The sub-genre of folk horror films is a tidy one, which is to say it's pretty small. Scurry around the Internet and you'll find various lists of folk horror films, the most prominent titles being The Wicker Man (1973), The Witch (2015) and Witchfinder General (1968). A handful of other titles appear on these lists, and the common denominators are that the tales are often set in the past, invariably in the countryside, and the action usually takes place somewhere in the British Isles. As a genre, it has the usual mix of duds, just-ok's, and hey-that-wasn't-bads. The Witch is actually a horror classic, folk or otherwise. I've always thought The Wicker Man was wildly overrated. Like a lot of genre films from the early '70s, it's perhaps more interested in women getting their clothes off than it is horror. And it isn't the least bit frightening. Witchfinder General doesn't even have nudity to recommend it. It's just deadly dull.

The Blood on Satan's Claw is a slightly better than average example of folk horror. On the negative side, it's plot doesn't stand up to the most minor scrutiny. An 18th century English peasant plows up a skull that has an eye glaring out it, and this somehow causes the local youths (and a few adults) to become Satan worshippers. The causality is murky, to say the least. Characters appear and disappear without explanation, there are continuity hiccups, and the finale is a bit of a damp squib.

What the film does have going for it is a genuinely eerie atmosphere.This is accomplished thanks to some first-rate cinematography that's very unusual for films of this genre and era. The English countryside is alternatively gorgeous and menacing, and its 18th century setting is made convincing with good locations and production design. The musical score is the equal the cinematography, which is perhaps even more unusual. Scores for low-budget horror films have a sorry habit of being as literal as the music in Bugs Bunny cartoons. All in all it's a fun film to watch unless you're a stickler for plot coherence, or are either disappointed or offended by the amount (minimal) of gratuitous female nudity on offer. And it's certainly more imaginative and well-crafted than those lame-ass found footage horror films that clutter up multiplexes on a regular basis.

Friday, July 28, 2017

Saturday, July 22, 2017

Film Review: Dunkirk (2017)

Christopher Nolan, the director of Dunkirk, is noted for wearing a suit and tie at all times while on the set of his films. His peers, on the other hand, usually favour baseball caps, jeans and T-shirts. The stiff formality of Nolan's wardrobe is also an expression of his directing style--neat, controlled, and featuring clean lines. And with Dunkirk he's fashioned a tailor's dummy of a film: rigid, inert, lifeless, and bearing only a vague similarity to reality.

Let's begin with the look of the film. This is the tidiest war film ever. The thousands of men on the beach at Dunkirk, who have spent the last few weeks in panicky flight from the Germans, are all wearing clean, well-fitted uniforms. Everyone is clean-shaven. The beach is pristine, with not a piece of debris in sight. The boats that ferry the soldiers off the beach are equally faultless. No wonder the British were pushed back to the sea so easily; they were battling an obsessive-compulsive cleaning disorder instead of the Germans. There have been many different kinds of war films, but never one that willfully ignores the fact that war is messy, dirty, bloody and unruly. I knew there was trouble ahead during the first scene in the film when we see a French street barricaded with sandbags. The barricade is so clean, so artfully arranged, it looks like the window display of a shop that sells designer sandbags--Sacs de Sable by Lagerfeld. It's true that the evacuation of Dunkirk took place in a relatively orderly fashion, but the neat queues of soldiers in this film belong on a parade ground, not a battlefield. Here's a picture of the real thing to illustrate my point:

And here's Nolan's version:

Normally I bemoan all the CGI in contemporary action films, but in this case I'll make an exception. At one point a character says that there are 400k soldiers on the beach. Really? I'm not sure that we see more than four thousand. Wasaga Beach on a Saturday in July looks busier than this. Nolan hates using CGI, but here it's hurt him. CGI could have filled the beach with men and debris, scrubbed out some modern-looking buildings along the beachfront, and filled the skies with more than a handful of warplanes. The evacuation of Dunkirk was a massive event in scope and scale, but Nolan has made it look like a minor skirmish.

CGI would not have helped with the script. The story follows the travails of about a dozen different Brits in three different plot lines. Most of them are unnamed, they have very little dialogue, and all of them are ciphers. It's difficult to invest emotion and attention in a story when the characters are just so many anonymous pawns. The script is clever in the way it jumps back and forth in time to bring all of the main characters together at the climax of the film, but the paths they take to get there are sometimes wonky. A trio of soldiers find a beached boat in the middle of nowhere (there was no middle of nowhere at Dunkirk, but never mind) and float in it out to sea just in time for the grand finale. It's a contrived bit of business and hardly represents the experience of the average soldier at Dunkirk. Even odder is a sequence on a rescue boat piloted by a civilian played by Mark Rylance. A sailor he pulls from the Channel (spoiler ahead!) accidentally knocks a teenage boy down the boat's steps. The boy bangs his head and dies. WTF is the point of this? This episode is so odd and pointless it ends up having no emotional impact.

Without getting all nerdy about the Second World War, I'll just say there are some real historical faux pas' on offer, but they pale in comparison to the other problems. Such as the soundtrack. I have the feeling Nolan saw the finished product, realized no one would be emotionally invested in the film, and tried to ramp up the energy and emotion by having a musical score that just won't shut up. The bombastic ear-bashing is continuous and tiresome. At times it sounds like the British are escaping an earthquake or volcano rather than Germans. And just in case we don't understand that time is running out for the British, the soundtrack handily includes a ticking clock for almost the entire length of the film. Really. I'm not making it up.

Dunkirk isn't a wretched film, but it's severely disappointing. A few early reviews I've read of it praise it for its technical achievements, which is, unfortunately, true. Nolan has done a good job as a technician, but a lousy job as an artist.

Let's begin with the look of the film. This is the tidiest war film ever. The thousands of men on the beach at Dunkirk, who have spent the last few weeks in panicky flight from the Germans, are all wearing clean, well-fitted uniforms. Everyone is clean-shaven. The beach is pristine, with not a piece of debris in sight. The boats that ferry the soldiers off the beach are equally faultless. No wonder the British were pushed back to the sea so easily; they were battling an obsessive-compulsive cleaning disorder instead of the Germans. There have been many different kinds of war films, but never one that willfully ignores the fact that war is messy, dirty, bloody and unruly. I knew there was trouble ahead during the first scene in the film when we see a French street barricaded with sandbags. The barricade is so clean, so artfully arranged, it looks like the window display of a shop that sells designer sandbags--Sacs de Sable by Lagerfeld. It's true that the evacuation of Dunkirk took place in a relatively orderly fashion, but the neat queues of soldiers in this film belong on a parade ground, not a battlefield. Here's a picture of the real thing to illustrate my point:

And here's Nolan's version:

Normally I bemoan all the CGI in contemporary action films, but in this case I'll make an exception. At one point a character says that there are 400k soldiers on the beach. Really? I'm not sure that we see more than four thousand. Wasaga Beach on a Saturday in July looks busier than this. Nolan hates using CGI, but here it's hurt him. CGI could have filled the beach with men and debris, scrubbed out some modern-looking buildings along the beachfront, and filled the skies with more than a handful of warplanes. The evacuation of Dunkirk was a massive event in scope and scale, but Nolan has made it look like a minor skirmish.

CGI would not have helped with the script. The story follows the travails of about a dozen different Brits in three different plot lines. Most of them are unnamed, they have very little dialogue, and all of them are ciphers. It's difficult to invest emotion and attention in a story when the characters are just so many anonymous pawns. The script is clever in the way it jumps back and forth in time to bring all of the main characters together at the climax of the film, but the paths they take to get there are sometimes wonky. A trio of soldiers find a beached boat in the middle of nowhere (there was no middle of nowhere at Dunkirk, but never mind) and float in it out to sea just in time for the grand finale. It's a contrived bit of business and hardly represents the experience of the average soldier at Dunkirk. Even odder is a sequence on a rescue boat piloted by a civilian played by Mark Rylance. A sailor he pulls from the Channel (spoiler ahead!) accidentally knocks a teenage boy down the boat's steps. The boy bangs his head and dies. WTF is the point of this? This episode is so odd and pointless it ends up having no emotional impact.

Without getting all nerdy about the Second World War, I'll just say there are some real historical faux pas' on offer, but they pale in comparison to the other problems. Such as the soundtrack. I have the feeling Nolan saw the finished product, realized no one would be emotionally invested in the film, and tried to ramp up the energy and emotion by having a musical score that just won't shut up. The bombastic ear-bashing is continuous and tiresome. At times it sounds like the British are escaping an earthquake or volcano rather than Germans. And just in case we don't understand that time is running out for the British, the soundtrack handily includes a ticking clock for almost the entire length of the film. Really. I'm not making it up.

Dunkirk isn't a wretched film, but it's severely disappointing. A few early reviews I've read of it praise it for its technical achievements, which is, unfortunately, true. Nolan has done a good job as a technician, but a lousy job as an artist.

Wednesday, July 19, 2017

Film Review: Get Out (2017)

One of the main strengths of Get Out is that it has the courage of its convictions. The genre is horror, but the subject is racism, and the film is unflinching in its portrayal of all the white characters as racists, albeit cosmetically liberal ones. In virtually every film about racism or prejudice, the script invariably includes a token character or two who goes against the racist grain. In this way we get war movies with a "decent" German or two, or westerns with cowboys who respect Indians. But because Get Out is a horror film, and horror films are formally about the stark, existential divide between good and evil, director/scriptwriter Jordan Peele can get away with having an all-nasty group of white characters. This works well for the horror and the comedy.

The plot is a recycling of The Stepford Wives from 1975, but please stifle the cries of plagiarism. The horror genre is full of poachers, and Ira Levin, who wrote the novel of The Stepford Wives, would later borrow the plot of Les Diaboliques (1955) for his play Deathtrap (1982). The protagonist is Chris, a young black photographer who travels with his white girlfriend to visit her parents, the Armitages, who live deep in the countryside. The parents are upper middle class, and the initial scenes in which they greet Chris and flaunt their liberal credentials ("I would've voted for Obama a third time!") are deliciously acute and cringeworthy. Daniel Kaluuya as Chris does a superb job of using subtle, non-verbal reactions to show us how risible, suspicious and clumsy white displays of "open-mindedness" sound to African American ears. In short order Chris realizes that the Armitages and their circle of friends have an intense and surgical interest in black people. The horror plot line that follows is done with understated style and great efficiency.

Get Out is funny, clever and tense, but what makes it special is its unique take on racism. It would have been easy to make the white characters KKK monsters of racism, but Peele does something much smarter. His black characters are exploited because the whites find aspects of blackness appealing or useful. The liberal racist, Peele seems to be saying, respects, even loves, blacks but only in certain strictly defined roles. The full-blown racist wants nothing to do with blacks, while the liberal racist finds aspects of blackness pleasantly exploitable (I did a fuller piece on this issue here). And racial issues aside, this is one of the most entertaining films I've seen this year.

The plot is a recycling of The Stepford Wives from 1975, but please stifle the cries of plagiarism. The horror genre is full of poachers, and Ira Levin, who wrote the novel of The Stepford Wives, would later borrow the plot of Les Diaboliques (1955) for his play Deathtrap (1982). The protagonist is Chris, a young black photographer who travels with his white girlfriend to visit her parents, the Armitages, who live deep in the countryside. The parents are upper middle class, and the initial scenes in which they greet Chris and flaunt their liberal credentials ("I would've voted for Obama a third time!") are deliciously acute and cringeworthy. Daniel Kaluuya as Chris does a superb job of using subtle, non-verbal reactions to show us how risible, suspicious and clumsy white displays of "open-mindedness" sound to African American ears. In short order Chris realizes that the Armitages and their circle of friends have an intense and surgical interest in black people. The horror plot line that follows is done with understated style and great efficiency.

Get Out is funny, clever and tense, but what makes it special is its unique take on racism. It would have been easy to make the white characters KKK monsters of racism, but Peele does something much smarter. His black characters are exploited because the whites find aspects of blackness appealing or useful. The liberal racist, Peele seems to be saying, respects, even loves, blacks but only in certain strictly defined roles. The full-blown racist wants nothing to do with blacks, while the liberal racist finds aspects of blackness pleasantly exploitable (I did a fuller piece on this issue here). And racial issues aside, this is one of the most entertaining films I've seen this year.

Wednesday, July 12, 2017

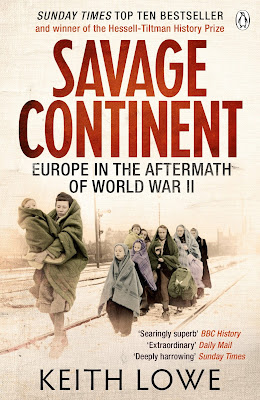

Book Review: Savage Continent (2012) by Keith Lowe

You would think by this point historians would have picked clean the carcass of the Second World War; every nook and cranny of the conflict, all it's minor and major characters have been the subject of histories or biographies. Case closed, right? Savage Continent proves otherwise. This history examines, in a brisk and brilliant manner, what happened in Europe after the end of hostilities, and reveals that vicious and bloody conflicts continued until about 1950.

The war ended at different times in different places. The Allies, for example, liberated southern Italy in 1943, and what became immediately apparent there (and would be true throughout Europe) was that once the Allied and Axis armies left the scene, the resulting military and political vacuum was rapidly filled with micro-conflicts. These ranged from peasants seizing vacant land in Italy to bloody ethnic cleansing in Poland and Yugoslavia. Tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of people died in these forgotten episodes, and many millions were displaced and driven from their homes and countries. Lowe shows that the end of the war often worked as an accelerant on long-standing hatreds and rivalries between political, ethnic and religious groups. The war had shown the utility of violence and pogroms, so in the chaos of the immediate aftermath of the war, when law and order and government had gone missing, something akin to mob rule took over large parts of Europe.

Savage Continent shines a light on many forgotten or neglected acts of cruelty and revenge. In Poland, genocidal ethnic cleansing took place between Polish and Ukrainian communities. Across eastern Europe the remnant Jewish population found that many people wanted to finish what the Germans had started. Ethnic Germans in the millions were forced out of this part of the continent, and all corners of Europe saw reprisals against those seen, rightly or wrongly, as collaborators. And on top of all this there were civil wars between communists and fascists in Greece and northern Italy.

One of the most important points Lowe makes is that in what became known as the Eastern Bloc, postwar ethnic cleansing produced countries that were virtually homogeneous in terms of ethnicity, religion and language. This helps explain how ethno-nationalist political parties have recently risen to the top in places like Hungary and Poland. Those countries were once relatively cosmopolitan, but now, after several generations of isolation, they have become intolerant and fearful of the free movement of people that's part and parcel of membership in the EU. All wars have an afterlife, but the Second World War may have the longest.

The war ended at different times in different places. The Allies, for example, liberated southern Italy in 1943, and what became immediately apparent there (and would be true throughout Europe) was that once the Allied and Axis armies left the scene, the resulting military and political vacuum was rapidly filled with micro-conflicts. These ranged from peasants seizing vacant land in Italy to bloody ethnic cleansing in Poland and Yugoslavia. Tens, perhaps hundreds, of thousands of people died in these forgotten episodes, and many millions were displaced and driven from their homes and countries. Lowe shows that the end of the war often worked as an accelerant on long-standing hatreds and rivalries between political, ethnic and religious groups. The war had shown the utility of violence and pogroms, so in the chaos of the immediate aftermath of the war, when law and order and government had gone missing, something akin to mob rule took over large parts of Europe.

Savage Continent shines a light on many forgotten or neglected acts of cruelty and revenge. In Poland, genocidal ethnic cleansing took place between Polish and Ukrainian communities. Across eastern Europe the remnant Jewish population found that many people wanted to finish what the Germans had started. Ethnic Germans in the millions were forced out of this part of the continent, and all corners of Europe saw reprisals against those seen, rightly or wrongly, as collaborators. And on top of all this there were civil wars between communists and fascists in Greece and northern Italy.

One of the most important points Lowe makes is that in what became known as the Eastern Bloc, postwar ethnic cleansing produced countries that were virtually homogeneous in terms of ethnicity, religion and language. This helps explain how ethno-nationalist political parties have recently risen to the top in places like Hungary and Poland. Those countries were once relatively cosmopolitan, but now, after several generations of isolation, they have become intolerant and fearful of the free movement of people that's part and parcel of membership in the EU. All wars have an afterlife, but the Second World War may have the longest.

Wednesday, July 5, 2017

Book Review: The Force (2017) by Don Winslow

Don Winslow's The Cartel (my review) was one of the best books I read in 2015. The Force is probably the worst I'll read this year. But it's a real page-turner if you like a fast-paced literary train wreck. I guess I stand guilty of hate-reading. The clue to why this novel is such a fall from grace is found in the author's acknowledgments at the end of the book. He thanks Ridley Scott and Twentieth-Century Fox for their interest in the manuscript and their purchase of the film rights "after our successful collaboration on The Cartel." There's the problem. The Force isn't a novel, it's a bloated, bombastic, nonsensical screenplay about crooked cops, ruthless crims and corrupt politicians. I'm guessing Winslow had both eyes on the future film as he wrote this and it completely ruined his work.

Denny Malone is the main character, a rock star detective working Manhattan North, making big busts with his four-man team. My money's on Tom Hardy to play him in the movie. Denny and his men are tarnished angels; they keep the streets clean but they also take bribes, kickbacks, and freebies. When they bust a drug dealer named Pena (Denny also executes him), they nab millions in cash and 50 kilos of high grade heroin. They see the loot as a retirement fund and college educations for their kids. They justify this kind of larceny because, well, everyone else does it and don't they deserve something for putting their lives on the line all the time? This crime proves to be Malone's undoing. In short order he's being targeted by Dominican gangsters, a Harlem drug lord, the Mafia, Internal Affairs, a federal task force, and some fellow cops. The Girl Guides also want him for skimming their cookie sales. Okay, it's a cheap joke, but that's the sort of response the novel demands. The plot gets progressively sillier until it climaxes with a city-wide race riot. But wait, there's more! Winslow dips into the lazy writer's toolbox and comes up with this old chestnut--a drawing room denouement! The meet is in a billionaire property developer's penthouse, and the guests include the mayor, the police commissioner, the billionaire, the DA, Malone, and Hercule Poirot various other top cops. Why are they there? So Malone can secretly record their incriminating conversations, of course. You've seen this trick in a hundred badly-plotted movies so be prepared to see it for the 101st time next year when the film comes out. And how could I forget Denny's schmaltzy redemption scene at the finale? Or the tedious info dumps that clog the first quarter of the novel? And of course there are all those superfluous scenes of our cop anti-heroes carousing and speaking fluent Toxic Masculinese.

Denny and his peers are a thinly drawn bunch who exist as amalgams of every macho cop cliche that's been around since Bullit. Denny even has a boss who tells him he won't put up with his team breaking the rules! And this is where a central problem with the novel becomes apparent: Winslow's imagination and inspiration are rooted in cop films from the 1970s. Most of the key characters are under the age of forty, but Winslow, who's in his early sixties, can't seem to bridge the generational divide. His characters sound and act out of time. He makes an awkward attempt to get with the times by having Denny love rap music, but it doesn't wash when he also has a woman sporting a "Veronica Lake-style hairdo" and a couple of other characters enjoying jazz music. Jazz? Jazz lovers are on the endangered species list and are kept in a special enclosure just outside New Orleans.

The novel's only apparent purpose or theme is to show that policing in New York is corrupt from top to bottom, not to mention racist and brutal. This was all said as long ago as 1972 in Across 110th Street with Yaphet Kotto and Anthony Quinn. And is this true of contemporary New York? N.Y.C. is statistically one of the safest big cities in America, but in Winslow's view it's a hellhole. Just imagine if he'd set his novel in Baltimore or Chicago. At a couple of points I thought the novel was going to make the link between the "War on Drugs" and the biblical levels of corruption, but it gets lost in a sea of turgid bromance, shouty and tone-deaf dialogue, and a romantic sub-plot between Denny and his black girlfriend that's only in place to assure us that, no, Denny isn't really racist. And Claudette, the girlfriend, gets to toss off a speech or two on race relations that would fit snugly on the Opinions page of the New York Times.

Speaking of girlfriends, in The Cartel Winslow's only real misstep was reflexively describing female characters in terms of their sexual desirability. He's worse here. Virtually every woman in the novel is some degree of "hottie." The nadir is reached when an irrelevant restaurant hostess is described as being "beyond beautiful." Beyond? Is she an immortal?

Like last year's film The Nice Guys with Russell Crowe and Ryan Gosling, The Force is a pained and clumsy exercise in '70s nostalgia. I'd even say he's poached bits and pieces from various '70s cop films. I keep comparing The Force to various films because as I said at the beginning it's not really a novel. It's a film treatment that needs to be pruned down, sharpened and given several coats of polish by a phalanx of script doctors. And that's probably exactly what will happen to it before it hits the local multiplex. By all means read The Cartel, which is a fantastic novel, but give this a pass and hope that the film version bombs so that Winslow can go back to writing novels. And if you want a fix of urban blight and crime, read Ghettoside: a True Story of Murder in America (2015) by Jill Leovy. It's a brilliant ground-level study of what the War on Drugs has done to African Americans in Los Angeles.

Denny and his peers are a thinly drawn bunch who exist as amalgams of every macho cop cliche that's been around since Bullit. Denny even has a boss who tells him he won't put up with his team breaking the rules! And this is where a central problem with the novel becomes apparent: Winslow's imagination and inspiration are rooted in cop films from the 1970s. Most of the key characters are under the age of forty, but Winslow, who's in his early sixties, can't seem to bridge the generational divide. His characters sound and act out of time. He makes an awkward attempt to get with the times by having Denny love rap music, but it doesn't wash when he also has a woman sporting a "Veronica Lake-style hairdo" and a couple of other characters enjoying jazz music. Jazz? Jazz lovers are on the endangered species list and are kept in a special enclosure just outside New Orleans.

The novel's only apparent purpose or theme is to show that policing in New York is corrupt from top to bottom, not to mention racist and brutal. This was all said as long ago as 1972 in Across 110th Street with Yaphet Kotto and Anthony Quinn. And is this true of contemporary New York? N.Y.C. is statistically one of the safest big cities in America, but in Winslow's view it's a hellhole. Just imagine if he'd set his novel in Baltimore or Chicago. At a couple of points I thought the novel was going to make the link between the "War on Drugs" and the biblical levels of corruption, but it gets lost in a sea of turgid bromance, shouty and tone-deaf dialogue, and a romantic sub-plot between Denny and his black girlfriend that's only in place to assure us that, no, Denny isn't really racist. And Claudette, the girlfriend, gets to toss off a speech or two on race relations that would fit snugly on the Opinions page of the New York Times.

Speaking of girlfriends, in The Cartel Winslow's only real misstep was reflexively describing female characters in terms of their sexual desirability. He's worse here. Virtually every woman in the novel is some degree of "hottie." The nadir is reached when an irrelevant restaurant hostess is described as being "beyond beautiful." Beyond? Is she an immortal?

Like last year's film The Nice Guys with Russell Crowe and Ryan Gosling, The Force is a pained and clumsy exercise in '70s nostalgia. I'd even say he's poached bits and pieces from various '70s cop films. I keep comparing The Force to various films because as I said at the beginning it's not really a novel. It's a film treatment that needs to be pruned down, sharpened and given several coats of polish by a phalanx of script doctors. And that's probably exactly what will happen to it before it hits the local multiplex. By all means read The Cartel, which is a fantastic novel, but give this a pass and hope that the film version bombs so that Winslow can go back to writing novels. And if you want a fix of urban blight and crime, read Ghettoside: a True Story of Murder in America (2015) by Jill Leovy. It's a brilliant ground-level study of what the War on Drugs has done to African Americans in Los Angeles.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)