dozen other factors that can help account for US religiosity, but it would seem that free, universal health care goes a long way towards creating and maintaining a secular society. Gill and Lundsgaarde's paper provides some more proof of this with the example of the ex-Soviet Union. Once religion was made legal in Russia after the fall of the USSR, spirituality made a big comeback. It was no coincidence that the end of the USSR also marked the end of cradle-to-grave welfare programs for Russians, not to mention the end of a guaranteed job for all.

The role of religion in American politics became a big deal in the 1970s as President Jimmy Carter let it be known that he was a "born again" Christian. That seemed to be the starting bell for the evangelical movement, and it's become a key factor in every presidential election since. The rise of the Christian right has gone in lockstep with the erosion of social welfare programs that began with the election of Reagan in 1980. The US is now at a point where the Tea Party and the various Republican presidential hopefuls spend enormous effort in thinking of ways the US government can do less for its people, except, of course, when it comes to waging wars. All this looks like more evidence of religiosity being largely dependent on social welfare spending.

So, from the point of view of a ruthless, evangelical Republican politician there could be no shrewder political strategy than to cut any and all social welfare programs; its appears to be a guaranteed way to fill the pews and stuff the ballot boxes with votes for the GOP. And, really, it's probably what Jesus would do. He wouldn't want a nation of happy, healthy unbelievers. Of course, there was that time he fed the multitudes with free bread and fish...that does sound a bit welfare-ish, a bit food stamp-y, but it was probably a deliberate mistranslation by some liberal, elitist professor of ancient languages.

As the rough beast of American presidential politics begins its long slouch towards decision day in November, the civilized world is left wondering, as it does every four years, WTF is up with America's obsession with religion? In just last the few days President Obama has had to come up with a compromise on the birth control portion of his health care package in order to placate the Catholic Church, and this is against the backdrop of the Republican primaries, which consist entirely of white multimillionaires trying to proclaim that not only are they more god-fearing than the next guy, but they'll actually make America more god-fearing if given the chance in November. Once the actual presidential campaign begins the two candidates will invoke or quote Jesus and his dad in virtually every speech, and on Sundays we'll see them drop in on the nearest suburban megachurch where their piety will be on full display. But that won't stop both candidates from inferring, or even declaring, that their opponent is in some way heretical or godless.

The auto-da-fé of the American presidential election is a wonderment to Canadians and Europeans because it's a reminder that Yanks are more religious, by far, than anyone else on the block. But why is this? A few months ago I was researching this issue for an article and I kept looking for cultural and political causes of America's religiosity. Nothing seemed to explain the situation until I thought of the other major difference between Europe and the US: social welfare spending. Europe believes in it, America (its ruling class, at least) loathes it. So I Googled social welfare spending and religion and came up with this academic paper written by Anthony Gill (his website's here)and Erik Lundsgaarde, professors at the University of Washington. Eureka! Solid evidence to explain the religiosity divide between America and most everyone else. Before I go further here are some quotes from the paper:

"...state welfare spending has a detrimental, albeit unintended, effect on long-term religious participation and overall religiosity."

"People living in countries with high social welfare spending per capita even have less of a tendency to take comfort in religion, perhaps knowing that the state is there to help them in times of crisis."

The professors back up these conclusions with all the necessary facts and figures (graph alert!), and their paper makes for very interesting reading, but be warned that it is an academic paper so it's a tad on the dry side. The profs argue that as church-sponsored social welfare programs (education, relief for the poor, etc.) are replaced by state programs, people see less value in religion itself. Religiosity (it's defined as weekly church attendance in the paper) does not, however, decline immediately upon an increase in social welfare spending. Decreases in religiosity are generational.

The paper emphasizes the role of churches in providing social welfare support as one of the key causes of religiosity. That's where I disagree with them. I don't think American churches have any significant tradition of providing material support for their followers. I think a more likely explanation, which is hinted at in several places in the paper, is that fear is what drives some people to church, and since WW II the US has been one of the most fear-filled countries on the planet. First there was the Cold War and its fear of nuclear war, then the Vietnam War, fear of street crime in the 1970s, and then a reboot of the Cold War under Ronald Reagan. Add in the wars in the Middle East and 9/11 and you have society that's filled with dread. It's small wonder that Americans look for supernatural protection and comfort when so much that surrounds them seems so dangerous and unpredictable. And this is all on top of a society that provides the most meagre of social safety nets.

It doesn't come as much of a surprise that the Scandinavian countries, with their broad and comprehensive social welfare programs and non-involvement in military conflicts, sit at the bottom of the league in terms of religiosity. It's a clear message that people who have some confidence in their future well-being, who don't live in fear of death and disaster lurking around the next corner, have no need of imaginary beings to protect them. Needless to say there are probably a dozen other factors that can help account for US religiosity, but it would seem that free, universal health care goes a long way towards creating and maintaining a secular society. Gill and Lundsgaarde's paper provides some more proof of this with the example of the ex-Soviet Union. Once religion was made legal in Russia after the fall of the USSR, spirituality made a big comeback. It was no coincidence that the end of the USSR also marked the end of cradle-to-grave welfare programs for Russians, not to mention the end of a guaranteed job for all.

The role of religion in American politics became a big deal in the 1970s as President Jimmy Carter let it be known that he was a "born again" Christian. That seemed to be the starting bell for the evangelical movement, and it's become a key factor in every presidential election since. The rise of the Christian right has gone in lockstep with the erosion of social welfare programs that began with the election of Reagan in 1980. The US is now at a point where the Tea Party and the various Republican presidential hopefuls spend enormous effort in thinking of ways the US government can do less for its people, except, of course, when it comes to waging wars. All this looks like more evidence of religiosity being largely dependent on social welfare spending.

So, from the point of view of a ruthless, evangelical Republican politician there could be no shrewder political strategy than to cut any and all social welfare programs; its appears to be a guaranteed way to fill the pews and stuff the ballot boxes with votes for the GOP. And, really, it's probably what Jesus would do. He wouldn't want a nation of happy, healthy unbelievers. Of course, there was that time he fed the multitudes with free bread and fish...that does sound a bit welfare-ish, a bit food stamp-y, but it was probably a deliberate mistranslation by some liberal, elitist professor of ancient languages.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Film Review: Unit 7 (2012)

If there's a film genre that's deader than the western it's cop films. Cop dramas are alive and well on TV; in fact, it's probably the case that the glut of cop shows on TV kills any appetite the public has for seeing them in the cinema. The plethora of TV westerns in the 1960s is often cited as the reason for the extinction of the genre, so we're probably seeing the same process at work with cop films. By cop films I don't mean buddy cop films like the Lethal Weapon franchise or the Die Hard films, which are essentially blue collar James Bond adventures. When I say cop films I'm referring to the cop noir genre (my own description; more details here) that emerged in the '70s with The French Connection. Cop films of that era were grittty, realistic and were thematically linked by their examination of the rotten heart of big cities. To put it in a nutshell, cop noir films took an unrelentingly dystopian look at urban life.

Good news! Some cop noir films are still being made and Group 7 is one of the better ones I've seen. The title refers to a four-man squad of cops tasked with cleaning up the drug business in Seville, Spain, in 1988. The civic authorities want the crackdown because Seville is hosting the World's Fair in 1992 and they're keen to present a clean and shiny face to the world. Our heroes take to the job with gusto, cracking heads, leaning on informants, and generally making a name for themselves as they put a big dent in the local drugs trade. Along the way, however, they decide that they should take a taste of the business themselves. They install an ex-madam in an apartment block and make her their tame drug dealer. After two years Group 7 has become locally famous and is hated by both other cops and members of the criminal underworld. Internal Affairs gets after them, as do some local criminals.

Group 7 has the look and feel of cop noir down pat, but what makes it pleasurably different is that it doesn't end in any of the expected ways. There is a shootout towards the end, and some scary moments for individual members of the group, but there's no attempt to tie up loose ends. The film ends with the cops going off in different career directions, and we're left with is the realization that the local war on drugs has been utterly pointless and futile; nothing more than a PR exercise that's taken a fearful toll. The more things change...

Good news! Some cop noir films are still being made and Group 7 is one of the better ones I've seen. The title refers to a four-man squad of cops tasked with cleaning up the drug business in Seville, Spain, in 1988. The civic authorities want the crackdown because Seville is hosting the World's Fair in 1992 and they're keen to present a clean and shiny face to the world. Our heroes take to the job with gusto, cracking heads, leaning on informants, and generally making a name for themselves as they put a big dent in the local drugs trade. Along the way, however, they decide that they should take a taste of the business themselves. They install an ex-madam in an apartment block and make her their tame drug dealer. After two years Group 7 has become locally famous and is hated by both other cops and members of the criminal underworld. Internal Affairs gets after them, as do some local criminals.

Group 7 has the look and feel of cop noir down pat, but what makes it pleasurably different is that it doesn't end in any of the expected ways. There is a shootout towards the end, and some scary moments for individual members of the group, but there's no attempt to tie up loose ends. The film ends with the cops going off in different career directions, and we're left with is the realization that the local war on drugs has been utterly pointless and futile; nothing more than a PR exercise that's taken a fearful toll. The more things change...

Saturday, October 5, 2013

Book Review: Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959) by Paule Marshall

The central character in Brownstones is Selina, one of two daughters of Sella and Deighton Boyce. The family, like most of their fellow Bajans, are struggling to get by. The Bajans take menial jobs as cleaners and domestics, and every family's dream is to buy one of Brooklyn's large, iconic brownstone row houses and rent it out its rooms to the next wave of immigrants. The difference with the Boyce family is that Deighton is a professional ne'er do well. While Sella works all the hours of the day, Deighton lounges at home, takes the ocassional job, and visits his mistress. Needless to say, Sella and Deighton have a fraught relationship. Sella is the polar opposite. She is consumed with a desire to get ahead, to own a piece of property and then become a landlord, preferably in the more middle-class environs of Crown Heights. Sella's ambition and drive turn her into a kind of monster to her children, especially Selina, who worships her father. As Selina enters adulthood and goes to college she begins to feel torn between the expectations of her mother and the Bajan community, and her own desires to be part of a larger world.

Brownstones features some sharp, evocative writing, especially in its portrait of Brooklyn from an immigrant's point of view. What makes it special is that these are black characters seen without looking through the usual prism of white society or white characters. Towards the end of the novel Selina makes an uncomfortable acquaintance with the larger white world, but the majority of the novel is a character-focused study of hardscrabble immigrant life and the terrible toll it can take on both family and romantic relationships. Racial issues aren't of primary concern here. The end of the novel loses its way somewhat thanks to some editorializing and an unsatisfying ending, but it's certainly one of the better literary studies of immigrant life that I've come across.

Friday, October 4, 2013

Closed to the Public, Open for a Coup

What's really scary about the current debt ceiling crisis in the US isn't the prospect of a recession/depression if the US defaults on its loans, it's that what we're seeing is the endgame in a concerted effort by Republicans and their various backers, from middle-class white God-botherers in the South to the Koch brothers in New York, to finally "break" the federal government, to reduce it to an organization with only two purposes: to maintain a strong, belligerent military and to facilitate the growth of corporate profits. And worse still, this goal will be achieved after a "soft" coup that will formally end America's fragile status as a democracy.

The economic chaos that would result from a default is exactly what the far right of the Republican Party wants. Why, you ask? In chaos lies opportunity. Democracies that fall into crisis almost inevitably see a shift in political power at the next election. The party or president or prime minister in power when the crisis arises or reaches the boiling point invariably gets the blame for the situation (rightly or wrongly) and is turfed. The Republicans are engineering such a crisis with an eye on the 2016 elections. If a default occurs the GOP will go into the next election labeling it "The Democrat default" in the same way they disparagingly labelled the Affordable Care Act as Obamacare. Whoever has the thankless job of running for the Democrats in 2016 will go down in flames, and a Republican will move into the White House.

This is when the coup will take place. The corrosive, anti-democratic course of US politics will be strengthened and the way paved for permanent Republican rule. How? Congressional districts will be gerrymandered even more than they are now; further tightening of voter registration laws will take the vote away from minorities and the poor; and corporations, already the de facto fourth branch of government thanks to the Citizens United v. FEC ruling, will be granted greater powers to fund and influence election campaigns. I call this a soft coup because there will be no riots, no tanks on the White House lawn, just the quiet shuffling of papers as laws are passed that turn America into a Republican-run, theocratic kleptocracy.The rationale the Republicans will give for their draconian laws and regulations is that the "old" way of governing is broken--the debt crisis proves that a new order is needed in American politics so that nothing like that happens again. And here's where I may run afoul of Godwin's Law, but I'll go ahead and say that a fiscal default in the US could prove to be the American equivalent of the Reichstag fire.

Are Republicans crazy enough to push the US into a full blown recession? Based on the visceral loathing large elements of the Republican Party have for Obama, government, liberals, minorities, the Democrats, and the media (excluding Fox News) it's certain that they've reached the right emotional temperature for radical action. And a non-fiscal issue may be what pushes them over the edge. Obama's tentative steps towards a rapprochement with Iran hits all kinds of right-wing panic buttons. Rightist think tanks, political commentators, and members of Congress are unanimous in their hatred and distrust of Iran. And just this past week Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel's prime minister, gave a speech at the U.N. in which he bluntly told the world, but more specifically the US, that Israel wants no part of negotiations with Iran. It's no secret that Netanyahu can't stand Obama, and it's equally true that Israel has the ear (and several other body parts) of the Republican Party, especially its more evangelical members. It might serve Israel's foreign policy interests to have Obama distracted and weakened by a full-blown economic crisis, and if Israel sees it that way I don't doubt they'll drop a word in the right places in Washington.

It's also entirely possible that the Republicans will end up the losers in this fight, reduced to looking like a pack of cranks and fiscal Luddites who will be savaged in the next election. That's a plausible outcome but even if it does come to pass the anti-democratic elements in the GOP won't be going away any time soon, and if they do lose this fight they'll simply bide their time until the next opportunity arises to throw a spanner in the works.

The economic chaos that would result from a default is exactly what the far right of the Republican Party wants. Why, you ask? In chaos lies opportunity. Democracies that fall into crisis almost inevitably see a shift in political power at the next election. The party or president or prime minister in power when the crisis arises or reaches the boiling point invariably gets the blame for the situation (rightly or wrongly) and is turfed. The Republicans are engineering such a crisis with an eye on the 2016 elections. If a default occurs the GOP will go into the next election labeling it "The Democrat default" in the same way they disparagingly labelled the Affordable Care Act as Obamacare. Whoever has the thankless job of running for the Democrats in 2016 will go down in flames, and a Republican will move into the White House.

This is when the coup will take place. The corrosive, anti-democratic course of US politics will be strengthened and the way paved for permanent Republican rule. How? Congressional districts will be gerrymandered even more than they are now; further tightening of voter registration laws will take the vote away from minorities and the poor; and corporations, already the de facto fourth branch of government thanks to the Citizens United v. FEC ruling, will be granted greater powers to fund and influence election campaigns. I call this a soft coup because there will be no riots, no tanks on the White House lawn, just the quiet shuffling of papers as laws are passed that turn America into a Republican-run, theocratic kleptocracy.The rationale the Republicans will give for their draconian laws and regulations is that the "old" way of governing is broken--the debt crisis proves that a new order is needed in American politics so that nothing like that happens again. And here's where I may run afoul of Godwin's Law, but I'll go ahead and say that a fiscal default in the US could prove to be the American equivalent of the Reichstag fire.

Are Republicans crazy enough to push the US into a full blown recession? Based on the visceral loathing large elements of the Republican Party have for Obama, government, liberals, minorities, the Democrats, and the media (excluding Fox News) it's certain that they've reached the right emotional temperature for radical action. And a non-fiscal issue may be what pushes them over the edge. Obama's tentative steps towards a rapprochement with Iran hits all kinds of right-wing panic buttons. Rightist think tanks, political commentators, and members of Congress are unanimous in their hatred and distrust of Iran. And just this past week Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel's prime minister, gave a speech at the U.N. in which he bluntly told the world, but more specifically the US, that Israel wants no part of negotiations with Iran. It's no secret that Netanyahu can't stand Obama, and it's equally true that Israel has the ear (and several other body parts) of the Republican Party, especially its more evangelical members. It might serve Israel's foreign policy interests to have Obama distracted and weakened by a full-blown economic crisis, and if Israel sees it that way I don't doubt they'll drop a word in the right places in Washington.

It's also entirely possible that the Republicans will end up the losers in this fight, reduced to looking like a pack of cranks and fiscal Luddites who will be savaged in the next election. That's a plausible outcome but even if it does come to pass the anti-democratic elements in the GOP won't be going away any time soon, and if they do lose this fight they'll simply bide their time until the next opportunity arises to throw a spanner in the works.

Tuesday, October 1, 2013

Book Review: The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East (2005) by Robert Fisk

It takes a strong stomach to read this massive history of the Middle East from the Iran-Iraq war up to the second invasion of Iraq in 2003, and not just because it's filled with graphic descriptions of the atrocities inflicted on millions of people with weapons as various as knives, cluster bombs and poison gas. What's really stomach churning is the litany of stupid, racist, cynical and plain old murderous political decisions that have turned the Middle East into a perpetual battleground of competing ideologies, religions, sects and dictators.

Fisk takes a scattershot approach to his history of the region, jumping backwards and forwards in time to chronicle the wars and conflicts in Algeria and Aghanistan and everywhere in-between. This non-chronological approach has drawn disapproving frowns from some critics, but this structure is, I think, intended to reflect Fisk's career as a journalist; always leapfrogging from one bloody crisis to another in the Middle East and North Africa. Also, this is primarily a work of journalism rather than a historical document, although Fisk certainly provides all the needed historical background to the various conflicts he's covered. And his history of the Armenian Genocide strikes a perfect balance between brevity and telling details.

There are several themes that Fisk returns to throughout the book, chief amongst them is the fact that the modern Middle East is largely the creation of the West, and therein lies the root of many of its problems. Today's national borders in the region reflect decisions made by colonial powers in 1919, and despotic regimes in Iraq and Iran were, at various times, installed or approved of by the US and the UK, the chief power brokers in the area after WW II. And of course the most contentious Western creation is Israel, which was essentially imposed on a politically helpless Palestine. But more about Israel later. It's almost a given that frictions and conflicts in the region have their basis in reckless or ignorant decisions made in Washington or various European capitals.

In relation to the above point, Fisk makes it clear that the West has shown a remarkable ability to befriend any and all dictators who are willing to side with Western interests. Saddam Hussein is the poster boy for this Machiavellian strategy. Once the Shah of Iran was deposed from his throne and his role of favoured regional "strongman," Hussein became the new strongman in town and was toasted and feted in world capitals of all political stripes. He tortured and gassed his own people and started a war with Iran? No problem, as long as he's got oil to sell and arms to buy, and as a bonus he's eager to kill lots and lots of Iranians by any means available. This diplomatic formula has been repeated with a score of dictators in the region, which has simply led to a hardening of anti-Western attitudes in the general population. The average citizen of the Middle East can see very well who's propping up or applauding his local despot so it should come as no surprise that Islamist and nationalsit parties (the political groups most likely to be loathed in the West) are able to attract support in the region.

Fisk's book also makes it clear, even if he doesn't say so directly, that the Middle East is, perhaps, ungovernable in the sense that we in the West think of "good" governance. The region is so riven with religious, ethnic and sectarian conflicts, not to mention sub-layers of conflicting tribe and clan loyalties, that it's hard to see how stable government can exist for any length of time, particularly when so many of the societies are nursing toxic fears and grudges leftover sfrom recent wars. Even Israel, which is reflexively offered up as model of statehood in a sea of corrupt and dictatorial regimes, is beginning to fracture along ultra Orthodox and secular lines. As bad as the recent past has been for the Middle East, the future, it seems, could be even worse.

Speaking of Israel, Fisk misses no opportunity to record Israel's crimes and misdemeanors within and without its borders and its tail-wagging-the-dog relationship with the US. His harsh criticisms of Israel have, predictably, caused him to be branded both an anti-semite and an enemy of America. The fact that Fisk's criticisms are no different than those voiced by Israel's homegrown critics (see Ilan Pappe's book on the ethic cleansing of Palestine here) is ignored by Fisk-bashers. Fisk eloquently and relentlessly makes the point that Israel's policy of displacement, colonization and persecution of its Palestinian citizens is glossed over in the West, and its war crimes are held to a different standard than those committed by Palestinian groups. More dangerously, Israel's iron hold on US decision-making in the region has hopelessly compromised any diplomatic initiatives the US undertakes.

The book's defects can be boiled down to two issues: the first is that Fisk's tone is sometimes too hectoring, too much the sarcastic Old Testament prophet. The other problem is that Fisk picks some cheap and easy targets for his wrath. Is anyone surprised that arms merchants don't give a toss about what happens to their deadly merchandise once it goes out the factory door? Apparently Fisk is, and so two sections on the so-called merchants of death end up feeling rather pointless. Other than those issues, this is, as they say, essential reading for any understanding of what has made the Middle East the cockpit of the world.

Fisk takes a scattershot approach to his history of the region, jumping backwards and forwards in time to chronicle the wars and conflicts in Algeria and Aghanistan and everywhere in-between. This non-chronological approach has drawn disapproving frowns from some critics, but this structure is, I think, intended to reflect Fisk's career as a journalist; always leapfrogging from one bloody crisis to another in the Middle East and North Africa. Also, this is primarily a work of journalism rather than a historical document, although Fisk certainly provides all the needed historical background to the various conflicts he's covered. And his history of the Armenian Genocide strikes a perfect balance between brevity and telling details.

There are several themes that Fisk returns to throughout the book, chief amongst them is the fact that the modern Middle East is largely the creation of the West, and therein lies the root of many of its problems. Today's national borders in the region reflect decisions made by colonial powers in 1919, and despotic regimes in Iraq and Iran were, at various times, installed or approved of by the US and the UK, the chief power brokers in the area after WW II. And of course the most contentious Western creation is Israel, which was essentially imposed on a politically helpless Palestine. But more about Israel later. It's almost a given that frictions and conflicts in the region have their basis in reckless or ignorant decisions made in Washington or various European capitals.

In relation to the above point, Fisk makes it clear that the West has shown a remarkable ability to befriend any and all dictators who are willing to side with Western interests. Saddam Hussein is the poster boy for this Machiavellian strategy. Once the Shah of Iran was deposed from his throne and his role of favoured regional "strongman," Hussein became the new strongman in town and was toasted and feted in world capitals of all political stripes. He tortured and gassed his own people and started a war with Iran? No problem, as long as he's got oil to sell and arms to buy, and as a bonus he's eager to kill lots and lots of Iranians by any means available. This diplomatic formula has been repeated with a score of dictators in the region, which has simply led to a hardening of anti-Western attitudes in the general population. The average citizen of the Middle East can see very well who's propping up or applauding his local despot so it should come as no surprise that Islamist and nationalsit parties (the political groups most likely to be loathed in the West) are able to attract support in the region.