One blog I like to wander through regularly is www.pulpcurry.com. Andrew Nette's blog deals in crime fiction, but another aspect of it that really draws my attention are the links to the covers of pulp paperback novels from the 1950s, '60s and '70s. The lurid, enticing, and dynamic artwork on these books takes me right back to my youth when I used to loiter in my local W.H. Smith, paralyzed between buying a book that I knew was respectable and good (a John Wyndham, maybe) and something with a cover that spoke directly to my internal organs (a Carter Brown, certainly). Andrew just posted some covers from novels set in prisons, and while I've never read a prison novel, I realized that of all the prison movies I've seen over the years not one of them has been a dud. In fact, this genre as a whole has a remarkably high success rate. Whether the subject of the film is life in prison or an escape, it seems to be a reasonably foolproof genre for writers and directors. I'm not sure why, but I'd guess that a prison-set story requires stripping away a lot of the extraneous story and character buildup that other genres tolerate. To paraphrase Samuel Johnson: Prison scripts concentrate the writer's mind wonderfully. And so here's my personal top ten prison movies:

The Hill (1965)

The setting is a British military prison in North Africa during WW II, and the subject is the corruption of authority. Sean Connery gives his best performance as a persecuted prisoner, and the cast is filled out by a who's who of Brit actors bellowing their lines as though trying to be heard back in the UK. Special mention to Harry Andrews in the shoutiest role of his long and shouty career.

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

Yet another anti-authority story, this time set on a Florida chain gang. It's slick, it's funny, it's tense, and every scene in the film is designed to highlight Paul Newman's star power and that's OK with me.

Le Trou (1960)

This is a true story of an attempted escape from a Paris prison in 1947. It's told in a documentary style and there's no attempt to glamorize the five prisoners planning the escape; we simply start rooting for them because they're so damned clever and determined.

Papillon (1973)

Sometimes this film feels as long as Henri Charriere's actual prison sentence on Devil's Island, but you can't beat its Hollywood epic quality and the charisma of Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman.

Penitentiary (1979)

The blacksploitation genre was dead by the time this no-budget effort came along, but its almost all-black cast, a lot of them non-actors, give this film a rawness that makes it feel like an actual trip behind bars. It's not a conventionally good film, but it certainly holds your attention.

The Longest Yard (1974)

Some genius decided to combine a sports movie with a prison film and this is the goofy classic that resulted. I nearly laughed up a lung when I first saw it, and for my generation of filmgoers it made a stretch behind bars look like a fun option. The definitive Burt Reynolds performance.

Scum (1979)

If The Longest Yard made hard time look like fun time, Scum takes the scared straight approach. It's set in a British prison for juveniles and it's still probably the nastiest, most violent prison film I've ever seen. A young Ray Winstone has a star-making turn as the new boy who climbs the ladder of brutal violence to become the prison's new "Daddy." Show this one to your young son and he'll be afraid to jaywalk.

The Great Escape (1963)

The Bible, Torah and Koran of prison movies. It's nearly three hours long and there isn't a single second of it that feels superfluous. Vastly entertaining, the secret to its success was revealed to me when I showed it years ago to my son. He became addicted to watching it, and I realized that it's appeal comes from showing a bunch of men who are obliged to misbehave; they steal, sneak around, pull pranks, and thumb their noses at all authority figures. They're very naughty boys, and the film speaks to the bad kid inside each of us.

Cell 211 (2009)

A newly-minted prison guard in a Spanish prison gets caught up in a prison riot and has to pass himself off as a prisoner in order to avoid getting the chop. The basic premise is brilliant (and supposedly has been bought for a Hollywood remake), and even if the execution isn't always the equal of the original concept, this is a clever variation on the genre.

Innocence (2004)

Just to shake things up I'm going to call this French film a prison movie. It's set in a very strange school for young girls who are not allowed to leave the walled grounds under any circumstances. It looks great, it's deeply weird, and you'll either love it or hate it. And here's my original review.

Sunday, September 22, 2013

Sunday, September 15, 2013

Book Review: Brenner and God (2009) by Wolf Haas

Judged solely by its plot, this Austrian mystery is a bit of a disaster. The crime at the centre of the story is the kidnapping of a young girl named Helena. Her mother is an abortion doctor and her father is a wealthy land developer. Helena is taken while in the care of Brenner, an ex-cop presently working as the family's chauffeur. The suspects in the kidnapping include an anti-abortion activist and various people associated with Helena's father's business activities. Brenner feels responsible for losing the girl and starts hunting for her, albeit in a shambolic sort of way.

The plot is stuck together with spit and masking tape, and in the end it turns out to be a bit of a shaggy dog story. Thankfully the plot is the least important aspect of the novel. The story is narrated by an unnamed character who is the true star of the book. He might be an old man buttonholing a stranger to tell his story, or, based on a couple of odd lines in the book, he could equally well be a loony sitting in a park telling his tale to a swan. Our narrator is wildly discursive, philosophical, something of a semiotician, humorous, a social commentator, and very, very entertaining.

Any one picking up this book expecting to read a more or less conventional work of crime fiction is going to be deeply disappointed. You'll either accept its wildly eccentric narrative voice and train wreck of a plot or drop the book like a hot coal. My only beef with the novel is that the translator should have provided a few footnotes or even some kind of introduction. A few German words are used without any hint of what they mean, and some background information on some Austrian locations and institutions would be very beneficial.

The plot is stuck together with spit and masking tape, and in the end it turns out to be a bit of a shaggy dog story. Thankfully the plot is the least important aspect of the novel. The story is narrated by an unnamed character who is the true star of the book. He might be an old man buttonholing a stranger to tell his story, or, based on a couple of odd lines in the book, he could equally well be a loony sitting in a park telling his tale to a swan. Our narrator is wildly discursive, philosophical, something of a semiotician, humorous, a social commentator, and very, very entertaining.

Any one picking up this book expecting to read a more or less conventional work of crime fiction is going to be deeply disappointed. You'll either accept its wildly eccentric narrative voice and train wreck of a plot or drop the book like a hot coal. My only beef with the novel is that the translator should have provided a few footnotes or even some kind of introduction. A few German words are used without any hint of what they mean, and some background information on some Austrian locations and institutions would be very beneficial.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Edward Snowden and King Midas' Ears

|

| "God, I hate extended lyre solos," said Midas, instantly regretting his words. |

Apparently even the ancient Greeks realized two things about secrecy: one; that no secret is safe if it's big enough or especially scandalous, and two; someone holding such a secret has an almost pathological need to reveal it. This brings us to the NSA's barber, Edward Snowden. The political, legal and diplomatic repercussions of Snowden's revelations are almost too numerous to mention, but here's a few things that have intrigued me about this carnival of disclosures.

In a recent Guardian article revealing details of how the NSA and the GCHQ (Britain's equivalent to the NSA) have worked to defeat any and all kinds of internet secrecy, it was mentioned in passing that Snowden was one of 850,000 in the US with clearance to view material classified as "top secret." WTF? How could the NSA not have expected to have one or more Snowden's pop out of the woodwork when the population equivalent of a mid-sized city has been given the OK to comb through top secret material? Put together a random group of 850k people, even with some security vetting, and you're bound to get a variety of personality traits inimical to keeping secrets: egoists, glory seekers, idealists, moralists, ethicists, mischief makers, not to mention those who might want to sell secrets. It wasn't a matter of would an Edward Snowden come along, but when. That mind-boggling number also shows how devalued the concept of "top secret" has become in the information age. The volume of information to be combed through is so vast, so fluid, it requires a large army to keep track of it, and all armies have deserters. When you give top secret clearance to that many people it's tantamount to saying that top secret is really only a guideline. And in our information age with its dozens of sleight-of-hand ways to access, store and transmit data, the concept of "secret" is becoming antiquated; and as individuals in this age we both demand and desire access to any and all kinds of information. Our insatiable desire to know everything, and to share that knowledge, is a stake through the heart for the concept of "top secret."

One of the "sensational" reveals from the Snowden files is the the US and UK have spied on their friends and allies. A quelle surprise this isn't. In 1848 Lord Palmerston, Britain's Foreign Secretary, said, "We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow." And in the 1950s John Foster Dulles, the American Secretary of State, paraphrased Palmerston when he said that "The United States of America does not have friends, it has interests." No one should be shocked or appalled that nations spy on their so-called friends; that is all part and parcel of Great Power politics and has been for a very long time. Commentators who profess to be shocked by this news end up sounding like another US Secretary of State, Henry L. Stimson, who sniffilly said on the subject of spying: "Gentlemen don't read other gentlemen's mail."

It should also be no great surprise that the NSA has been working feverishly to get its ears into every corner of the internet. The NSA's guiding philosophy of trying to listen in to anything relating to America's interests was revealed years ago in The Puzzle Palace (1982) by James Bamford. That book didn't divulge any top secret material, but it didn't take much imagination to realize that the NSA would exploit every opportunity to eavesdrop on its friends and enemies. Snowden's revelations have provided copious details on this eavesdropping, but the broader picture was clear more than thirty years ago.

The NSA's public relations counterattack to the anger over its Argus-like surveillance of the internet has taken the position that the NSA is protecting America from terrorist actions. Put another way, they're portraying themselves as honest cops walking the internet beat. What's becoming clearer and more alarming with every new NSA article in the Guardian is that the agency is simply being used, as Palmerston and Dulles would no doubt approve, to advance America's non-security interests. In the last 24 hours it's been revealed that the NSA was spying on a Brazilian oil company and has a special, but one-sided, relationship with Israeli Intelligence. The Supreme Court's decision in 2010 in the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case (opening the door for unlimited political campaigning by big business) turned the US from a flawed, ramshackle democracy into a corporate-run kleptocracy, so it therefore seems possible and probable that the NSA is now also the intelligence wing of the US Chamber of Commerce. If Boeing or Lockheed Martin or Exxon need some information about what their rivals are up to in other parts of the world, why wouldn't they turn to the NSA and ask for some help? After all, they pretty much own the agency already. And why stop there? What are union organizers up to? Is an environmental group about to launch a lawsuit? Are protestors planning another flotilla to take aid to Palestine? It would be foolish to disregard the possibility that corporate America is being given a helping hand by the NSA, and that Israel doesn't use its privileged access to NSA data to keep an eye on protestors.

What's really been exposed by Edward Snowden is that the US, like any Great Power throughout history armed with money and superior technology, is conditioned to advance and defend its interests against all comers, even those regarded as friendly. Unfortunately there's little hope that the NSA will curtail its activities. Those 850,000 people represent a huge and costly commitment to spying, and the money and jobs generated by the NSA and its private contractors means that the electronic eavesdropping "industry" now has tremendous clout in the halls of power. President Eisenhower warned about this situation when he described the "military-industrial complex." It looks like we're now living in the age of the military-industrial-surveillance complex.

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

Book Review: The Big House: A Century in the Life of an American Summer Home (2003) by George Howe Colt

Part memoir, part nostalgia binge, part history of Cape Cod, what makes this book interesting is its study of the habits and attitudes of WASP Americans. Put your hand up if you're a WASP...No one, of course, put their hand up because a WASP would never want to be noticed or singled out. Speaking as a WASP (Canadian division), I'm annoyed with Colt for breaking the unwritten rule (all WASP rules are unwritten) that attention should never be drawn to oneself. We WASPs also like to use words like "oneself."

The titular house was built in 1903 on Cape Cod for the Atkinson family, well-to-do Bostonians whose family tree had very deep and well-connected roots in American history. At the time the house was built, Americans, and the middle and upper classes in Europe, were beginning to see the seaside as a vacation destination. "Sea bathing" was regarded as healthful and fun. It also gave the affluent a chance to show off their wealth by building summer homes. Flashy oligarchs like the Morgans and Vanderbilts buiilt showy piles farther up the coast in Newport, Rhode Island. Wealthy WASP Bostonians colonized Cape Cod, building homes that were built for comfort and large families, but not for show.

As the book begins in 2003 the Big House is up for sale and about pass out of family hands. The house is now owned in common by descendents of the Atkinsons, and the passing years have seen their collective wealth diminish to the point where upkeep and taxes on the house have become onerous. George Howe Colt (WASPs always use their middle names) spent most or part of every summer at the Big House, and a large part of the book is his memoir of the joys and peculiarities of summer life in Cape Cod. This aspect of the book is quite good. Colt is very effective at recreating the magical impact a big, rambling house by the beach has on kids and teens. At times Colt trips over into dewy-eyed sentimentality, but those episodes are, thankfully, few and far between.

Colt's portrait of his Atkinson/Colt ancestors and relatives is fascinating as a field guide to WASP customs and behavior. He pulls no punches when describing the stiff upper lips, the quiet despair, the discreet alcoholism, marriages that crumble behind closed doors, and etiquette and tradition used to tamp down emotions and desires. Yup, that's life as a WASP. But it's not all angst. Colt speaks with justifiable pride about his family's history of public service and commitment to supporting each other through thick and thin. At times his memoir touched pretty closely on my own life as a WASP, although my family tree had a lot less money and never shaded a summer home. As a memoir of summer life in a beautiful part of the US, The Big House is enjoyable, although it has to be kept in mind that this was, and is, a privilege that comes to a very few people. As a look at the beige heart of WASPiness, it's much more intriguing, although Colt will have to answer for his candidness; I insist he report to a council of his elders at the yacht club nearest to him.

The titular house was built in 1903 on Cape Cod for the Atkinson family, well-to-do Bostonians whose family tree had very deep and well-connected roots in American history. At the time the house was built, Americans, and the middle and upper classes in Europe, were beginning to see the seaside as a vacation destination. "Sea bathing" was regarded as healthful and fun. It also gave the affluent a chance to show off their wealth by building summer homes. Flashy oligarchs like the Morgans and Vanderbilts buiilt showy piles farther up the coast in Newport, Rhode Island. Wealthy WASP Bostonians colonized Cape Cod, building homes that were built for comfort and large families, but not for show.

As the book begins in 2003 the Big House is up for sale and about pass out of family hands. The house is now owned in common by descendents of the Atkinsons, and the passing years have seen their collective wealth diminish to the point where upkeep and taxes on the house have become onerous. George Howe Colt (WASPs always use their middle names) spent most or part of every summer at the Big House, and a large part of the book is his memoir of the joys and peculiarities of summer life in Cape Cod. This aspect of the book is quite good. Colt is very effective at recreating the magical impact a big, rambling house by the beach has on kids and teens. At times Colt trips over into dewy-eyed sentimentality, but those episodes are, thankfully, few and far between.

Colt's portrait of his Atkinson/Colt ancestors and relatives is fascinating as a field guide to WASP customs and behavior. He pulls no punches when describing the stiff upper lips, the quiet despair, the discreet alcoholism, marriages that crumble behind closed doors, and etiquette and tradition used to tamp down emotions and desires. Yup, that's life as a WASP. But it's not all angst. Colt speaks with justifiable pride about his family's history of public service and commitment to supporting each other through thick and thin. At times his memoir touched pretty closely on my own life as a WASP, although my family tree had a lot less money and never shaded a summer home. As a memoir of summer life in a beautiful part of the US, The Big House is enjoyable, although it has to be kept in mind that this was, and is, a privilege that comes to a very few people. As a look at the beige heart of WASPiness, it's much more intriguing, although Colt will have to answer for his candidness; I insist he report to a council of his elders at the yacht club nearest to him.

Friday, September 6, 2013

Loving Movies to Bits, Or the Ten Greatest Gesamtkunstwerk Films

|

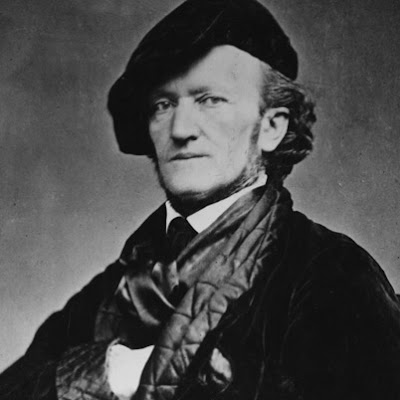

| Richard Wagner: father of gestamkunstwerk & Kangol hats |

What makes film subject to this atomized appreciation is that so there are so many different artistic elements that go into creating even the most basic, B-grade movie. It's really quite wonderful that film production can bring together so many different creative impulses, and, not surprisingly, the Germans have a big, fat word to describe this kind of art: gesamtkunstwerk. Gesamtkunstwerk, according to Wikipedia, describes a work of art that incorporates or uses all or many art forms. Gesamtkunstwerk was evidently a concept that composer Richard Wagner (the Michael Bay of nineteenth-century opera) heartily embraced.

Movies are the ultimate example of gesamtkunstwerk. Nothing else really comes close. From the script to the acting to the props, each element in a film can be used to make a profound impression on an audience's imagination. The Wizard of Oz is a musical but it's almost equally beloved for its set design, and the films of Fellini and Hitchcock are as well known for their soundtracks, courtesy of Nino Rota and Bernard Herrmann, as they are for their visuals. And moving down the artistic pecking order comes Something's Gotta Give (2003), a moderately successful comedy with Diane Keaton and Jack Nicholson. The look and layout of the the home owned by Keaton's character struck a chord with audiences, and soon interior designers across North American were being asked to replicate it in every detail. A single element in a film can have a life outside of the original creation, and the vibrancy of that life will keep audiences coming back to the film to reconnect with it again and again.

Not every great film is an example of gesamtkunstwerk, including some films that are widely, and justly, regarded as classics. Director John Huston, for example, made a lot of great films, but he was not what I'd call a gesamtkunstwerk director. Huston concentrated on story and character to the exclusion of all else. His films were shot in a pedestrian style, the music isn't notable, and he had no distinctive visual style. Huston was, however, a great storyteller. I guess you could say that as a director he was a great novelist. And then there are directors like Kubrick, Fellini, and Hitchcock, none of whom knew how to make a film that wasn't a terrific example of gesamtkunstwerk.

So now here's my very personal list of the ten greatest gesamtkunstwerk films of all time. Some of these films aren't necessarily "great" films, but they are beautiful examples of the magic that results when a director exploits to the full all the artistic elements at his disposal. I've excluded the trio of Kubrick, Fellini and Hitchcock from my list because they'd fill it up completely. Some of the films I've reviewed previously; just click on the titles to go to my full reviews.

Billion Dollar Brain (1967)

This was director Ken Russell's first feature film, and he must have decided to make a lasting impression in case it was also his last. There isn't a moment in the film that doesn't startle or amaze you with its style, wit and artistry. Special mention has to go to the theme music by Richard Rodney Bennet, and especially the cinematography which makes winter come alive like no other film has ever done.

The Godfather (1972)

This has to be most restrained gesamtkunstwerk film on this list. The brilliant script and acting is what draws your primary attention, but the set decoration and costuming is equally superb. And Gordon Willis' rich, yet understated cinematography might the film's greatest, but least obvious, asset.

Boogie Nights (1997)

A lot of people tend to get distracted by the sex when talking about this film. Look past that and you find a film that absolutely nails the look and sound of the era is describes, as well as handling a large cast of characters with the dexterity and attention to detail of a novel.

The Train (1964)

Director John Frankenheimer does not get the respect he deserves. He made some of the best films of the 1960s (The Birdman of Alcatraz, The Manchurian Candidate), and Ronin (1998), the best car chase film of all time. The Train is a World War Two movie that delivers on the action front, but also has a uniquely gritty, noir look for a war film and a soundtrack that mixes music and train sounds to great effect.

The Horseman on the Roof (1995)

Starring Olivier Martiniez and Juliette Binoche, this period romantic drama set in the south of France during a cholera epidemic looks and feels like an extravagant 19th century novel. The novel it's based on was written in 1951 and is pretty crappy, but the film version fires on all the artistic cylinders. Never has cholera looked so romantic or enchanting.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

There's no western that looks or sounds better, but what isn't noticed very much is the film's playfully religious sub-text, which I expound upon at some length in my full review.

Il Divo (2008)

If Sergio Leone had decided to do a political docudrama this is what it might have looked like. The subject is Giulio Andreotti, Italy's seven-time prime minister. What could have been a dry story is turned into a feast for the senses, highlighted by Toni Servillo's performance as Andreotti.

L'appartement (1996)

I said I wouldn't include any Hitchcock films on this list so instead I've cheated and chosen this French film that might just as well have been made by the master. The plot is a twistier version of Vertigo, the music is appropriately Bernard Herrmann-esque, and it stars Monica Bellucci, who makes virtually any film a gesamtkunstwerk.

The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968)

Trust the British to make an epic film out of one of their epic military disasters. This is a factual look at the infamous cavalry charge during the Crimean War, and the all-star British cast eats up the widescreen scenery. This has to also be the only historical epic to incorporate Terry Gilliam-like animated sequences.

The Best of Youth (2003)

This is the most conventional-looking of the films on this list, but it earns its place because it does such a remarkable job of taking a sprawling family saga and folding it seamlessly into the post-war history of Italy. Amazingly, this was first made for Italy's national broadcaster, RAI, but was deemed too good for TV and ended up in very limited theatrical release. It's six hours long and you'll wish it was twice as long.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)