If at some point late in the evening of October 27 you noticed a sudden wind stirring the tree branches outside your house, that was the result of Toronto's population collectively releasing its breath after the defeat of Doug Ford in the mayoral election. The pollsters all predicted it, but even the faint chance that they might be wrong had the city on edge as though fearing an impending natural disaster. Doug and Rob Ford have been the two-headed kaiju of Toronto politics, but now that they've been sent back to Monster Island, it's time to look at some of the hard lessons Toronto's learned from the election.

Racism Works

Toronto's media scratched its head raw trying to figure out why Doug and Rob could consistently draw the support of up to a third of the electorate despite spouting a string of racial, ethnic and religious slurs. What seemed even stranger was that the Fords had solid support from Toronto's visible minorities. I think the media was trapped in the idea that prejudice is the exclusive preserve of whites. If you've spent any time in public service, or taken a lot of cab rides, you quickly learn that a segment of every race, ethnic group, and religion has a bad word for the other guy. When the Fords vocalized their prejudices they appealed to anyone who's worldview is filled with stereotypes and bigotry. A portion of our population, no matter what its racial or ethnic origin, saw in the Fords people who share their prejudiced view of the world.

An Election is Not a Policy Symposium

Full disclosure: I was an Olivia Chow supporter. It was clear several weeks before the election that Chow was going to finish a distant third, a remarkable failure on her part given that she began the year as an overwhelming favourite. So what happened? The first problem was that Chow has spent her political life in the cozy bourgeois-bohemian confines of wards and ridings in downtown Toronto. At the ward or riding level you can get elected by going door-to-door, speaking to community groups, and generally doing a lot of one-on-one political work. Trained in this environment, Chow thought that simply articulating her policies was a sensible campaign strategy. That's not what elections on the big stage are about. People want to vote for someone who exudes confidence, determination, empathy, and a certain single-mindedness. Chow didn't offer that. She came across as a well-meaning senior civil servant who was tasked with explaining rules and regulations to her juniors. She had to sell herself as a leader and she failed completely. What was worse was that Chow began to campaign defensively with a series of self-deprecating remarks about her accent, her speaking style, and her insistence on sticking to discussions of policy. Her supporters got in on the act and started muttering that criticism of Olivia's campaigning style was veiled sexism, that being aggressive and loud was a male view of how to run for office. That argument didn't wash. Kathleen Wynne just won a provincial election quite handily without being aggressive or shouty, and she had a lot of political baggage to overcome. The simple answer for Chow's failure was that she didn't understand that an election campaign is about selling yourself rather than putting forward an agenda, and she sent the message that she had little faith in what she was selling.

TV News and Talk Radio is an Enabler

Throughout the Ford saga, the Toronto Star and, to lesser extent, the Globe and Mail, have proven over and over again that print journalism matters. They broke story after story about the Fords' crimes and misdemeanors, but all their good work was almost undone by local TV news and talk radio. Most people get their news from TV, and they were ill-served by the local talking heads. TV news twists itself into knots trying to present "balanced" coverage, and that meant the Fords could get coverage of their staged media events without analysis or context. TV news relies on an older demographic, a group that also happens to be key Ford supporters, and it seems obvious that they went out of their way to avoid alienating their audience with critical Ford coverage. Talk radio skews even older, and stations like 1010 were right behind the Fords, up to and including giving them their own show. You could almost include the Toronto Sun newspaper as part of talk radio because their advocacy for the Fords was so blatant any claims they had to being a news organization became risible. They were propagandists, plain and simple.

The Canadian Disease

Call it Canadian politeness, but we don't seem able to call a spade a spade. The Fords spouted lies the way a volcano spews ash, but I don't think I ever heard Chow, Tory or a reporter interviewing a Ford call them liars. Lying is the oxygen on Planet Ford, and without it they didn't really have a campaign or even a platform. Chow and Tory had multiple opportunities in debates and speeches to point out this fact out but something--fear of sounding rude?--stopped them. And why couldn't one of them have drawn attention to the Globe's story that Doug Ford was once a hash dealer? It's hard to imagine an American or British politician being given a free pass on that accusation by his opponents, but that's what Ford and Chow did.

What's the Matter with Kansas?

That's the title of a book by Thomas Frank that attempted to explain why poor and working-class Americans in red states support the Republican Party, something that clearly goes against their economic interests. The same phenomenon took place in Toronto. The poor and working poor flocked to the Fords, a pair of millionaires who want to slash city services, and snubbed Chow, the theoretical socialist. I say theoretical because Chow worked hard to make people forget her NDP roots. Late in the campaign, as her poll numbers collapsed, she began to call herself a progressive, but it was too late. Ford's demographic should have been hers, but like too many Canadian leftists she decided to chase the middle-class and ended up on the outside looking in. The Fords appeals to the poor, which consisted entirely of meaningless photo ops, was monstrously hypocritical, but it worked because they were the only ones making specific appeals to that group; the working-class was rewarding the Fords for having the courtesy to pay some attention to them.

Cops and Capitalists United in Impotence

During Rob Ford's time in the mayor's office he committed multiple crimes, including drug possession, impaired driving, and child (his own) endangerment. The police were tailing Ford off and on for months, and were very likely aware of these crimes as they happened, and certainly knew about them once they hit the newspapers. They took no action, except for mumbling excuses about "ongoing investigations." The city's business leaders were silent about the buffoon savaging Toronto's reputation around the world. In fact, many people in the business community (take a bow, Toronto realtors) were happy to have a mayor who woke up every morning with the words "Tax cuts!" on his lips. Ford's mayoralty was a clear, cold lesson that political power, even if it's wielded by an idiot, provides a moral Teflon-coating, especially when the idiot is singing from the right-wing hymnbook.

John Tory is the new mayor, and while he's highly unlikely to go on a crack-fueled rampage (he seems like more of a milk and Graham crackers guy), he's conservative to the tips of his Bass loafers and just as likely as Rob to try and cut city services. He'll do it politely, but his CV suggests that politically he and Ford have everything in common except recreational drug use. Here endeth the lesson.

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Thursday, October 23, 2014

The Best Non-Horror Horror Films

Every October the internet is awash with suggestions for Halloween-themed movie watching. This isn't exactly one of those lists. Rundowns of the best horror movies have a year after year sameness to them due to the fact that the genre has been in a creative rut for a quite a few years. On the one hand you have Paranormal Activity and its dozens of clones, and on the other you have torture porn/slasher films that only exist to highlight the work of the prosthetics wing of the SFX department. So here's a list of films that provide the fear and existential dread of the best horror films, but without any supernatural content or masked men wielding knives/axes/garlic presses.

Onibaba (1964)

Set in a marsh in rural Japan, a woman and her widowed daughter-in-law make a living killing lone samurai who cross their path. They dump the bodies in a deep hole in the marsh and sell the armour and weapons they've stripped from the bodies. Things go awry when the young woman acquires a love interest and her mother-in-law finds a "demon" mask. This is a seriously creepy and atmospheric film thanks to some amazing cinematography that's reminiscent of Val Lewton's horror films.

Innocence (2004)

The girls who live and study in this French boarding school make their first arrival at the school in coffins in which they seem to have been sleeping. Things get weirder. The school is in a walled park and no one is allowed out. After a peculiar course of study the girls are sent...but, no, that would be a spoiler. Marion Cotillard is one of the teachers in this sumptuous-looking film, which creates tension and dread by not giving us any clues as to what's really happening.

Winter's Bone (2010)

Every minute of this dark crime drama is filled with dread. Jennifer Lawrence's character, Ree, has to prove that her father's dead, and to do that involves running a gauntlet of back country characters who'd probably regard Deliverance as a sitcom. The hills of rural Missouri are filled with crazed crackheads, meth dealers, and garden variety bug-eyed rednecks, all of whom Ree has to negotiate with or cower in terror from. It's a hair-raising film that's almost devoid of violence.

The Parallax View (1974)

One of the key tropes in most supernatural films is that ordinary things aren't necessarily what they appear to be; see that sweet-looking doll over there? Turn away for a second and suddenly it's got it's hands around your throat. This political conspiracy thriller about a shadowy corporation that assassinates US politicians works a bit like that. Warren Beatty is a journalist who starts uncovering the truth but faces danger and double-crosses every step of the way. Director Alan J. Pakula brings the same mood of paranoid spookiness to this film as he did to Klute and All the President's Men.

Wake In Fright (1971)

Yet another horror film trope is the character who keeps making terrible choices, such as taking midnight strolls in cemeteries, going into attics/basements to investigate odd noises, and admitting men into the house who introduce themselves by saying, "I'm Count...uh...Alucard. Yeah, that's it, Count Alucard!" The central character in this Aussie film (but directed by Canuck Ted Kotcheff) is an Englishman who has to spend one night in a godawful Outback town for a flight that will take him back to England and civilization. He then makes a series of bad decisions that land him in one horrible situation after another, all involving the very unappetizing locals. The film has a gritty, documentary feel, an unrelenting sense of impending doom, a big, brassy performance from Donald Pleasance, and cinema's only knife fight between a man and a kangaroo.

The Hill (1965)

A tried and tested horror film structure is to have our hero(es) battle/run from a seemingly invulnerable maniac killer or supernatural entity. In the last few minutes of the film the baddie is bloodily defeated and all is well...or is it? The Evil One inevitably leaps back to life and things end badly for everyone except the film's producers, who've thereby left the door open for sequels. The Hill is set in a British military prison in North Africa that holds deserters and shirkers and the like. The officers in charge of the camp are a collection of bullies and incompetents, and one of their prisoners is worked to death as part of a punishment detail. A few of the prisoners, led by Sean Connery's character, try and have the responsible officer brought to justice. It seems like an impossible fight, and just when it looks like they've won...This is probably Connery's best performance, and he's supported by an A-list cast of Brit character actors all of whom try and outshout and outact each other; it's like a thespian version of WWE.

Juliet of the Spirits (1965)

The title character, an upper-middle-class Roman housewife, finds out her husband is having an affair and has a nervous breakdown. Her breakdown takes the form of seeing visions, and this being a Fellini film, the visions are eye-popping celebrations of Technicolor, sound design, and visual imagination. Fellini isn't trying for scares or even dread, but some of his imagery, especially in the final section of the film, makes you realize that he could have made an amazing horror film.

So there you have it; seven "horror" films that are largely blood and viscera free. And if you absolutely have to have celebrate Halloween with a horror film, check out Lake Mungo, an Australian film that could almost make this list because it keeps its supernatural elements to an absolute minimum and becomes all the scarier because of it.

Onibaba (1964)

|

| It gets scarier than this. |

Innocence (2004)

|

| "This doesn't look like Hogwarts." |

Winter's Bone (2010)

|

| And they live in the good part of town. |

The Parallax View (1974)

|

| One of them gets down the quick way. |

Wake In Fright (1971)

|

| Watch out! He's reaching for his pouch! |

The Hill (1965)

|

| Harry Andrews isn't keen on Connery's moustache. |

Juliet of the Spirits (1965)

|

| I'm telling you it's not a horror movie! |

So there you have it; seven "horror" films that are largely blood and viscera free. And if you absolutely have to have celebrate Halloween with a horror film, check out Lake Mungo, an Australian film that could almost make this list because it keeps its supernatural elements to an absolute minimum and becomes all the scarier because of it.

Thursday, October 16, 2014

Book Review: Get Carter (1970) by Ted Lewis

Get Carter is hands down the most iconic British gangster film of all time, and it's arguably the most memorable role of Michael Caine's career. It's odd, then, that it took so long for a publisher to reissue the novel it was based on. The original novel was called Jack's Return Home, which is an accurate, if underwhelming, description of the contents therein. And now the eternal question: which is better, the book or the film? The answer is that this one of the rare cases where the book and film are equally superb.

For the few people unfamiliar with the film or the book, the story follows London hood Jack Carter as he returns to his hometown, an industrial town in the north of England, for the funeral of his brother Frank. Jack suspects that Frank's death in a car crash wasn't accidental, and he's soon putting the hurt on various people to try and find out the truth. The local gangsters and Jack's bosses in London don't like that Jack is ruffling feathers and breaking heads, and decide it would be better if he was dead.

The novel has not aged one bit. The plot is tight and tense, but what really stands out is Lewis' dyspeptic prose. Here's his description of the patrons at a pretentious club/casino:

Inside, the decor was pure British B-feature except with better lighting. The clientele thought they were select. They were farmers, garage proprietors, owners of chains of cafes, electrical contractors, builders, quarry owners; the new Gentry. And occasionally, thought never with them, their terrible off-spring. The Sprite drivers with the accents not quite right, but ten times more like it than their parents, with their suede boots and their houndstooth jackets and their ex-grammar school girlfriends from the semi-detached trying for the accent, indulging in a bit of finger pie on Saturdays after the halves of pressure beer at the Old Black Swan, in the hope that the finger pie will accelerate the dreams of the Rover for him and the mini for her and the modern bungalow, a farmhouse style place, not too far from the Leeds Motorway for the Friday shopping.

Throughout the novel Lewis applies an acid wash to English society; more specifically, the culture and environment of ugly, money-obsessed, industrial towns in the North. Sometimes the novel reads like hate literature about northern England, but certain other (brief) passages are tinged with Jack's nostalgia for childhood outings with his brother in the countryside around the town. There's a sense in the novel that a more civilized, less mean-spirited England once existed but has now been consumed by a cabal of gangsters, bent coppers, avaricious politicians, and a middle-class obsessed with climbing the social ladder. The spirit of this older, better England is personified by Jack's brother. Frank is dead when the novel begins, but in a brilliant bit of writing Lewis lets us know all about him with a description of the contents of his living room bookcase; his tastes in magazines, books and music are an eloquent testimony to a sober, decent character who was too good and too old-fashioned for his place and time. As Jack investigates Frank's death it becomes even more clear that he was the odd man out in a town given over to self-interest and viciousness, and Jack's attempt to solve and avenge Frank's murder becomes an attempt to reclaim some small part of the innocence he once shared with his brother.

The literary step-parents of Get Carter are Alan Sillitoe and Harold Pinter. Jack's misanthropic descriptions of the town are an echo of the anger Sillitoe brought to his novels and short stories set in the north. Sillitoe had more sympathy for his characters, trapped as they were in dead end jobs and dreary housing estates, and he was more concerned with showing the social and political facts that produced depressed lives and dreary communities. Get Carter's terse, elliptical, and allusive dialogue is pure Pinter. Jack's chats with his fellow gangsters usually have a neutral and pleasant tone but underneath it all they're straining to express violence, rage and naked threats. It's a unique way to create tension, and it's a device that was developed further by Brit crime writer Bill James in his long-running Harpur & Iles series.

So, how far does the book differ from the film, you ask? Not that much, really. The plot was streamlined for the film, and scriptwriter/director Mike Hodges did a wonderful job of choosing what to cut and compress. In a few places the film actually does a better job than the novel; Jack's famous line in the film when he meets Cliff Brumby ("You're a big man, but you're in bad shape. With me it's a full time job. Now behave yourself") is a tweaked improvement over the dialogue from the book. Hodges also made a wise decision to tone down some of the violence aimed at the female characters. Ted Lewis wrote two other Jack Carter novels, Jack Carter's Law and Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon, both of which are also being reissued.

For the few people unfamiliar with the film or the book, the story follows London hood Jack Carter as he returns to his hometown, an industrial town in the north of England, for the funeral of his brother Frank. Jack suspects that Frank's death in a car crash wasn't accidental, and he's soon putting the hurt on various people to try and find out the truth. The local gangsters and Jack's bosses in London don't like that Jack is ruffling feathers and breaking heads, and decide it would be better if he was dead.

The novel has not aged one bit. The plot is tight and tense, but what really stands out is Lewis' dyspeptic prose. Here's his description of the patrons at a pretentious club/casino:

Inside, the decor was pure British B-feature except with better lighting. The clientele thought they were select. They were farmers, garage proprietors, owners of chains of cafes, electrical contractors, builders, quarry owners; the new Gentry. And occasionally, thought never with them, their terrible off-spring. The Sprite drivers with the accents not quite right, but ten times more like it than their parents, with their suede boots and their houndstooth jackets and their ex-grammar school girlfriends from the semi-detached trying for the accent, indulging in a bit of finger pie on Saturdays after the halves of pressure beer at the Old Black Swan, in the hope that the finger pie will accelerate the dreams of the Rover for him and the mini for her and the modern bungalow, a farmhouse style place, not too far from the Leeds Motorway for the Friday shopping.

Throughout the novel Lewis applies an acid wash to English society; more specifically, the culture and environment of ugly, money-obsessed, industrial towns in the North. Sometimes the novel reads like hate literature about northern England, but certain other (brief) passages are tinged with Jack's nostalgia for childhood outings with his brother in the countryside around the town. There's a sense in the novel that a more civilized, less mean-spirited England once existed but has now been consumed by a cabal of gangsters, bent coppers, avaricious politicians, and a middle-class obsessed with climbing the social ladder. The spirit of this older, better England is personified by Jack's brother. Frank is dead when the novel begins, but in a brilliant bit of writing Lewis lets us know all about him with a description of the contents of his living room bookcase; his tastes in magazines, books and music are an eloquent testimony to a sober, decent character who was too good and too old-fashioned for his place and time. As Jack investigates Frank's death it becomes even more clear that he was the odd man out in a town given over to self-interest and viciousness, and Jack's attempt to solve and avenge Frank's murder becomes an attempt to reclaim some small part of the innocence he once shared with his brother.

The literary step-parents of Get Carter are Alan Sillitoe and Harold Pinter. Jack's misanthropic descriptions of the town are an echo of the anger Sillitoe brought to his novels and short stories set in the north. Sillitoe had more sympathy for his characters, trapped as they were in dead end jobs and dreary housing estates, and he was more concerned with showing the social and political facts that produced depressed lives and dreary communities. Get Carter's terse, elliptical, and allusive dialogue is pure Pinter. Jack's chats with his fellow gangsters usually have a neutral and pleasant tone but underneath it all they're straining to express violence, rage and naked threats. It's a unique way to create tension, and it's a device that was developed further by Brit crime writer Bill James in his long-running Harpur & Iles series.

So, how far does the book differ from the film, you ask? Not that much, really. The plot was streamlined for the film, and scriptwriter/director Mike Hodges did a wonderful job of choosing what to cut and compress. In a few places the film actually does a better job than the novel; Jack's famous line in the film when he meets Cliff Brumby ("You're a big man, but you're in bad shape. With me it's a full time job. Now behave yourself") is a tweaked improvement over the dialogue from the book. Hodges also made a wise decision to tone down some of the violence aimed at the female characters. Ted Lewis wrote two other Jack Carter novels, Jack Carter's Law and Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon, both of which are also being reissued.

Saturday, October 11, 2014

Book Review: Alone in Berlin (1947) by Hans Fallada

Well, the contest is officially over. George Orwell's 1984 and Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon have been relegated to my personal second division of searing novels about life in a brutal, totalitarian state. It wasn't even close. The prime reason for Alone in Berlin taking home the cup is that Hans Fallada knew whereof he spoke. In 1911, at the age of eighteen, Fallada killed his best friend as part of a mutual suicide pact and then bungled his own attempt to kill himself. Life was telling Fallada something. He was then banged up in a psychiatric hospital, and for the rest of his life (he died shortly after finishing this novel) Fallada was in and out of prisons, hospitals and psych wards. He battled addictions to drugs and booze, worked as a farmer and journalist, and eventually became one of the more successful and well-known German writers of the 1930s. One of his novels, What Now, Little Man?, was even made into a successful Hollywood movie in 1934. Under the Nazis he alternately resisted and knuckled under (Goebbels put a menacing word in his ear) to their insistence that his writings take a pro-Nazi stance. Fallada had intimate knowledge of resistance and collaboration, and those are the twin poles around which his last novel revolves.

Alone in Berlin is based on a true story and follows Otto and Anna Quangel, a working-class couple whose only child, a son, is killed in action in 1940. They're devastated, but unlike millions of other Germans, the couple decide to clandestinely protest the war. They start writing anti-war, anti-Hitler statements on postcards and drop them in public places. The Gestapo is soon on the case, although the impact of their protest is clearly negligible. The Quangels manage to evade capture for several years, but, inevitably, luck turns against them and they're caught, and the last quarter of the novel covers their interrogation, trial and imprisonment.

The Quangels are at the centre of the story, but there are at least a dozen other characters who orbit around them, including co-workers, neighbours, relatives, cops, Gestapo officers, and criminals. These supporting characters include (to name a few) ardent and avaricious Nazis; working-class Berliners trying to keep their heads down and endure the war; petty criminals who are both evading and profiting from the war; and naive, hopeless resisters to the Nazis. Fallada knew what life was like in the lower reaches of German society, and presents it with a brutal, even enthusiastic, harshness. His characters are terrified of the Nazis and the war, and the horror of the regime seems to bleed into personal relationships, many of which are violent and toxic. Fallada is brilliant at describing the petty, degrading horrors of life under Nazidom and the way people will demean themselves to stay out of trouble or curry favour with the authorities. The prison sections of the story are the best of their kind I've ever read. Fallada had many and varied experiences of being detained by the state, and every morsel of that experience and knowledge makes it into the novel.

Grim would be a good, catchall description of Alone in Berlin, but it's also ferociously tense and spiked with a terrifically black sense of humour. It makes for an odd but exhilarating reading experience. There are no happy endings for anyone, but Fallada writes with such energy and descriptive richness that reading about the horrors of life under the Nazis becomes perversely pleasurable. What's even more remarkable about this novel is that Fallada wrote it in under a month, and you can sense that he was in a rush to capture in prose all the rage, bitter sarcasm, and cynical humour that had been bottled up inside him since the Nazis came to power. Alone in Berlin isn't just a great novel about totalitarianism, I'd also put it forward as perhaps the best novel to come out of World War Two.

Alone in Berlin is based on a true story and follows Otto and Anna Quangel, a working-class couple whose only child, a son, is killed in action in 1940. They're devastated, but unlike millions of other Germans, the couple decide to clandestinely protest the war. They start writing anti-war, anti-Hitler statements on postcards and drop them in public places. The Gestapo is soon on the case, although the impact of their protest is clearly negligible. The Quangels manage to evade capture for several years, but, inevitably, luck turns against them and they're caught, and the last quarter of the novel covers their interrogation, trial and imprisonment.

The Quangels are at the centre of the story, but there are at least a dozen other characters who orbit around them, including co-workers, neighbours, relatives, cops, Gestapo officers, and criminals. These supporting characters include (to name a few) ardent and avaricious Nazis; working-class Berliners trying to keep their heads down and endure the war; petty criminals who are both evading and profiting from the war; and naive, hopeless resisters to the Nazis. Fallada knew what life was like in the lower reaches of German society, and presents it with a brutal, even enthusiastic, harshness. His characters are terrified of the Nazis and the war, and the horror of the regime seems to bleed into personal relationships, many of which are violent and toxic. Fallada is brilliant at describing the petty, degrading horrors of life under Nazidom and the way people will demean themselves to stay out of trouble or curry favour with the authorities. The prison sections of the story are the best of their kind I've ever read. Fallada had many and varied experiences of being detained by the state, and every morsel of that experience and knowledge makes it into the novel.

Grim would be a good, catchall description of Alone in Berlin, but it's also ferociously tense and spiked with a terrifically black sense of humour. It makes for an odd but exhilarating reading experience. There are no happy endings for anyone, but Fallada writes with such energy and descriptive richness that reading about the horrors of life under the Nazis becomes perversely pleasurable. What's even more remarkable about this novel is that Fallada wrote it in under a month, and you can sense that he was in a rush to capture in prose all the rage, bitter sarcasm, and cynical humour that had been bottled up inside him since the Nazis came to power. Alone in Berlin isn't just a great novel about totalitarianism, I'd also put it forward as perhaps the best novel to come out of World War Two.

Tuesday, October 7, 2014

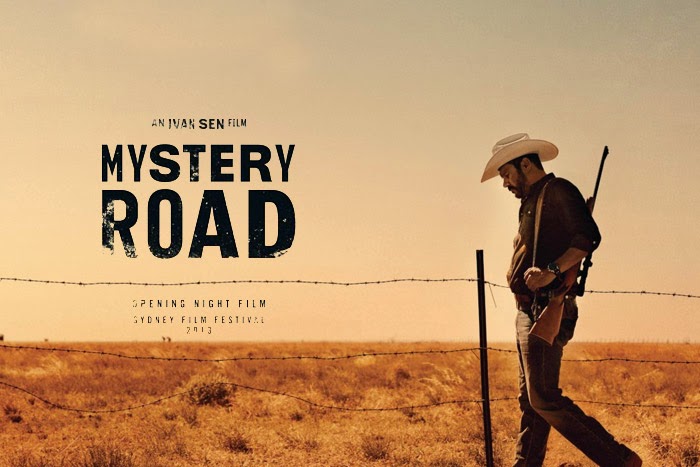

Film Review: Mystery Road (2013)

There are lots of things to like about the look of this Australian mystery-thriller, but the strong visual elements paper over a threadbare plot and characters who seem to have been developed on an Etch-A-Sketch. The story takes place in a small community in one of the most Outbacky-looking parts of the Outback, and that means we're treated to a full share of limitless vistas, glorious sunrises and sunsets, and shots of people dwarfed by desiccated, yet epic, landscapes. That's all well and good, but the Outback, like the Alps or the Hawaiian Islands, is one of nature's visual wonders, and any half-decent cinematographer should be able to find some eye candy in those locations.

The mystery at the heart of Mystery Road is the murder of an aboriginal girl just outside of town beside a highway used by big-rig truckers. The investigating detective is Jay Swan, part aborigine, and recently returned to his hometown from a stint working in the big city. If Jay had seen his share of mysteries set in small towns in which outsider cops figure, he'd have been prepared for the cold shoulder he receives from all and sundry. He's disliked and distrusted by the all-white police force, and equally scorned by the local aborigines because he's working for the white authorities. Oh no, he's a man caught between two cultures! This aspect of film isn't done with any originality, except in the visual realm. Jay's dealings with these two communities are filled with a palpable physical tension. The people he talks to and/or questions lean away from him, look to one side, or otherwise convey through their movements and posture their utter disdain for Jay. It's a smart and visual way to convey information without resorting to dialogue.

The weakest part of the film is the mystery. Striking shots of the Outback don't make up for a plot that wanders off in various directions at a very slow pace, and then leaves us almost completely in the dark as to what happened to whom and why. Fortunately, the film ends with one absolutely terrific action sequence that plays out over vast distances. An added bonus is the work of actor Aaron Pedersen in the role of Jay Swan. He has a strong, Russell Crowe-like physical presence that makes him the centre of visual attention even if he's just standing or sitting.

The mystery at the heart of Mystery Road is the murder of an aboriginal girl just outside of town beside a highway used by big-rig truckers. The investigating detective is Jay Swan, part aborigine, and recently returned to his hometown from a stint working in the big city. If Jay had seen his share of mysteries set in small towns in which outsider cops figure, he'd have been prepared for the cold shoulder he receives from all and sundry. He's disliked and distrusted by the all-white police force, and equally scorned by the local aborigines because he's working for the white authorities. Oh no, he's a man caught between two cultures! This aspect of film isn't done with any originality, except in the visual realm. Jay's dealings with these two communities are filled with a palpable physical tension. The people he talks to and/or questions lean away from him, look to one side, or otherwise convey through their movements and posture their utter disdain for Jay. It's a smart and visual way to convey information without resorting to dialogue.

The weakest part of the film is the mystery. Striking shots of the Outback don't make up for a plot that wanders off in various directions at a very slow pace, and then leaves us almost completely in the dark as to what happened to whom and why. Fortunately, the film ends with one absolutely terrific action sequence that plays out over vast distances. An added bonus is the work of actor Aaron Pedersen in the role of Jay Swan. He has a strong, Russell Crowe-like physical presence that makes him the centre of visual attention even if he's just standing or sitting.

Thursday, October 2, 2014

Book Review: The People in the Trees (2013) by Hanya Yanagihara

The utter brilliance of this novel can be gauged by the fact that its central character and narrator starts off as annoying and unlikable, and proceeds from there, by stages, to become despicable and utterly repellent, and yet it's impossible not to be fascinated by his train wreck of a character arc. Bad guys and girls can often be compelling fictional characters, but Norton Perina, the sociopathic scientist at the centre of the novel, lacks the glamour or calculating genius of a Hannibal Lecter or Blofeld. Perina is anti-social, pedantic, misogynistic, lacking in empathy, occasionally sadistic, and, worst of all, an enthusiastic pedophile. Yanagihara's compelling, incisive writing keeps us fascinated with Perina even though it's hard not to spend most of the novel hoping that he's bitten by a poisonous snake or run over by a bus or shot with a...you get the idea.

The novel is written as a series of autobiographical letters sent by Perina from his prison cell to a friend and fellow scientist. The friend feels that Perina's remarkable career demands some kind of autobiography. Perina is raised on a farm in Ohio in the 1930s by parents who are both one card shy of a full deck. He goes to medical college and in 1950 joins an expedition to a chain of barely-explored islands in Micronesia. Perina is accompanied by two anthropologists, and the purpose of the expedition is to make find a tribe that has never had contact with the outside world. The tribe is found and it seems they have discovered the key to extending life. Some of them appear to be hundreds of years old, but while their bodies don't age, their minds eventually turn to mush and they wander the jungle like animals. Perina's research, and his realization that eating a turtle found only on the island extends the islander's life, provide the foundation for his spectacular career in research, which culminates in the winning of a Nobel prize a decade or so later. The island is eventually despoiled by researchers and pharmaceutical companies searching the island for more medical marvels. The turtles quickly become extinct, and the key to longer life is never found. Perina makes many trips back to the island and starts adopting the island's abandoned children, forty-seven in total, and brings them back to the US where he raises them himself. Perina is arrested in the 1990s and charged with sexually assaulting one of his adopted children, and his final letter to his friend lays bare the enormity of his crimes.

The People in the Trees works superbly on many levels. It's an adventure story about exploration, an allegory about Western exploitation of Third World cultures and resources, a critique of scientific curiosity, and a clinically thorough examination of a brilliant sociopath. One theme in the novel could be described as the fascism of scientific inquiry. In Perina's career, and in the scientific/academic environment he lives in, the quest for empirical truths trumps all considerations of ethics and morality, and even common sense. One of the tragedies of Perina's life is that his amorality actually makes him a better scientist, and his resulting professional success makes him a more successful monster. The awfulness of Perina is made bearable and fascinating by Yanagihara's meticulous examination of his thoughts and beliefs. He's far from a one-dimensional villain; at times he can show pity, even affection, and he's even aware of the cruelty he's unleashed on the island. Perina's POV is always colored by his general misanthropy. This becomes particularly apparent during his first trip to the island when his descriptions of the flora and fauna are filled with disgust and loathing. Perina is surrounded by riotous tropical life, and its fecundity and variety seems to horrify him, possibly because he can't control or dominate this environment.

The psychological and physical horrors that fill this novel are made tolerable thanks to Yanagihara's lush, precise prose. She moves seamlessly from describing tribal life, the ecology of her imaginary jungle, to the intricacies of scientific research without missing a beat. It's an amazing achievement, albeit one that's sometimes hard to stomach.

The novel is written as a series of autobiographical letters sent by Perina from his prison cell to a friend and fellow scientist. The friend feels that Perina's remarkable career demands some kind of autobiography. Perina is raised on a farm in Ohio in the 1930s by parents who are both one card shy of a full deck. He goes to medical college and in 1950 joins an expedition to a chain of barely-explored islands in Micronesia. Perina is accompanied by two anthropologists, and the purpose of the expedition is to make find a tribe that has never had contact with the outside world. The tribe is found and it seems they have discovered the key to extending life. Some of them appear to be hundreds of years old, but while their bodies don't age, their minds eventually turn to mush and they wander the jungle like animals. Perina's research, and his realization that eating a turtle found only on the island extends the islander's life, provide the foundation for his spectacular career in research, which culminates in the winning of a Nobel prize a decade or so later. The island is eventually despoiled by researchers and pharmaceutical companies searching the island for more medical marvels. The turtles quickly become extinct, and the key to longer life is never found. Perina makes many trips back to the island and starts adopting the island's abandoned children, forty-seven in total, and brings them back to the US where he raises them himself. Perina is arrested in the 1990s and charged with sexually assaulting one of his adopted children, and his final letter to his friend lays bare the enormity of his crimes.

The People in the Trees works superbly on many levels. It's an adventure story about exploration, an allegory about Western exploitation of Third World cultures and resources, a critique of scientific curiosity, and a clinically thorough examination of a brilliant sociopath. One theme in the novel could be described as the fascism of scientific inquiry. In Perina's career, and in the scientific/academic environment he lives in, the quest for empirical truths trumps all considerations of ethics and morality, and even common sense. One of the tragedies of Perina's life is that his amorality actually makes him a better scientist, and his resulting professional success makes him a more successful monster. The awfulness of Perina is made bearable and fascinating by Yanagihara's meticulous examination of his thoughts and beliefs. He's far from a one-dimensional villain; at times he can show pity, even affection, and he's even aware of the cruelty he's unleashed on the island. Perina's POV is always colored by his general misanthropy. This becomes particularly apparent during his first trip to the island when his descriptions of the flora and fauna are filled with disgust and loathing. Perina is surrounded by riotous tropical life, and its fecundity and variety seems to horrify him, possibly because he can't control or dominate this environment.

The psychological and physical horrors that fill this novel are made tolerable thanks to Yanagihara's lush, precise prose. She moves seamlessly from describing tribal life, the ecology of her imaginary jungle, to the intricacies of scientific research without missing a beat. It's an amazing achievement, albeit one that's sometimes hard to stomach.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)